Adrian Duncan: When the other editors of PVA and I alighted on the theme for volume 12 – touch – a work of yours sprang, one morning, into my head. It was a painting I saw a few years back titled Mespil Road Petrol Station and Canal (2013). One of the many aspects of the work that interested me was the relationship between the petrol-station roof and the reflection of this roof on the foreground. I found myself wondering about the kind of projecting that was going on between the interfaces that are alluded to in the painting. This then led me to thoughts about what might happen in actuality when a painting is being composed – the movement of ‘unorganised’ material from plate or glass to the ‘more-organised’ material on the canvas or board.

I wonder could you tell me something about how this movement, this kind of construction, happens? How do you begin?

Mairead O’hEocha: While I have a thematic approach to a new body of work, most of the individual works start with a real-life encounter with a place or an object. Mespil Road Petrol Station and Canal was one painting in a series I made in 2013. I took to walking along the Grand Canal just before nightfall close to where I live and started thinking about Edgar Allen Poe stories, missing people, lost objects, secret crimes, night water, and city lights. I was entranced with how the water played its own parallel narrative within the mud and concrete frame that surrounded it. I was also taken with the light changes at dusk – how when night arrives gravity and certainty slip away, a point in time that marks a state of mind between material and metaphysical worlds.

Artificial light sources at night converge on a physical structure and seem to cancel out the actual planes and surfaces of a structure, creating something else entirely … a more suspect and illogical arrangement of planes, so that light draws/paints the scene on its own terms. In this painting the reflection on the water reads to me like a ‘trapdoor’, and is another route to consider illusion, artifice, and the dissolution of form.

AD: I like this idea that as one source of light fades, another emerges: this brings about a sort of inbetween state for your thoughts and observations to form.

While you were working on this piece, did you find yourself bound in any way (was there a fidelity) to the initial impression of the site itself or did the complexity of the paint as it was being applied lead you off into entirely different directions in terms of mood, let’s say, and tone?

MOH: The site itself is a jumping-off point so there is a whole lot of slippage between the motif and the real site. I don’t know what I am specifically looking for and this is for me the point of making a painting. So it is instinctual and intermittently entirely conscious. I am trying to learn something new, whatever that might be; a technical discovery about combining colour harmonies or something about composition. I hope for abstract ideas to emerge and play out. For me painting is a means of manufacturing virtual space and I like how it can bridge a sensory self with the physical world, managing an interior and exterior experience simultaneously. I choose real and specific places that I know and live in and create/edit elements to communicate something more symbolic and universal.

The push-and-pull process between the original image and the finished painting is one of discovery, experimentation and research, and then a final ‘trade off’, so that the last stages can sometimes feel like finding the missing clues for solving a homemade Rubik’s cube. The process involves several drafts and edits, much like the act of writing and editing.

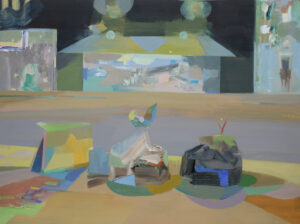

AD: There’s another work from this period of time that I remember spending ages looking at when I first saw it: Bags Waiting, Night (2014). It is another ‘street’ scene of a kind. Did this work also come about from those walks taken in the evening near to your home? And how did this strangely active (and beautiful) title come about? I find the relationship between the titles you give these works and the paintings they ‘point to’ a source of unending interest. Do the titles of works emerge to you as the painting does? Or is it very specific to the piece in question? Can you say something about the title of this work; it seems to me to hold much.

MOH: Bags Waiting, Night was made around the same period of time as the Mespil Road Petrol Station and Canal. I was aware that these common bin bags are made from polythene, which is mostly made from petroleum or natural gas. I am drawn to subjects that might contain evidence of some sort of physical/material change, colour temperature shifts from day to night … clouds moving to empty themselves of rain, and all the man-made forms of transubstantiation we live with every day. For me, there is a type of alchemy in the making of paintings. So the title in this case leans towards this interpretation. But I think Bags Waiting, Night is almost a non-title and allows a variety of interpretations. When I look now at it, they could be read as containers of some sources of information, and while they are set up like a still life, I think they could be people waiting in line for confession. While I accept the role of the viewer is to confer their own meaning and the artwork suffers when titles overdetermine the meaning of the work, I never liked the idea of naming works as Untitled.

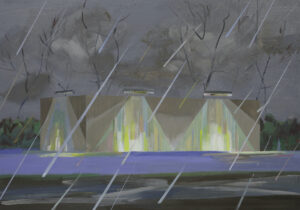

AD: Hoarding, Lights and Rain, also from 2014, is a work that raised a number of questions for me to do with colour and the placement of the ‘I’. I found the colours in this work bridged between being inappropriate to my expectation of hoarding lights on a wet night, but yet appropriate to the material, to the work. This sort of bridging effect I found to happen with ease in the other works from this time, but it seems in this piece that the falling rain proposed a sort of ineffable screen between me and the work. I felt there was at once a kind of distancing and embracing going on. And it made me wonder, in this fascinating push and pull: Is there a type of forgetting necessary as you explore a new work?

MOH: Yes, forgetting is a good way of thinking about this. To broaden the question beyond any specific work and answer it in terms of a new ‘body’ or ‘series’, the will to forget and reinvent myself is a natural impulse. Like turning the lights off in a room and on again, the idea that anything has really changed is an hallucination and a matter of perception. But releasing or discarding a view allows for the possibility of starting in a different place, and like many artists I want to avoid staying with a method or idea that might constrain. So when starting over and beginning anew there is a deliberate attempt to break from a previous approach and contradict what has gone before. This painting was one of four paintings that were exhibited in Gallery 2 at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin. I was aware it was a small windowless space and decided I wanted to create ‘openings’ to expand on this confined experience and make works that emitted and mirrored different light sources. Each work was one or other of the following: photographic/flashlight, florescent, daylight, and tungsten. I studied and worked as both a photojournalist and a still photographer so I know a bit about light and colour temperature and am fascinated with how it can help determine and/or complicate elements of a narrative within photography and film for psychological effect.

Mairead O’hEocha

Mespil Road Petrol Station and Canal, 2013

Oil on board, 43 × 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London

Mairead O’hEocha

Bags Waiting, Night, 2014

Oil on board, 44 × 59 cm

Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London

Mairead O’hEocha

Hoarding, Lights and Rain, 2014

Oil on board, 61 × 77 cm

Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London

So the painting is sometimes completely in debt to the structure of the photograph/place or site and then something happens and it evolves into something unrecognisable from the original photograph/site. My training is in analogue/chemical photography and my understanding of light is informed by its interaction with optics, lenses, and photographic materials – how light rays from the sun can physically strike silver halide salts and be chemically transformed and fixed into stable silver grains. I think my experience of growing up in a time that witnessed the transition from analogue to digital platforms informs my interest in what the painting can do that photography cannot. While the relationship between photography and painting, for me, is quite particular and interconnected, I also see them as being at cross purposes. The painting Hoarding, Light, Rain plays with the idea of additive/subtractive colour, how white light is actually the sum of all colours in the spectrum, while pigment works in the opposite direction becoming darker and muddier as more colours are added and mixed together.

When I use photographs as starting points, I try to ‘unmake’ them as photographs and turn them into new compositions in paint and pigment. I’m not sure if this is going to expand on what I mean, but I was really taken with what the band Icebreaker did with interpreting Kraftwerk’s music. Their work titled Kraftwerk Uncovered took the band’s original synthesised music, deconstructed it, and then rearranged it to be performed by a twelve-piece orchestra. I heard them play this live at the National Concert Hall in Dublin and it really struck me and stayed with me, this transformation of the flattened tones of the synthesised original, so carefully unpicked and recoded to make an entirely expanded and layered new work in its own right.

AD: There’s an Irish engineer, Peter Rice, whom I’ve been fascinated with over the last decade or so. His book An Engineer Imagines was published posthumously in 1993 – a year after his death. Rice was the structural engineer on some important postmodern structures (Centre Pompidou, le Nuage at the Arche de la Défense, the Pavillion of the Future, Seville, Lloyds Bank, London). In the book there is a chapter about an issue he sees emerging in the photography of buildings. He felt that the way buildings were being photographed was problematic because it was leading architects towards a style of architecture where how their buildings photographed was taking precedence over other important aspects of building. One of these other aspects was the building’s structure, which Rice felt was very hard to relate through a photograph. I’ve since thought about this in relation to art criticism and how artworks are themselves photographed (for industry magazines) and this then led me to the idea that describing artworks evocatively can reintroduce (however fleetingly) some of this structure that photography seems to flatten. I think your music example resonates greatly with this. (I had not thought in this context about this kind of restructuring from the position of musical composition.) It seems to me that colour is very important to you as you invent these working spaces. I wonder, is it so that colour and things like depth, width, height – dimensions – are independent things that become infused as you progress? Or is there an illustrative aspect to how colour is used in relation to these dimensions – these perspectives. May I ask you this question in relation to Tree for Missing People (2014)?

MOH: Peter Rice is an extraordinarily inspiring figure and I think his point about photography and buildings is valid. I guess photography is pretty well understood as an unreliable narrator in explaining the complexities of the material world. It continues to mislead and misinform in spite of/because of the ‘reality consensus’ it promotes, which is largely based on topical evidence. I like your idea and intention to elaborate on the art object through art criticism as a means to expand its reception and perhaps bring it out into a more volumetric experience.

The question of colour is a really good one, but also hard to untangle. I am interested with how colour in painting has evolved and how, for instance, modern eyes read colour in a different register than eighteenth-century eyes. Optical technologies continue to shape taste, and what we perceive as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ is clearly influenced now by our exposure to screen time.

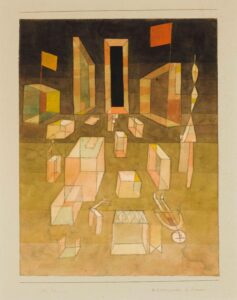

The painting Tree for Missing People evolved through multiple drafts and colour studies. It did start with a real tree along the Grand Canal, one I associate with tragic disappearance of Trevor Deely all those years ago.1 However there is no resemblance to the actual tree as I built/arranged it (branches, etc.) to form itself according to imagined colour relationships that describe how flashlight falls on a tree using condensed light and contrasty relationships. I think about the mediated or flattened world we experience and believe there is a loss in our spatial apprehension. I like to maybe see what I can get away with as an imagined form, so in this painting I was feeling my way through an arrangement of colours that might describe a semi-plausible tree in flashlight. The tree is enormously significant in historical and contemporary visual culture, but in this instance I was reading a lot of Paul Klee and his writings on colour and form. I was also thinking of an ancient and curious belief that the wind blowing from each direction has a special colour. The colours are associated with the compass, like a clock so that east is purple and southeast is red and so on. This is recorded in the famous Saltair na Rann,2 which is an Irish tenth-century text and narrates a sacred history of the world.

Going back to colour, I have a tendency to drift towards using blue and yellow, and while I have made deliberate attempts to confiscate these colours, there is often a leaning back into these parts of the colour wheel. Van Gogh talked about yellow and blue and how they belong to a more metaphysical domain perhaps because they describe atmospheric or climatic effects (sun/sky/water), whereas red and green are more earthbound, describing the material world, flesh and blood, foliage, and so on.

The act of making paintings, for me, is an infinite space that needs the full stop of a deadline. The finished painting is not the sum point of all of the time spent in the studio, but that full-stop moment is a bit like your home before someone comes to visit, when open diaries are closed and a rug is laid over a stain. The viewer/visitor can still sense or get an understanding of what may have happened before their arrival in the room.

Mairead O’hEocha

Tree for Missing People, 2014

Oil on board, 83 × 60 cm

Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London

Mairead O’hEocha,

Stray Centred Family, 2014

Oil on board, 60 × 80 cm

Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London

Paul Klee

Nichtcomponiertes im Raum (Uncomposed in Space), 1929

Collection of Franz Marc Museum, Kochel am See

AD: This idea of colour having ordinates or direction (on the wind) is really interesting. I came across a version of this recently too, while reading Hubert Butler’s Ten Thousand Saints (1972), where he suggests that the names of these colours can also be attributed to the movement of tribes from both within and outside of ancient Ireland – and by extension the origins and direction of their migrations. This drift between meaning and colour is an aspect of painting that fascinates me, but also, within this, I’ve always been struck by the impossibility of sources of light in paintings – almost as if the sources of light in a painting are constantly being moved around and the painter is at once apprehending, directed by and capturing something of this shifting illumination and the kind of strange internal space being carved out by it. Can you say something not just about light source but also about light position in one particular work of yours, also from 2014, titled Stray Centred Family.

MOH: I didn’t know about Hubert Butler’s connection between the associated movement of tribes and the labelling of colour with wind direction – that’s really interesting. I came upon a merry-go-round that was being put out of service for the night while visiting Genoa in Italy – it was early evening, that time of day which is in transition. The carousel appeared to be just about to grind to a halt, but its figures seemed to be all set to go a-haunting. I was thinking about Paul Klee’s Uncomposed in Space (1929) and his ideas for trying to create stray-centred perspectives.3 But I used them to play with light rather than forms or solids. I return to light a lot when thinking and talking about work.

The carousel and fairground as subject featured in a lot of early modern painting and it may have something, or a lot, to do with the zoetrope and other pre-film devices. The fairground and other forms of illuminations were really important for early modern painters, and I am always interested in painting during this period (1850–1940). These artists’ works are so compelling in their radical and experimental responses to the optical assaults of new media, like film and photography. The most apparent formal change was in painting’s shift of axis, relying instead more on colour than on linear means of modelling. I do think the extreme rupture for people in adjusting to the x-ray, the movie camera, and still film was significantly more explosive and profound than the adjustments that we are being asked to make in adapting to the continual changes we experience with digitised information. I am not underplaying the serious concerns of optical/technological advances, and of course the ‘deep-fake’ phenomenon and its potential misuse is pretty terrifying right now as are the advances in AI, identity theft, and all the other unquantifiable losses in our autonomy.

To go back to the question you asked, I am attracted to artificial light as it allows more creativity and experimentation in describing elements of the material world. I don’t make paintings that illustrate particular ideas and prefer things to be uncertain, more like a conversation. There has to be a balance of detachment and engagement; it’s about getting out of my own way and allowing the work to gain its own momentum because, in the end all my ideas and what I am interested in run parallel to the paintings themselves.

Notes

1 Deely was last seen more than twenty years ago on 8 December 2000 after he spent the evening in Dublin city centre with his bank colleagues following a Christmas party. Despite twenty years of Garda investigations and multiple false leads, his family still do not know what happened to the twenty-two-year-old.

2 Saltair na Rann, author unknown, is a collection of middle Irish verse that gives accounts of biblical history from the time of creation to the resurrection of Christ. The number of the cantos imitates the number of psalms in the Bible.

3 A number of objects, forms, and figures are oriented towards the black rectangle placed in the top centre part of the painting. Klee seems to comment on the notion of three-dimensional Euclidean space and the corresponding restrictions imposed by the rules of one-point linear perspective. The vanishing point located somewhere in the black rectangle magnetises and makes rearrangements impossible as everything seems about to vanish or get vacuumed inside this black hole.

Mairead O’hEocha is a Dublin-based artist. She is currently represented by mother’s tankstation Limited, Dublin / London.

Adrian Duncan is a writer and artist. His most recent novel, The Geometer Lobachevsky (2022), is published by The Lilliput Press and Tuskar Rock Press.

This Q+A was originally published in PVA 12.