At the centre of Fred Wilson’s exhibition Afro Kismet at Pace Gallery in London, a Yoruba Gelede mask is placed on a pedestal between two tiled walls covered in azure Arabic script, and beneath two hanging chandeliers. One wall proclaims ‘Black is Beautiful’, the other ‘Mother Africa’. The chandeliers combine Murano glass and Ottoman metal work, products of the long commercial trading history between Venice and Istanbul. Underneath the Gelede mask, worn during Yoruba ceremonies honouring the spiritual power of mothers, is a fragment from a European painting of a black women in Ottoman robes. This intersection of images and objects generates the stories Afro Kismet wants to tell, stories it reveals as all too rarely told.

Surrounding this central axis are more examples of nineteenth-century European paintings of black Ottomans that treat their subjects with a clichéd exoticism: The Carpet Bazaar, Cairo (1843) by William James Müller; The Musician (ca. 1895) by Rudolf Ernst. Three displays, covered in opaque plastic, present European prints of life in the Ottoman Empire, acknowledging their Orientalism without making it the centre of focus. Instead, small holes cut through the plastic reveal the presence of black figures that are always peripheral, yet all the more accepted for not being in any way remarkable.

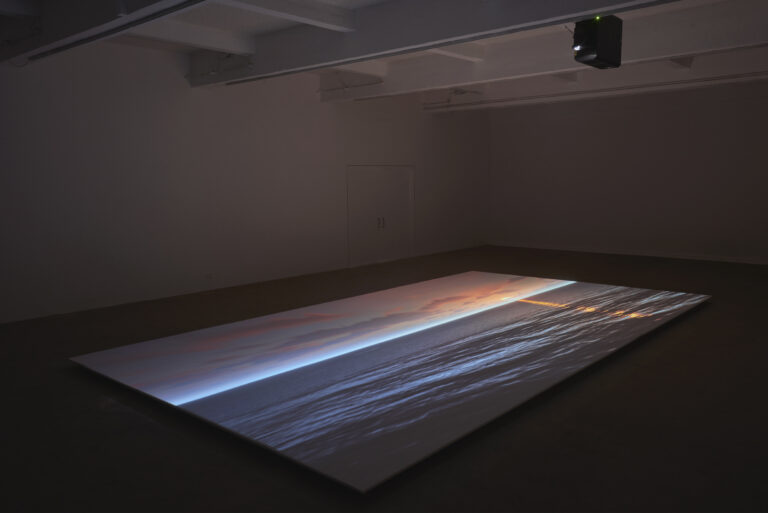

Fred Wilson

Installation view, Pace Gallery

© Fred Wilson

Courtesy of Pace Gallery

One vitrine, Nothing Ever Goes Away (2017), presents photographic portraits of black Turks posing with all the comfort of a confident bourgeoisie: a tense headscarved mother sits beside her smiling bareheaded daughter; two men pose outside in fields, seemingly oblivious in three-piece suits to the evident heat; a young girl smiles in the studio of ‘Turk Fotograph’; four black soldiers survey land for the Heilograph Department of the German Colonial Forces. These photographs represent the lives of black Ottoman and Turkish people not as the languishing remnants of centuries of slave trading or as the noble Moors of European fantasies, but as active participants in Ottoman and Turkish modernity in all its complexities and contradictions: its embrace of new media technology, its fatal alliance with Germany, and its transformed relationship with its traditions.

Wilson’s interest in using art installations to recover the obscured histories of the African diaspora can be traced back to his seminal 1992 exhibition Mining the Museum, where he re-curated the collections of the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore to expose the role of museums and art institutions in erasing and simplifying African-American history: iron slave shackles inserted into cabinets of antebellum silver pitchers. Afro Kismet was first created for the Istanbul Biennial in 2017, where Wilson took the opportunity to research the history of the city’s black African residents, a sequel to his similar excavation of the African history of Venice for the Biennale in 2003. One sign of the link between these projects is the presence in Afro Kismet of Othello, Shakespeare’s Venetian Moor, as imagined by stock nineteenth-century graphic illustrations. But the historical connections between Turkey and Sub-Saharan Africa are also shown by examples of the West African sculptures Wilson encountered in Istanbul market places, though never in Turkish museums: a Punu mask (ca. 1890) from Gabon, a Lobi figure (ca. 1890) from Burkina Faso.

Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson

Mother Africa

Iznik tiles, 281.5 cm x 583.6 cm x 1 cm

Installation view

© Fred Wilson

Photo: Damian Griffiths

Courtesy of Pace Gallery

This latest episode in Wilson’s career aims to do more than repeat the often-easy exposures of institutional critique. The European prints and paintings on display acknowledge the erotic hatred Western women (and men) projected on to Othello, but they are scattered around the margins of the room. At the centre, spatially and conceptually, is what the young black girl in the Turk Fotograph photography studio might have thought about Gelede masks – which might have been not very much at all.

The exhibition as a whole bears the scars of a transplant. The entrance to Pace Gallery, which occupies a corner of London’s Royal Academy, is flanked by statues of Adam Smith and John Locke. When drafting the constitution of British colonial Carolina, Locke wrote: ‘Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever.’[1] Smith might have been opposed to slavery, but only because it was inefficient, a distinction he believed was beyond the comprehension of the ‘savage nations’ of Africa. These histories are present in Wilson’s exhibition: the sculpture Trade Winds (2017), a globe covered in thick brushes of black paint, depicts both the role of trading in spreading the Africa diaspora around the world and the ignorance of the white colonisers who created the history of that diaspora. But that ignorance feels accepted, rather than challenged, in an institution that is a living memorial to the science that enabled the conquest of that globe.

Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson

Installation view, Pace Gallery

© Fred Wilson

Courtesy of Pace Gallery

When researching the original Afro Kismet exhibition, Wilson made what he called ‘the delicious discovery’ that James Baldwin lived in Istanbul while writing parts of his novel Another Country (1962) without ever learning of the city’s African residents, and the coincidence led him to accompany some displays with extracts from Baldwin’s melodramatic saga of inter-racial and bisexual love in 1950s New York. Baldwin thought he was escaping the pressures of race by fleeing to Istanbul, yet perhaps the presence of black Turks enabled Baldwin to claim the ultimate freedom, which is the freedom to be anonymous.

Afro Kismet’s nod to more recent history is a series of paintings located on the upper walls of the exhibition room depicting the flags of African nations, including those colonised by the Ottoman Turks: Sudan and South Sudan. The flags are monochrome, as if lamenting that the project of African independence is incomplete, the fervor of national revolution now faded. With these flags marking the limit of the exhibition’s engagement with Africa’s present, Wilson may share more with Baldwin than some lines from Another Country. There are an estimated 1.5 million people of Sub-Saharan African descent living in Turkey today; many lack visas, workplace rights, and legal protections, in spite of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s positioning himself as a friend to the unelected rulers of African states. Black pain is present in the show, but it is pain in the form of glittering black drops of glass that drip down the walls, safe under the eyes of Smith and Locke.

[1] John Locke, ‘The Fundamental Constitution of Carolina’, in Locke: Political Writings, ed. John Wootton (Cambridge: Hackett, 2003), 230.

The show ran from 23 March to 27 April 2018.

Kevin Brazil teaches English at the University of Southampton. He lives in London.