Cork City, 15.07.2017

3.30 p.m.

The mobile phone interrupts Saturday afternoon, a voice giving instructions, a script delivered in a bureaucratic tone like a corporate recording.

Immediately entering the pretence, I acknowledge the preparations I must make for my admission to Sanctuary at the West Cork Arts Centre. The call ends. I have two weeks to get ready.

I’m returned to my Saturday.

When Storm Ophelia hit the south coast of Ireland on 16 October 2017, the government announced the first red-alert weather status since the formation of the state. The storm moved northwards, leaving a trail of fallen trees, broken communication routes, electrical blackouts, deaths. Coincidentally, West Cork, the loci of the storm’s landing, was the site of Art Manoeuvres, a project by artists Sheelagh Broderick and Michael Holly, which had then been running for six months and focused on precisely the issues – emergency and survival – highlighted by the storm. Art Manoeuvres had been established to irritate the status quo, engaging new audiences in art and politics and generating new viewpoints at institutional, political, and personal levels.

In total, twenty-eight events took place over the six months of the project. In Clonakilty, Baltimore, and Skibbereen, workshops, screenings, and discussions were organised, accompanied by open calls for public interaction. These events provided a critical, aesthetic, and discursive platform, building a community of participants in dialogue, reflection, and knowledge sharing. Drawing on the manifesto for expanded practice produced in 2005 by ccred (Collective CREative Dissent), [1] Art Manoeuvres envisaged art as a continuous work in progress, developing a model of engagement that worked under the assumption that contributors were transient, growing or decreasing in size as the project developed. This framework invited participation to a number of locations over the course of the project and illustrated the potential to accumulate a significant body of collective knowledge.

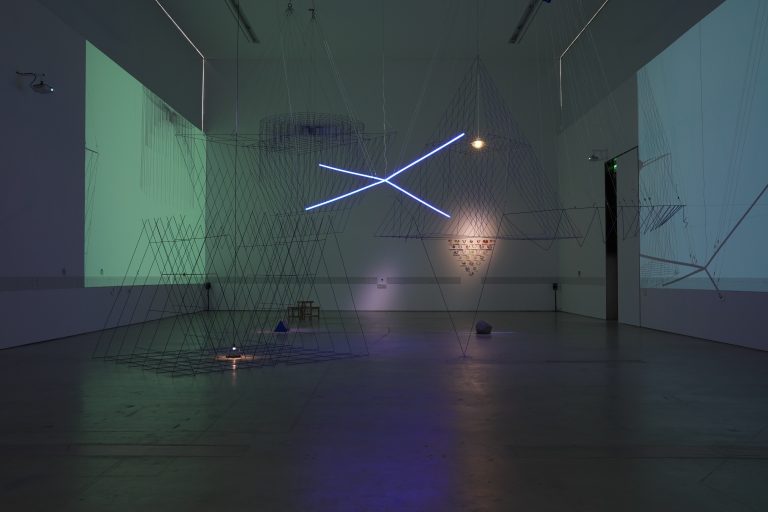

Sheelagh Broderick and Michael Holly, This Is Not a Dream

Documentation image

Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre, 29 July 2017, as part of Art Manoeuvres

Photo: Alison Glennie

This Is Not a Dream was the final event of the series. The call out posed a number of questions:

What if … you find yourself in the midst of an emergency and you are one of the lucky few to whom sanctuary is available. Obviously, you have many questions: Are you safe now? What exactly is the nature of this emergency? What does the future hold? How will you survive?

We were invited to the West Cork Arts Centre, Skibbereen, for an overnight happening ‘featuring film screenings, participatory games, workshops, light projections and dreaming’. In fact, this was the second overnight event that Art Manoeuvers organised, the first having taken place in Clonakilty earlier in the year. However, the aesthetic reach and ambition of this second event as a performative work of art pushed active participation into a more challenging immersive moment of co-determination. The event promised to ‘provide a platform to engage with pressing social and political issues on the theme of survival in a staged, immersive site’. Participants booked in advance, and later receiving a phone call in which the organisers asked them to invent an identity, including characteristics such as name, age, occupation, and reason for seeking sanctuary.

Skibbereen: 29.07.2017

6 p.m.

I arrive. I’m standing at the glass front door of the West Cork Arts Centre, a familiar building to me in a familiar town. Inside, directors wait, wearing expressionless white face masks and grey logo-stamped industrial overalls.

I enter. An echoing voice-over fills the art centre rooms: ‘This is a sanctuary … you must comply …’ A repetitive order accompanied by a discordant drone in the background. Directors reply efficiently to my questions in short, unelaborated sentences.

The other fourteen sanctuary seekers and I are processed.

Our data is collected, a psychological questionnaire filled, saliva samples collected, our hands scanned, our faces photographed, and our mobile phones taken from us.

I sit in the waiting area wearing an identification band, a white decontamination suit, and a surgical face mask. The instructional voice reverberates around the space. Screens display a director repeating the mantra of rules. He is more verbal than his real-world counterparts who are processing our group with a cool, distant, disaffected manner.

I wait in queue, watching with intrigue.

Is my privacy infringed?

I am vulnerable, I am being watched, I am watching, interpreting the cues. We all are.

This ‘sanctuary’ is unsettling

Another sanctuary seeker is belligerent: she will not wear the suit or mask.

I watch her noncompliance feeling uncomfortable – she knows something I don’t know, she’s not playing along. She is playing.

I watch as she backs down, choosing to stay – wearing the suit rather than being made to leave if she refuses … but I know she is not afraid to refuse.

Why does she want to make trouble?

I notice myself retreating into passivity; I will act when I have figured this out.

Prior to this, I knew the West Cork Arts Centre as a cultural space, somewhere to attend exhibitions or meet friends and colleagues. Spending time as a ‘sanctuary seeker’ not only shifted my perception of the centre, but also my role in that place. Simon O’Sullivan has written that fiction or fictiveness has emerged as an important category in recent art. [2] Artworks employ para-theatrical setups where the distinction between fiction and fact becomes blurred. [3] Coined by Jerzy Grotowski, ‘para-theatre’ describes a highly dynamic and visceral approach to performance that is aimed at erasing traditional divisions between spectators and performers. Artworks that use such setups involve the construction of a platform for experimentation. Public participation is essential.

In this instance, the cultural institution was transformed and reimagined as a clinical space for ‘processing’ people. The staging suggested a makeshift emergency situation. Objects were carefully chosen to fit the scene. There was a feeling of efficiency and accountability, conjured up by detailed props: logos, uniforms, masks, sterile white cloth, cameras, scanners, medical equipment, ID wristbands. A loud oscillating chord filled the space, uncomfortable to the ear. Under it, recorded voices imposed the rules of sanctuary coldly and repeatedly. We were surrounded by digital screens, and the directors silently observed and moved about us. Our personal items and identities were taken away. We had to comply. The art institution had become a quasi-military, social, health, or administrative setting. It did not feel like a sanctuary.

7 p.m.

Tour of Sanctuary, the eating zone, the sleeping zone, the meeting zone across three floors.

The claxon is ear piercing in this bare-walled space.

We go towards this sound as we gather in the meeting zone.

We share our names, our occupations, and the reasons why we are seeking sanctuary.

I have invested in this character after being asked to invent him two weeks ago.

My story contradicts others. None of us have the same reason for coming, we have not shared an experience that brings us here.

In the absence of a common external threat, the directors become the nucleus of our unification.

As the activities continue, a ‘pirate’ whispers in our ears, recruiting people for a mutiny.

She is committed to her story, but it doesn’t match mine. I’m suspicious of her motives, her move towards violence so quickly in the game – I’m a tree surgeon. Why would I want to take over?

The ‘back story’ to the staging – articulated in the call out – was the starting point to a shared narrative, but in fact it became just the premise for a co-determined improvisation that unfolded over the course of the night. The reconstruction was determined by the actions of the participants. The psychological and physical experience of being in proximity to the ‘regime’; the other ‘characters’ who had turned up as fellow sanctuary seekers; the sensorial immersion in the staged sanctuary: all fed into an improvisation. The actions and reactions were at once real and fictional.

9 p.m.

The eating zone.

As we eat, the directors leave us alone and a number of people in the group start to encourage a revolt. With unspoken consensus, they are the enemy. The game has momentum.

At the outset, Art Manoeuvres presented a particular narrative of power dynamics when emergency shelter is required. However, the relations of such staged fictions are never fixed. Even over the course of one evening, our experience was continuously being worked and reworked. The meaning that generated from this process could be considered a collective utterance. This is something different, demoting the individual and proposing a model of co-determination. On a personal level, the event exposed our values, assumptions, intentions, strengths, and vulnerabilities. At a collective level, the work opened up other worlds, other perspectives.

Sheelagh Broderick and Michael Holly, This Is Not a Dream

Documentation image

Uillinn: West Cork Arts Centre, 29 July 2017, as part of Art Manoeuvres

Photo: Alison Glennie

10 p.m.

Shock.

Four participants are separated from the group and are told, ‘You are the directors, you are in charge.’

Distress, refusal, followed by pressure, followed by compliance. Multiple splitting narratives emerge and clash. It is in turn hilarious, absurd, confusing, and disorientating. Rogue participants urge the new directors to ‘get the data’. A gun is reportedly stolen and hidden.

Four new participants arrive, and the newly formed directors process them wearing blank masks and uniformed in grey logo stamped overalls. The new directors are tactically friendly, but this seems even more sinister.

No participant in This Is Not a Dream had more information than those around them, and no one had access to scripts or proposed outlines, yet multiple propositions of the facts were at play. The directors are the enemy, our data is being collected to be used against us, we are powerless, and there is a gun. If we become a director, we will be isolated by the group – our capacity to change the situation is limited, and we can do whatever we choose. In the performance of our fictions within the real, we hovered between reality and fiction, embodying these alternative states.

11.30 p.m.

It is dark outside.

Through the large glass windows and doors of the arts centre, we have been watched moving from floor to floor in our masks, white decontamination suits and grey uniforms.

With courage fueled by alcohol, young revelers demand access to the centre. They pound and wallop the doors and windows shouting to be let into the arts centre.

This scene, viewed and heard from within by us sanctuary seekers, not only adds credence to our play, but the intensity of a potential breach blurs the line between reality and fiction.

They are a real threat.

They are just kids, having fun.

They might get in.

I am falling deeper into the fiction. We are all in character, but I am slipping between my character and myself: I am in flight or fight; I am immersed.

This Is Not a Dream continued into the night. The participants slept in the sleeping zone at 4.30 a.m. and got up the next morning for a shared breakfast, over which we recalled the event and our struggle to make sense of the shared world we had created and occupied. We discussed the assumptions we had made about the role and agenda of the directors, created in the absence of information, in the interest of group coherence. We talked about the psychological and physiological difficulty of maintaining character, while simultaneously reacting intuitively to our containment and the spontaneous improvisations that emerged through the ‘play’. According to artist Carrie Lambert-Beatty, these explorations are ‘a different way of being in the world […] the invented life […] a sidestepping of conscious intention so as to allow something else to come through’. [4] We talked about our inability to sustain the knowledge that this was an illusion, while striving to survive in the group, in the invented context, and in ‘the regime’. Most troubling was the close experience of being contained and controlled and our personal reactions to it within the group dynamic. The experience illustrated the extraordinary potential of worldmaking to generate associations, responses, interactions, attitudes, revelations that could not have been predicted. The fiction operated as a means of probing and revealing the fragility or strength of the attitudes and values we claim to hold, both personally and collectively.

Writing on ‘fictioning’, O’Sullivan has said that this kind of work can be seen as having indirect political and ethical potency, alongside an aesthetic charge. It contributes to the mapping out of the status quo and highlights different ways of being, different perspectives that might contribute to the creation of alternative modes of existence: ‘It is this performance – a staging or presentation of difference – that works to open up another world from within this […] whilst also demonstrating, through a reflexion, the fictional nature of any given reality, including the one we habitually exist within. […] It is this […] that gives the[se] kinds of practices […] an urgency beyond their aesthetic value.’ [5]

One could argue that in the present moment of political unrest in particular, the performative dimension of fictioning might be especially valuable as a means to reflect on the abilities of media to manipulate, polarise, and entrench opinion, and encourages us to ask ourselves how we can navigate through this new era of post-truth politics.

Art Manoeuvres situated itself between what is and what could be, an expanded practice that was both a critique of the present and a call to the future. It was a part of the place where it happened, West Cork, and yet apart from it in time, imagining potential futures. One could think of the project as a kind of tuning in, as a means of being receptive, of listening to other voices and other experiences.

Notes

[1] Simon O’Sullivan, ‘Four Moments/Movements for an Expanded Practice (following Deleuze, following Spinoza)’, Issues in Contemporary Aesthetics (May 2005): 67–69.

[2] Simon O’Sullivan, ‘Mythopoesis or Fiction as Mode of Existence: Three Case Studies from Contemporary Art’, Visual Culture in Britain 18, no. 2 (2017), https://www.simonosullivan.net/articles/Mythopoesis_or_Fiction_as_Mode_of_Existence.pdf.

[3] Simon O’Sullivan, ‘The Aesthetics of Affect: Thinking Art beyond Representation’, Angelaki 6, no. 3 (2001): 125–35.

[4] Carrie Lambert-Beatty, quoted in Simon O’Sullivan, ‘Mythopoesis or Fiction as Mode of Existence’, 15.

[5] Ibid., 14.

Marilyn Lennon is an artist and lecturer. She lectures at the Limerick School of Art and Design, LIT, where she is joint programme leader of the MA in Social Practice and the Creative Environment (MA SPACE).