Jaki Irvine’s work often begins with something she has heard or seen elsewhere. The artist’s recent exhibition at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, Shh Ow (the second syllable can be pronounced like ‘oh’ or ‘ou’, whichever you prefer), features an installation, Ack Ro’ (2019), inspired by Neil Diamond’s 1970 hit song ‘Cracklin’ Rosie’. ‘I wasn’t such a great fan, I have to admit,’ Irvine says of the song, in a video interview accompanying the exhibition. ‘But at a particular point this CD was being played all the time in my mother’s house.’ [1] Gradually, Irvine realised that her mother’s repeat listening to Neil Diamond’s greatest hits was an early symptom of dementia. Attempting to evade the situation, the artist took a trip to the ‘other end’ of Ireland where, having just sat down at an Indian restaurant, she realised the same album was playing in the background once again. Ack Ro’ takes its title from the letters and punctuation of a song that, accompanying the dawning awareness of her mother’s illness, she couldn’t seem to shake.

Jaki Irvine: Ssh Ow, 2025, Installation View, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-On-Sea. Photo: Rob Harris.

Memory and the process of losing it – how it splinters and scrambles, retreats and returns – serve as the governing metaphor of Shh Ow. As in much of Irvine’s other work, she does not restrict herself in medium: the components here included audio-visual installations, text, live and recorded music, and computer-generated imagery. Ack Ro’, which was previously shown at galleries in Dublin and London, consists of an arrangement of thirteen flat-screen monitors and twenty-eight pink neon signs in a single gallery. The signs extend the gambit of the work’s title, forming partial anagrams – some real words, others nonsense – of ‘Cracklin’ Rosie’. (As Irvine noted, the song itself performs a kind of word play: the titular character, according to Diamond, is not a woman but a near homonym for a brand of cheap sparkling wine popular with a particular Indigenous tribe in Canada.) ‘Licks rail’, ‘ack’, ‘near so near’, ‘o’: these fragments of meaning are dotted seemingly at random around the room – at various heights on the walls and glass window, behind a monitor – all glowing in the pink looping font. The choice of neon, verging on kitsch, makes sense: what could be more nostalgic?

Jaki Irvine: Ssh Ow, 2025, Installation View, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-On-Sea. Photo: Rob Harris.

The monitors are similarly arranged: propped on the floor, suspended from the ceiling, or affixed to the wall like a regular TV. Three are synced up, showing an improvised performance developed in collaboration with a singer (Louise Phelan), a flautist (Joe O’Farrell), a pianist (Izumi Kimura), and a percussionist (Sara Grimes). Irvine instructed the musicians to alternate between ‘holding on’ and ‘letting go’ – or, putting it another way, remembering and forgetting – in their call-and-response interpretations of Diamond’s ‘Cracklin’ Rosie’. The recordings, both audio and video, were then layered to create a kind of abstract collage of performers and instruments, melody and noise. Perhaps the best adjective to describe it is ‘haunting’. Playing on the other nine monitors, meanwhile, are looped videos of varying lengths, framing everyday images and sounds from the urban landscapes in Dublin and Mexico City – the two cities where Irvine lives and works. There’s a close-up of a pink lily; the exterior of a building covered with mesh sheeting, gently blowing in the wind; a busy street scene with a blurred-out birdfeeder in the foreground, parked cars and stacks of coffins in the background. The ambient noises from these scenes add yet another layer to the musical soundscape. Time and space are collapsed: it’s everything everywhere all at once.

Jaki Irvine: Ssh Ow, 2025, Installation View, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-On-Sea. Photo: Rob Harris.

For this latest showing of the installation at the De La Warr Pavilion, Irvine added two new elements. The first was a mesh banner, twenty-seven metres long, covering the exterior glass windows that run along the south end of the gallery overlooking the sea. (The idea came from the sheeted buildings that appear in a couple of the videos in Ack Ro’.) Printed on the banner was a computer-generated image of shards of red glass against a cloudy sky – yet more shattering and fragmentation. From inside the gallery, the banner functioned as a kind of veil; the people and the buildings on the seafront were still visible but hazily – to use Irvine’s own lovely phrase, as if ‘already memories somehow’. But the more significant new work, perhaps also influenced by the gallery’s coastal location, was a full-scale live performance that took place during the show’s closing weekend on 24 May. SHWO EM THE WAY OT GO HMOE once again scrambles the letters of a song title: this time, the popular 1925 song that most famously appears in the legendary coastal thriller Jaws (1975). Irvine has not referred to any personal significance that ‘Show Me the Way to Go Home’ might hold, but she has mentioned that it tends to be performed – both in Jaws and other films, books, and so on – during moments of crisis. Like ‘Cracklin’ Rosie’, it is also a song that describes the state of inebriation, which may be the closest those of us without dementia can get to the disorientating experience of memory loss.

Jaki Irvine, SHWO EM THE WAY OT GO HMOE, performance as part of Ssh Ow, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, 24 May 2025. Image courtesy De La Warr Pavilion.

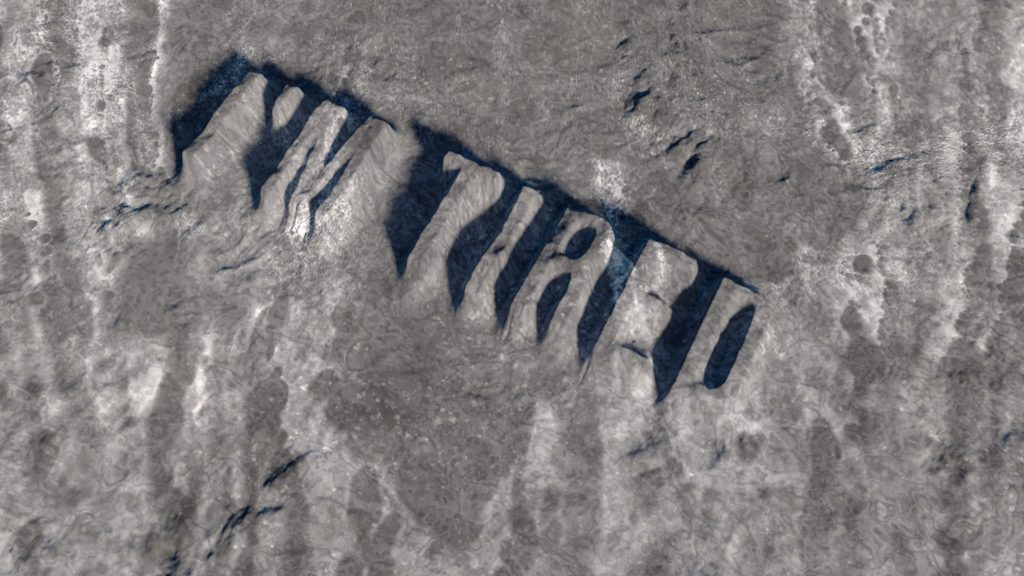

Over the course of two hours in the De La Warr Pavilion’s large auditorium (where, on other occasions, acts including Lee Scratch Perry and The Kooks have appeared), the improvised performance unfolded. Irvine, VJing on a desk in the corner, provided the ‘visual score’: a mix of recorded and found footage and computer-generated imagery, projected on a screen at the back of the auditorium, that the musicians – the four who performed in Ack Ro’ plus a cellist (Tara Frank) and saxophonist (Cath Roberts) – were charged with interpreting. Projected lights cast spiral patterns on the floor. If this sounds like a lot to take in, it was. Among the things that I noticed appearing on the screen were the phrase ‘I’m tired’ pulsing in sand, the letters scrambling and unscrambling; numbers floating on a watery surface; black-and-white rope coiling; ships at sea. The sounds were similarly varied: words and phrases, sung on repeat; high-pitched beeps, unpleasantly sharp; snatches of more melodious tunes. At one point, the pianist dropped a small ball into the instrument’s soundboard, where it rolled around, apparently noiselessly – at least from my seat in the audience. The cumulative effect was, as in Ack Ro’, that of details vaguely or partly discerned.

Jaki Irvine, SHWO EM THE WAY OT GO HMOE, 2025, film-still (visual score). Courtesy the artist.

Perhaps, as a final note, I should mention that before visiting Shh Ow I had never heard ‘Cracklin’ Rosie’, nor had I seen Jaws. I also didn’t know the story about Irvine’s mother being diagnosed with dementia. In a way, this lack of context was appropriate for the experience of the exhibition, heightening my sense of confusion as I tried to understand its garbled messages in text, image, and sound. The evening after the performance, however, my need for clarity won out. On the flat-screen TV in our Airbnb – rather conventionally centred on the wall in the living room – my boyfriend and I watched Jaws. ‘Show Me the Way to Go Home’, it turned out, is sung near the end of the movie, during the climactic sequence in which the three protagonists go out on a boat to hunt the shark that has been terrorising the island of Amity in New England. At nighttime, the men retire to the cabin where they get drunk and start singing. They are interrupted when the shark surfaces, ramming hard into the hull of the boat. While watching, I began to spot images and lines which had appeared in SHWO EM THE WAY OT GO HMOE – recent memories, still fresh in my mind. Even now, as I write this just a few days later, these memories have begun to fade.

Gabrielle Schwarz is a writer based in London.

Notes

[1] All quotes in this text are from a recorded interview with the artist on the occasion of the exhibition.