The opening of the 1938 Disney short Ferdinand the Bull, a Technicolor pastoral picture, presents a quaint miniature village comprising a compact, but towering, castle embedded in a small hill, snugly surrounded by a smattering of houses, cascading upwards and around, adorned with red clay roof tiles and sun-kissed white façades that evoke the impression of discoloured pearl (or faded manila paper). Panning downwards, we are greeted by a typical bucolic scene. A tree, possibly a stone pine, wider than it is tall, sits on an elevated meadow where three, and then four, brown and lighter brown calves skip joyously and playfully butt heads. A single bull-calf, mostly black but with a white nose, blaze, and underbelly, appears detached from the communal frolicking, approaching the foreground aloofly before the shot cuts to a close-up of him stopping to smell a blue flower. As the animation continues, our narrator informs us that the titular character is very much unlike the other calves, preferring to sit all day sniffing flowers under a cork tree (the depiction of which is sprouting literal corks for effect), rather than doing whatever it is an animal of his kind usually does or is expected to do.

In a short text written in the late 1970s, the always idiosyncratic philosopher of communication Vilém Flusser described cows as ‘structurally complex systems’ whose simple and elegant design made them ‘efficient machines for the transformation of grass into milk’. [1] Of course, this is only applicable insofar as the animal is understood and categorised within a chain of human agricultural (and industrial) production. Several years pass, according to the narrator. Five men come to inspect the – now fully grown – herd, and the other bulls perform theatrical feats of strength, trying to impress and earn selection from the humans. Ferdinand remains indifferent to their presence but inadvertently ends up demonstrating his suitability for bullfighting when, having been stung by a bee, he temporarily goes berserk, trampling through a brick wall before colliding with the other calves, sending them all comically catapulting into the sky. Unaware of the animal’s peaceful temperament, the men bring Ferdinand to Madrid, where he proves uncooperative with the matador in the bullring. The humans are frustrated at being denied their violent spectacle. Ferdinand is returned home and allowed to sit underneath the cork tree in his meadow.

Sarah Browne, Buttercup, film still, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sirius Arts Centre.

Cattle are one of the earliest subjects of human representation, appearing in the famous cave paintings at Lascaux and elsewhere. Later, they were a regular feature of the landscape genre, serving as extras or at times even the main characters in paintings by artists such as Paulus Potter and Thomas Gainsborough. Herein their most frequent function was to serve as a backdrop for some form of idyllic fantasy. Ferdinand the Bull diverges from these kinds of representations in its attempt – blunt and exaggerated as it may be – to project human qualities and characteristics onto the animal. The moral here is that it’s okay for everyone (human or otherwise) to be different. In addition, and perhaps more interestingly, the film seems to suggest that animals might possess an interior world not necessarily beholden to the narrow demands of the human realm.

In this, Ferdinand reminds me of Sarah Browne’s pet cow Buttercup, who plays a central role in her recent film, and exhibition, of the same name. Buttercup departs from a square format photograph taken on the day of the artist’s Holy Communion, displaying her in a white dress standing in front of her father and the heifer. The film’s emphasis on a single photograph, as a vehicle to unlock memory and explore the concept of interpretation, is reminiscent of the photograph examined at length in Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, the socalled Winter Garden Photograph, an image of the theorist’s mother and uncle standing together as children ‘at the end of a little wooden bridge in a glassed-in conservatory’, which Barthes used to conduct a ‘cynical phenomenology’ into the noeme of photography. [2] Browne’s narrative approach is similarly mired in uncertainty, saturated by her sense of the unquantifiable excess that resides within images. The voice-over that introduces the film says as much, noting that the difference between a secret and a mystery in art is that the revelation of the former exhausts the work (i.e., it is ‘solved’), while with the latter there always remains ‘a surplus to return to’.

Sarah Browne, Buttercup, installation view, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

The film itself took up two screens at Sirius Arts Centre. The larger screen featured moving images (almost still in their pensive slowness) of the family farm shot on 16mm film. There is something about the analogue film format, like hand-drawn cartoon style used during the golden age of Disney animation, that exudes a sense of warm melancholy. A lot of this attraction can be attributed to nostalgia – in our digitally saturated reality overflowing with constantly shifting, crystal-clear, images, our eyes and brains yearn for the soft glow of analogue imperfection – but they are potent all the same. Analogue can also have the effect of making time feel out of joint. While I know this footage has been shot recently, the flickering haze and noise of the film, in combination with the depopulated environments, generate an aesthetic force that disrupts the work’s temporal status, making it oscillate smoothly between the present and some vague and indeterminate past. The work plays with the effects of memory, through which the past is always updating itself, appearing brighter and more hopeful than it often may have been.

In the film, a buttercup field lies in front of a pond. A yellow jumper on a rusted gate blows in the wind. We see a close-up of flies on manure, a group of cows snacking on moss from a tree, the interior of a shed with a diagonal beam of light cast against the wall, coniferous trees peeking through an opening. These images appear yellow-tinged and hazy, sunlit with a consistency and intensity that seems uncharacteristic of the Irish weather. Against this backdrop, a multi-threaded story is woven through narrated voice-over, focusing on memory, a central thematic that allows Browne to touch upon ideas of childhood, human-animal relationships, bovine perception, gender, and disability. The singular photograph is returned to again and again, not so much as a device to push the narrative forward, but rather as a lens through which multiple lines of flight can open up, without seeking any kind of definitive resolution. We learn about Buttercup’s penchant for butter and sugar sandwiches, and about Talack the wild goat (and her descendants, all of whom inherited her name) who could not be tamed and lived outside the ‘numeracy, technology, governmentality, absolute purpose’ of the farm-system. The script oscillates between poetic rumination and austere description, both of which are deeply embedded in the form and concept of the work.

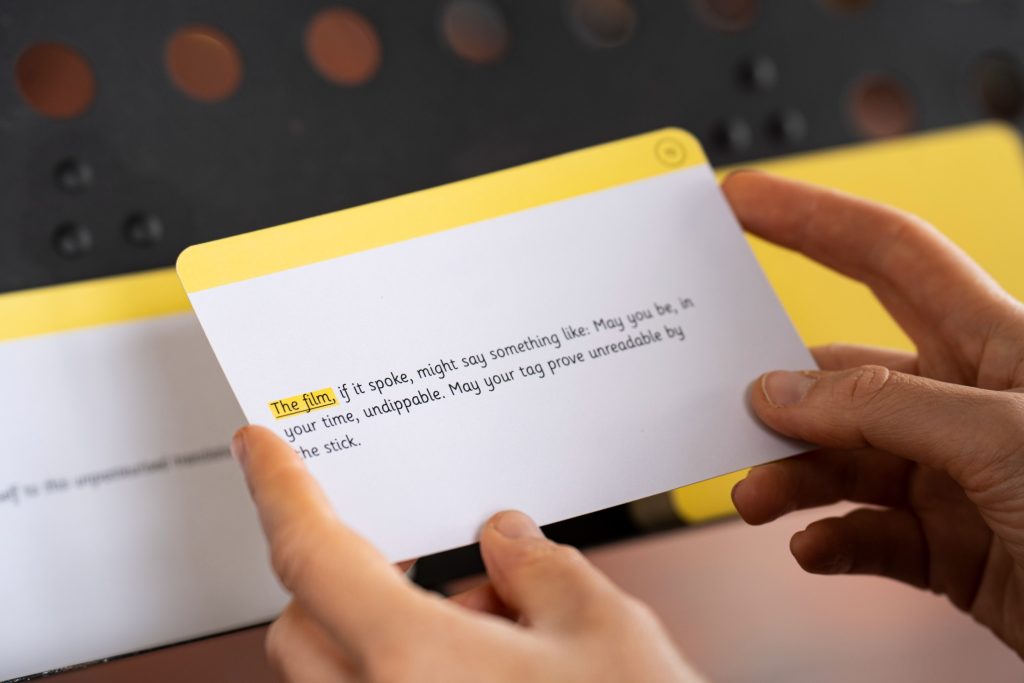

Sarah Hayden, ‘as if […] wearing ankle socks’, exhibition publication for Sarah Browne, Buttercup, Sirius Arts Centre, 2024. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

Within the installation, the main screen plays two consecutive versions of the film. A smaller screen functions as an accompanying display. During the first run, it plays closed captions, while in the second run it is left static – simply displaying the text ‘[audio description on]’ – with the main screen itself now supplemented by additional audio description. A key component of the work’s exhibition is exploring how art can be made more accessible to a larger audience. About a year and a half before the show, the White Pube (Gabrielle de la Puente and Zarina Muhammad) delivered a talk at Sirius as part of an artist residency. During the proceedings, De la Puente recounted a visit to Tate Liverpool where she was shocked to discover the lack of accessibility options for works in the museum. This prompted a conversation, after the talk, about the presence of closed captioning in cinema, and how it can often have the effect of anticipating aesthetic experiences for the audience. [3] Much art works better when it is implied rather than forcefully stated. It may be due to my background in music, but I can’t help raising an eyebrow when on-screen captions tell me what the score is supposed to sound like. However, Browne’s Buttercup offers a more nuanced take on closed captions and audio description. The artist worked closely with audio-describer Elaine Lillian Joseph to develop the film, resulting in something that the artist refers to as a ‘poetics of audio description’. [4]

In Browne’s film, the audio description doesn’t feel as if it’s offering a diluted version of events, but rather an alternative interpretation. This is an approach rooted in the practice of ekphrasis, a rhetorical device derived from an Ancient Greek tradition that seeks to produce a written description, quite often poetic, of a visual image. Ekphrasis is, and always has been, a fundamental component of art criticism, conceived as an attempt to elevate ‘mere description’ (which, in its purest form, would consist of nothing more than a literary tautology of visual form) into the realm of poetics; a form of writing that can stand independently alongside the work of art. This approach is also at work in writer Sarah Hayden’s text for Browne’s exhibition, titled ‘as if […] wearing ankle socks’. Effortlessly blending poetics with the essay form, Hayden’s response, delivered initially as a live performance and available for reading in the gallery as a series of loose leaf index cards, uses the film as base material in order to perform a speculative commentary that imaginatively explores the possibilities suggested by Browne’s work. Through the multitude of ways in which the work is delivered sensorially for the audience, new and varied facets of Buttercup emerge. (Listening to the audio-description version reminded me of the experience of a radio play, as moments and details that had escaped my initial viewing were brought to attention.) The rustic illusion of the agricultural setting operates, in this sense, as a proxy for art at large, with its capacity to ceaselessly extend, subvert, and reform our perception of the world anew.

Laurence Counihan is an Irish-Filipino writer and critic based in Co. Kerry. He is also a teaching assistant and PhD student in the History of Art Department at University College Cork.

Notes

[1] Vilém Flusser, ‘Cow’, Natural:Mind, trans. Rodrigo Maltez Novaes (1979; repr. Minneapolis, MN: Univocal Publishing, 2013), 43.

[2] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982), 67, 20.

[3] Sergei Eisenstein’s film theory stresses how cinematic montage generates new meanings that are not inherently present in the original, individual, images. Extending this theory outwards to encompass sound, it can be proposed that to achieve maximum aesthetic impact, the audio component of a film should strive for a similar degree of dialectical conflict. See Sergei Eisenstein, ‘A Dialectic Approach to Film Form’ (1929), Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, trans. Jay Leyda (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1969), 45–63.

[4] Sarah Browne, quoted in Colette Sheridan, ‘Cork-based Artist: Pursuing a Meaningful Life through My Art’, The Echo, 4 June 2024, https://www.echolive.ie/corklives/arid-41408390.html.