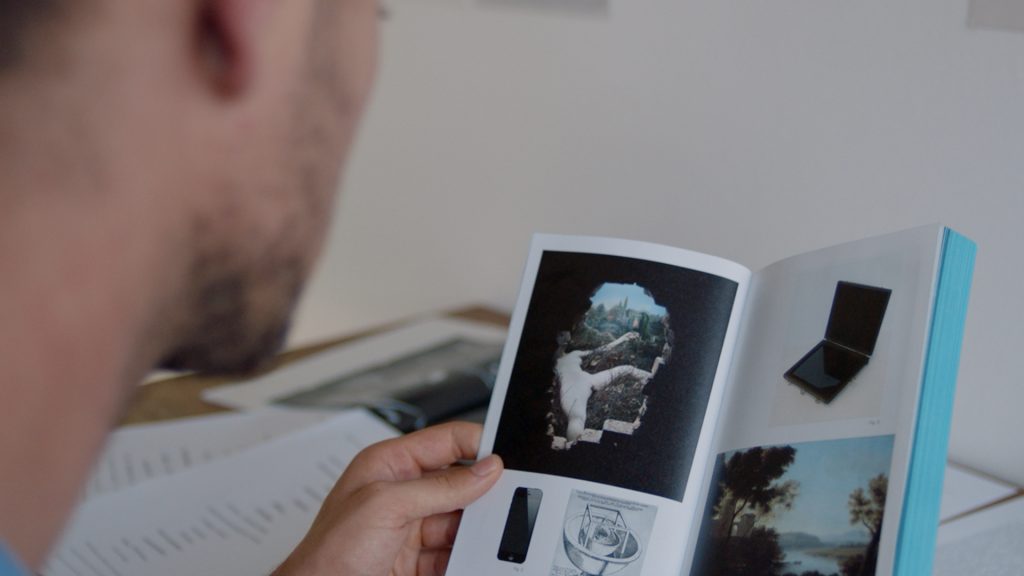

‘He who sees is a cunt,’ Jean-François Lyotard remarked on observing Marcel Duchamp’s voyeuristic Étant donnés (1946–66).[1] In Duchamp’s enigmatic work, recalling Gustave Courbet’s L’origine du monde (1866), the viewer assumes the role of a Peeping Tom who is confronted with a partial view, framed by a hole in a brick wall, of a nude female figure, her vulva meeting the perspectival line of the viewer’s gaze. A reproduction of Étant donnés appears more than once in Doireann O’Malley’s Prototypes I and II. As a visual leitmotif, it serves as a reminder that looking – and the act of representation – is never neutral. Our gaze, like a loaded gun, is marked by sexual difference. Jacques Lacan referred to this as a ‘central lack that is expressed in the phenomenon of castration’.[2]

Doireann O’Malley

Still from Prototypes I: Quantum Leaps in Trans Semiotics through Psycho-Analytical Snail Serum, 2017

Three-screen film installation, 33 minutes

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, 22 June–14 October 2018

Courtesy of the artist

In terms of both production and critical reception, it is difficult to overestimate the relationship between visual culture and psychoanalysis during the twentieth century. [3] Michel Foucault argued in The Order of Things (1966) that the modern subject that emerged during the nineteenth century differed from the classical subject of Cartesian and Kantian philosophies ‘because he seeks his truth in the un-thought – the unconscious and the other’,[4] or what anthropologists termed the ‘primitive’. The systematic development of ethnic and medical categories to justify the nineteenth-century colonial project coincided with the development of psychoanalysis and anthropology. These two sciences did more than most to buttress the subjectivity of the white European via neat linguistic operations such as ethnic or sexual othering or the shoring up of gender binaries. They effectively categorised and pathologised anyone who did not correspond to the conventional image of those in power.

Prototypes addresses this history obliquely from the perspective of those transgender and non-binary bodies that have been the subject of psychoanalysis’ pathologising function of othering. Installed in two separate rooms as a diptych and triptych presentation respectively, Prototypes is an immersive experience featuring sweeping cinematographic shots of Berlin’s bold modernist architecture alongside endless parks and pristine lakes framed by rich summer verdure. The production values are high. Elegantly lit domestic interiors, concrete-grey institutional settings, and the bodies that inhabit them, are made to seem immaculate. This is the backdrop for a seamless dream-like narrative, depicting scenes from the fictional lives of a number of non-binary and transgender protagonists.

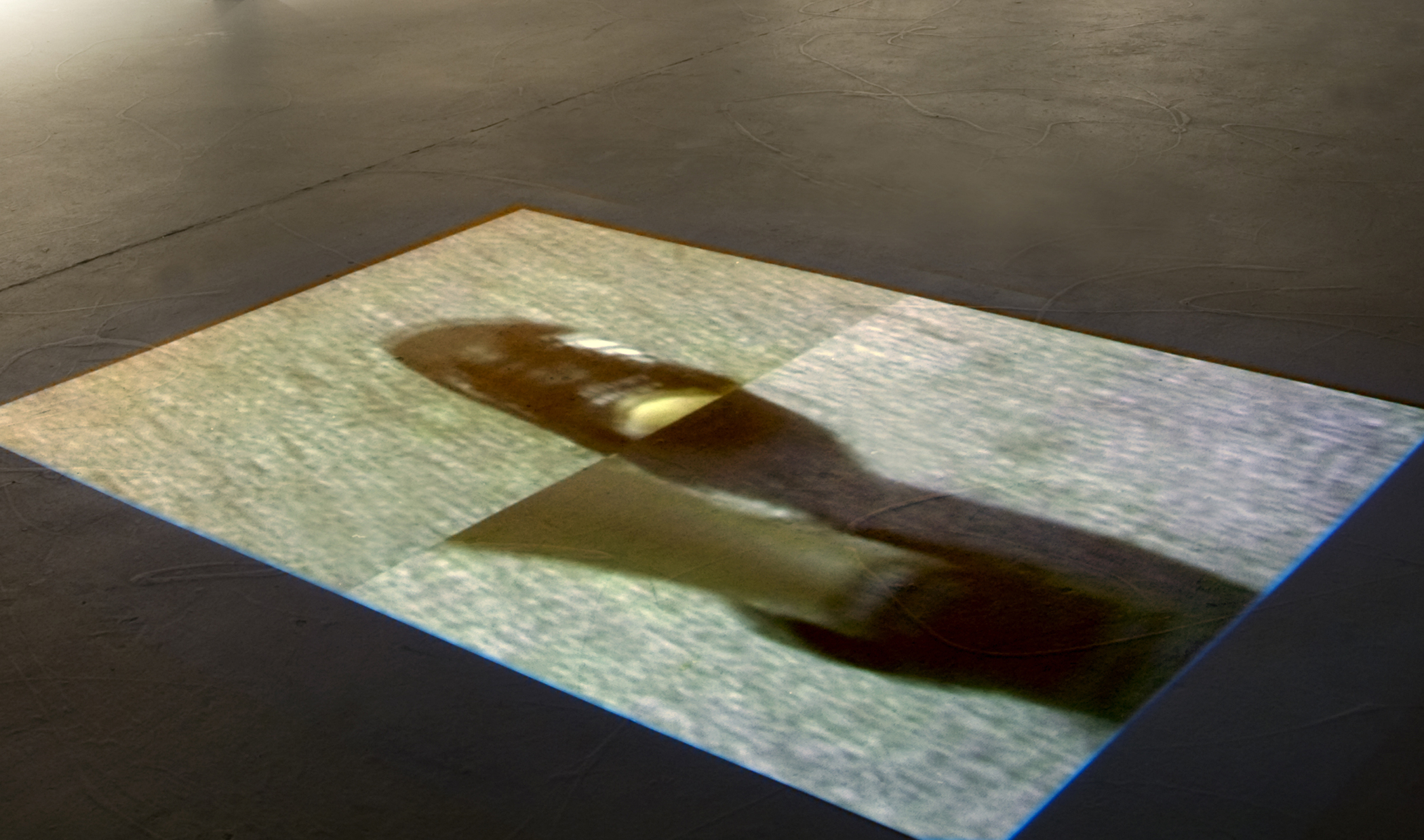

Doireann O’Malley

Prototypes I: Quantum Leaps in Trans Semiotics through Psycho-Analytical Snail Serum, 2017

Three-screen film installation, 33 minutes

Installation view

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, 22 June–14 October 2018

Courtesy of the artist

Photo: Ros Kavanagh

Prototypes makes explicit its commentary on psychoanalysis – and the ways in which the method has determined gendered subjectivity – with several scenes involving characters receiving psychoanalytic treatment. In one scene from Prototypes II we encounter the figure of Neo lying on a black leather daybed. Beside her, sits an analyst sits in a chair and takes notes. A dialogue ensues:

Neo: I find this label ‘wrong’ a bit tricky. Well, for myself I cannot … for me this is not the case. For other people I don’t know. It might of course be different.

Analyst: You are talking about the phrase ‘Being born the wrong gender’?

Neo: Yes, exactly. For me this doesn’t exist, in my case. I do not look at the world as if I am wrong; rather, it is the rest that thinks differently.

The othering of the self was understood by Foucault as a psychoanalytical process that shored up of the ego of those who conformed to a set of standards that had been universalised and assimilated. Neo refuses to see herself as a subject of this discourse. She expresses difficulty in seeing herself as ‘wrong’ or as other. Gender dysphoria becomes society’s problem, not hers.

Doireann O’Malley

Still from Prototypes II: The Institute for the Enrichment of Computer Aided Post Gendered Prototypes, 2018

Two-screen installation, 67 minutes

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, 22 June–14 October 2018

Courtesy of the artist

As this dialogue unfolds, a camera scans Neo’s body with a probing gaze as though the discursive examination of the subject prefigures a visual analysis and recording. There is something scopophilic about this process (‘scopophilia’, from the Greek: ‘look to, examine’), suggesting that the viewer derives some kind of sexual pleasure from looking – that bodies must produce and conform to a pleasurable ideal that has been registered in the unconscious. Anything other than this ideal is a cause for anxiety, abjection even. [5] A third gaze – one that doesn’t gain pleasure from looking – is also implied. The disembodied monotone voice-over suggests automation and, by extension, the machinic gaze. Its intonation is reminiscent of HAL 9000 from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey. In an increasingly administered world, images are often created and read by other machines; in some cases, humans have been left entirely out of the loop. For example, automated surveillance and face-recognition technology means that images are scanned by algorithms to be converted into sets of data. Is the machine who sees a cunt? The machine’s agency is a moot point but the panoptic vision of the machinic gaze certainly attests to an added anxiety of – either real or imagined – state-sanctioned snooping and corporate control.

Simultaneously, on the left-hand side of the split screen we see participants in a Live Action Role Play at the fictional Institute for the Enrichment of Computer Aided Post Gendered Prototypes gazing at small mirrors that might double as smartphones. The screen-as-mirror is analogous to our disembodied social-media proxies that reflect back to us the images we cultivate and the self-othering we enact though the prism of mediated consumption/communication. For all its benefits, the embrace of technology has been, at best, a double-edged sword. But the hysteria surrounding its possible authoritarian implications belies the complexity of the issues involved. Agency is still a powerful tool of contestation and, like all technologies, much depends on those who control the means of production. Prototypes hints at this radical technological potential with its art-historical echoes. During the analysis of Pol in Prototypes I, we are told about Goethe’s rebellion against his father:

I thought of the image of the father and how culturally the father is the representation of the law. It made me think about a story about Goethe. His father was pretentious; he hated his father. During this time in education everyone had to draw. It was the method of translation. His father forced him to make frames around his drawings and he hated this. You can see in his poems, his poems are framed in comparison to romantic poetry. Framing is a fatherly function.

Doireann O’Malley

Still from Prototypes I: Quantum Leaps in Trans Semiotics through Psycho-Analytical Snail Serum, 2017

Three-screen film installation, 33 minutes

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, 22 June–14 October 2018

Courtesy of the artist

The father’s capacity to reproduce and, by association, male (artistic) originality has been expressed and undermined in different ways by the historical avant-garde: Duchamp relegated the status of the father-as-omnipotent-creator to the state of a bachelor machine in his work of the same name. Andy Warhol’s wish ‘to be a machine’ can be understood similarly, though in his case it was also a strategy to escape the psychoanalytical/patriarchal gaze and its tendency to produce a subject.[6] This Oedipal hacking of technology for subversive gains through machinic projection is a tantalising prospect that promises a world beyond the tyranny of the father, beyond representation, open to post-humanist speculation:

The mirror, the piece of black glass through which no light can filter, lies a virtual utopia, a contemporary otherworld. A twenty-first-century world of alchemic spirits, symbols, and magic, a dream world in cyberspace which already points to the existence of parallel worlds, the possibility of the multiverse is inside there, within it, within you. Most of what matter is, is virtual. The virtual does not exist in space and time. They are ghostly non-existences that teeter on the edge of the infinite fine blade between being and non-being.

Doireann O’Malley

Still from Prototypes II: The Institute for the Enrichment of Computer Aided Post Gendered Prototypes, 2018

Two-screen installation, 67 minutes

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, 22 June–14 October 2018

Courtesy of the artist

The final scene of Prototypes II takes place in the evening, with the participants from earlier in the day gathering around to socialise at the bar of the institute. Music begins to play and everyone breaks into spontaneous dancing. We see a character called Nika retreat into a courtyard where a large monolith has appeared. He stands in front of the object. In the foreground, the mirrored windows elliptically reflect the jubilatory dancing of the figures inside. The monolith reflects nothing. Perhaps its smooth surface augurs the promise of an erasure of subjectivity. Perhaps it is, as the monolith from Kubrick’s masterpiece may have promised, a gateway to the next evolutionary leap.

Notes

[1] Jean-François Lyotard, Les TRANSformateurs DUchamp (Paris: Galilée, 1977), 133–38. In the French: ‘Con celui qui voit.’

[2] Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 76.

[3] For a Freudian and Lacanian reading of twentieth-century art history, see Hal Foster, The Return of the Real (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996).

[4] Ibid., 179.

[5] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. L. S. Roudiez. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), ‘The abject has only one quality of the object – that of being opposed to I. If the object, however, through its opposition, settles me within the fragile texture of a desire for meaning, which, as a matter of fact, makes me ceaselessly and infinitely homologous to it, what is abject, on the contrary, the jettisoned object, is radically excluded and draws me toward the place where meaning collapses. A certain “ego” that merged with its master, a superego, has flatly driven it away. It lies outside, beyond the set, and does not seem to agree to the latter’s rules of the game.’

[6] G. R. Swenson, ‘What Is Pop Art? Answers from 8 Painters, Part 1’, Art News 62, November 1963. Andy Warhol: ‘The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machine-like is what I want to do.’

Thomas Butler is an Irish curator and writer. He lives and works in Berlin. He established the nomadic curatorial platform ROOM E-10 27.