Sorbus buddleia, larix kaempferi and liriodendron tulipifera… Walking past the exotic plants of Edinburgh’s Botanic Gardens, I enter Inverleith House to reach Karla Black’s new exhibition titled Sculptures. From mounds of pastel powder to crumpled paper constructions and polythene hanging forms, Black’s abstract sculptures form a startling foil to the grand classical rooms. The first sculpture I encounter, Left Right, Left Right, has immediate and dramatic impact. At first it appears as if a pile of earth has been dropped into the gallery, bringing the Botanic Gardens indoors. This mass of soil, speckled with spray paint and powder, is barely contained by the large space it inhabits. Upon closer inspection, its seemingly haphazard form possesses carefully-composed edges and a delicately-patted down surface. The white pillars of Acceptance Changes Nothing similarly prompt a consideration of the work’s materiality. The scattered dust around its base suggests a composition of loose powder – how does it remain intact and upright? Black’s large-scale works edge into the corners of the room, obliging us to back up against walls and to carefully step around them so as not to disturb their fragile powder surfaces. By entering into a more physical relationship with the work than usual, in a gallery context, we are repositioned as participants rather than viewers.

Black works in situ, producing site-specific sculptures using impermanent materials such as toothpaste, vaseline and make-up. Ephemerality is not necessarily her aim. Instead, these substances are sought for “the energy, life and movement that they give.”[1] This deeply tactile exhibition, covered in drips, rips, rusts and stains, reveal a preoccupation with processes of pouring, mixing, melting and smearing. The surfaces produced invoke the body, often appearing skin-like. This is achieved through her so-called ‘domestic’ materials, those applied to or consumed by the body. For example, the pink fleshy tones of Concentrate On Capacity are rendered with cream foundation and concealer while pastel eyeshadow has been applied to the crumpled folds of Vanity Matters. Better, a floor-based sculpture, is a lumpy beige swirl laid out on the ground that consists of melted heartburn medication.[2]

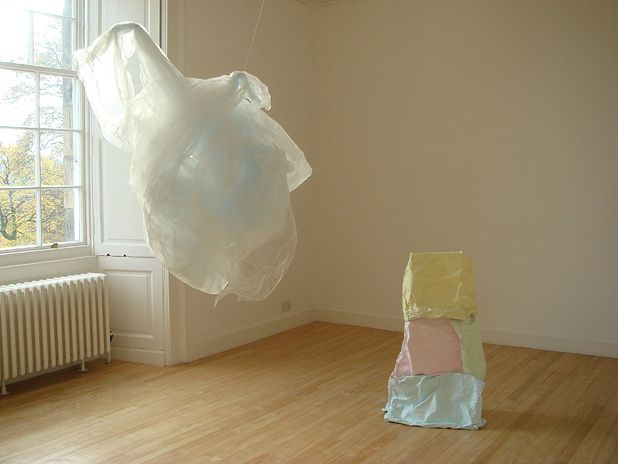

Black is skilled at moulding and stretching materials beyond their usual capacity. She entices the viewer to get up close and examine the surfaces which are never quite what they seem. The bunched green fabric corners of Demands Unfocus are in fact sheets of paper covered in green chalk. Sugar paper has been effortlessly rendered by the artist into a weighty fabric, suspended from the ceiling by four thin strings. It resembles a container used to lift heavy animals, although if one stretches to peek over its edges, it turns out to have no bottom. It’s Proof That Counts presents a barrier to be stepped around and scrutinised. The long wall appears to be a panel of melted metal. In fact, it is large sheet of brown paper daubed with white acrylic and coloured pink with chalk. Protective Edge transforms a polythene bag by delicately suspending it from the ceiling. It contains a cloud of yellow chalk dust. Works such as this impede our progress through the gallery and demand that we stop to consider them fully. This interest in process can be traced to Black’s earlier performance work which has since developed into installation. This action-oriented approach, however, remains in the work’s titles.

The artist has chosen to install landscapes by the Scottish painter Bet Low (1924-2007) alongside her work. Though these elemental depictions of the Orkney landscape are compelling, the connection to Black’s oeuvre only really becomes apparent upon reading the text that accompanies the exhibition. Selected by Black, this interview with Andrew Greig rhapsodises about the pleasure of becoming engulfed by the Orkney landscape to the point where one’s conscious self recedes:

“Gradually you move from the kind of conceptual realm we normally live in – this ghost in the head – into one’s physical being, which is the one part of me I really trust, or believe in, and with that physicality comes a presence you simply do not get otherwise, and that’s the present moment that I love.”[3]

This extract crystallises a central theme in Black’s work- a profound faith in corporeal as opposed to linguistically-conceived experience. Her sculptures offer an escape from self-consciousness by providing “an actual engulfment in the physical.”[4] In A Very Important Time for Handbags, she writes:

“I want to make abstract not figurative art; I want to prioritise material experience over language; I want formal aesthetics rather than a narrative, autobiographical detail; I want the lived life to be primary, not the looked-at image.” [5]

By filling the rooms, thus obstructing our way, her sculptures appeal to the body’s language and inspire an embodied response. Black incorporates feminist tropes into her work through the use of ‘domestic’ products, invoking the slogan that the personal must become the political. “The shocked, stopped, self-conscious life as ‘image’ distracts women from this physical connection with the world into focusing on how they look. Her tactile surfaces dispute the authority of the eye. The irony of all this, of course, is the universal gallery stipulation that art must be looked at from a distance and never touched. The very system within which Black operates reproduces the hierarchy of sight over touch. Yet, at the same time, she subverts the objecthood of her work through its ephemerality.[7]

Black’s practice works on the basis that material human experience precedes language as the most absorbent and unselfconscious way of understanding. Whilst Black professes an interest in Kleinian psychoanalysis, her work also recalls French feminist theory and writers such as Helene Cixous, Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray, who draw strongly upon Lacan’s writing. This strand of psychoanalysis draws a parallel between the child’s moment of adoption of language and the development of “I”, with self-consciousness or the recognition of the mirror-image.

“The moment we become aware of ourselves from the outside in, as an image that others can see, or as a subject that holds a particular meaning, symbolic or otherwise, then we split from that primary experience of the physical world and must think.”[8]

Calls for semiotic communication are critiqued on the basis that they perpetuate essentialism and, worse still, reduce female utterances (or in this case, artwork) to incoherency. Yet, the appeal to material experience is so radical that it involves a reconceptualising of the very structures within which we apprehend the world around us and, naturally enough, proves difficult to understand (not in itself a failing, it must be said). By eschewing imagery, Black’s work ultimately becomes part of the environment, rather than representing it. In doing so, it highlights how real objects and events are continually coopted and imagined as symbols. It serves to question why women’s artwork is judged to be gendered whereas this is rarely a consideration for male artists. In what kind of cultural climate do such interpretations persist?

Notes

[1]Karla Black in conversation with Lauren O’Neill-Butler, Artforum, October 2009.

[2]This last piece recalls her 2001 work ‘Untitled (2000 Alka-Seltzer in the Rain)’ and illustrates a consistent preoccupation with the body and its substance.

[3]Andrew Greig in conversation with John McCarthy, Excess Baggage, BBC Radio 4, 7th November, 2009.

[4]Karla Black in conversation with Lauren O’Neill-Butler, Artforum, October 2009.

[5]Karla Black, ‘A Very Important Time for Handbags’, Mistakes Made Away From Home, 2008.

[6]Ibid.

[7]The artist negotiates her institutional context and compromises by providing an object, but its temporary nature allows her inclinations to triumph: “The work is both a protest and a compromise at the same time. While it tries to dismantle the demands of being permanent, transferable, and stable, as required by most art institutions, it also physically and sculpturally renegotiates within those conditions and reaches compromises that allow it to exist in those places.” Karla Black in conversation with Lauren O’Neill-Butler, Artforum, October 2009.

[8]Ibid.

Ciara Moloney is a writer who lives in Dublin.