In mid-2011, I started a three-month artist residency at the Leitrim Sculpture Centre in Manorhamilton, a village in the northwest of county Leitrim.

On one of the many roads in and out of the village, off to the right, lay an open area of wasteland. Rising up and out of that land stood a mound of rubble, brick, and stone. It was mesmerising – its very existence. There was also something sad about it: Had it been a family home in its former state?

Every time I passed this place, I stopped and stood in front of it, fascinated. It was like coming upon a large brutalist concrete sculpture in the middle of nowhere, left behind by accident or forgotten. This part of northwest Ireland is littered with tombs from the megalithic era, and this site seemed both part of that history and in conflict with it – familiar and unfamiliar.

I began to visit this mound of rubble every day, becoming obsessed with it. How did it come to be? What hand had a part in creating it?

I spent so much time there.

Walking around its perimeter, scaling its sides and pinnacle, or simply sitting on a stone, I needed to know more about it, to understand it. This physical anomaly seemed to have age to it, like the megalithic tombs scattered around the local landscape. The land surrounding it had begun to absorb the mound, with vegetation climbing up around its edges, and moss and other small bits of life clinging to pockets of soil between the blocks and stones.

This peculiar place spoke of time, space, place, scale, form, intervention, and encounter – all of which are concerns in my artistic practice. Was it a piece of sculpture I just hadn’t made yet? Could I adopt it as a work of my own? Could I adapt it as a work of my own? What would that entail?

It wouldn’t take much, I thought.

Like an archaeologist looking for clues, I began to survey the site and document everything through notes, drawings, and photographs. I noticed that a number of concrete blocks had a slight yellowness to them; a faint painted surface. In a previous state this was once a room, a bounded space, a bedroom or a kitchen. I decided to follow these crumbs, to fill in the gaps between then and now. To try and refine what was in front of me somehow. Intervention by means of tuning – of tuning a place. Bringing the past closer to the present. Reconstituting the room.

After collecting a small sample of this yellow-hued brick, I had an approximate colour mixed in a local paint store. Returning to the site, I began to paint all of the bricks with that yellow tone, with great care, almost reverence. It took some days, making sure I didn’t miss one and giving a second coat to most.

It was like I was bringing into focus something that had previously been out of focus. Even something of that size can disappear into the background, yet a small intervention can restore its presence. I believe some people even began to notice the place again.

I called it Mound, and it remained there for a number of years before it was removed and turned into a car park.

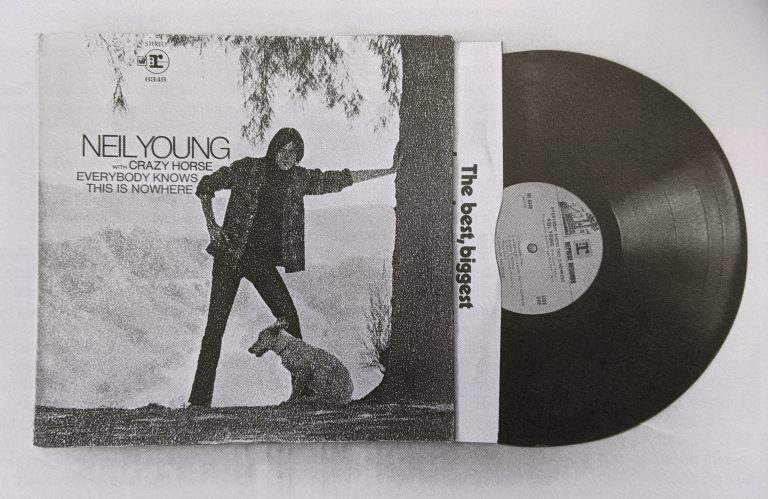

The standard tuning of a guitar is E, A, D, G, B, and E. One reason for this is related to the actual physical nature of the instrument – to its neck size and length. Each string is a different gauge and thickness, ascending from the low E to the high E. The pitch interval between each string in standard tuning allows a comfortable reach for the hand to construct and play between chords. A chord is like a colour in that it is a blend of different notes played in unison.

Nowadays tuning a guitar is made a great deal easier by the use of electronic tuners, but something may be lost here: the ear and listening. The electronic tuner reads the exact frequency vibration of a string running through the body of the guitar. The player can adjust each string accordingly. The electronic tuner gives a matter-of-fact calibration but, ironically, for a guitar to be in tune it must be slightly out of tune. This is called inharmonicity.

Tuning by ear is more refined to the nuances and microtones of pitch between each string. It emphasises the relational value between one string and another, like the contrast and effect of one colour against another. For example, how the D string might sound alongside the A string and G string in standard tuning. It gives a harmonious sound and creates a level of intimacy between the player and the sound. This method involves holding down and playing the fifth fret of the sixth string at the same time as the fifth string played open. The objective is to make both of these sound the same, to reach an equivalent and harmonious pitch on both strings. This is achieved by adjusting the tension on the fifth string until it, literally, slots into place. The sound of the opening string moves and wobbles until unison is found.

Karl Burke

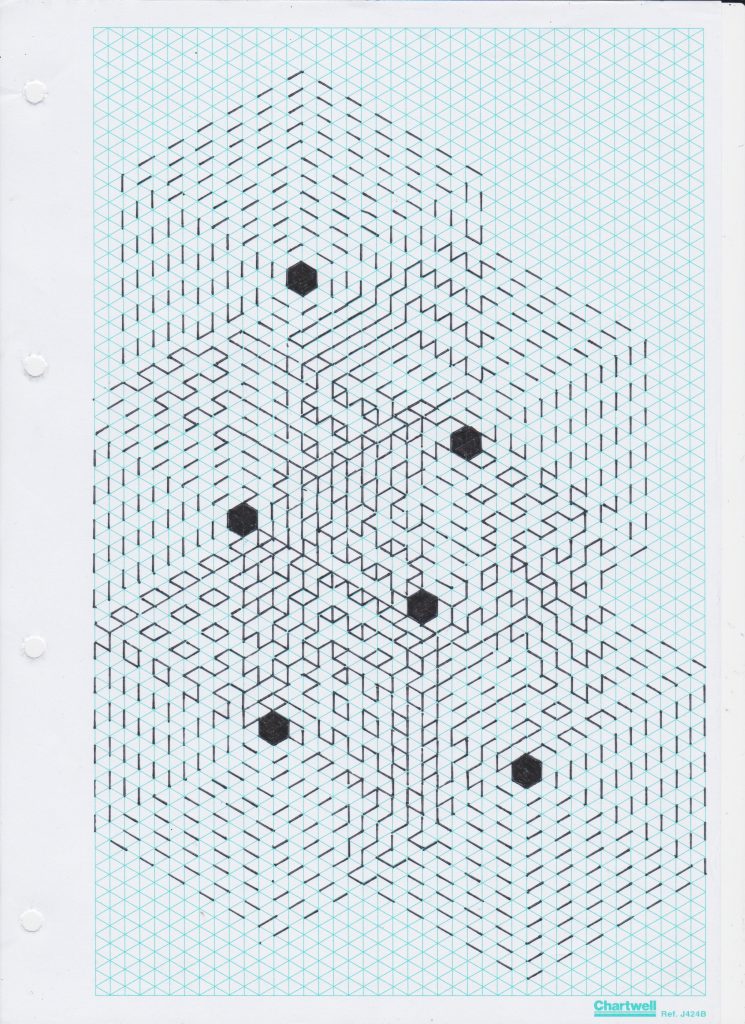

A visual representation: tuning a guitar, 2019

Ink on graph paper

This procedure is repeated on all strings with one exception: on the third and second strings where the fourth fret is held instead. This method of tuning is both simple and complex, requiring patience and time.

While considering my thoughts on the topic of tuning, I decided it would be a good idea to restring and tune my own acoustic guitar. It had been some time since I changed the strings and they were very dull in tone. I bought a new set of Martin guitar stings from a local music store and set about the process. Usually I would tune the newly strung guitar when all the new strings are roughly in place using the standard tuning to do so.

Straying from this format, however, I tuned the first string by ear and continued a relative yet intuitive tuning of each and all strings from that point. For a guitar to be in tune it must be in tune with itself; it is an ecosystem of relations. This is known simply as an alternative tuning method, a counter to standard tuning.

It’s as if I were moving objects around a room until through some subjective logic I land on an appealing sequence. Everything fits and is in agreement. This sequence is a reflection of the room, the spare room at home. The sound of the guitar fitted into the room, into the sonic resonance of the room; a thing placed in a room with extreme consideration.

I was curious what type of tuning I ended up with. Using the electronic tuner, I discovered it to be B, G-flat, B, B, G-flat, and B. The sound of space in a room.

I arrive by train and make my way to the gallery. It is a short distance, so I walk. VISUAL is a contemporary art gallery in County Carlow. I am showing a work there, one I first made in the Leitrim Sculpture Centre.

The gallery space I am showing in is large, with very high ceilings. To enter it, I need to ascend three steps. This means the space unfolds incrementally, revealing itself slowly like a mountain does to you when driving through a bend in the road. The ceiling space above is out of reach and hard to quantify. An expanse of concrete floor rolls out alongside a full-length window running on the right, through which one can see an external pool of water. The opposing concrete wall is shorter, running left to support another out-of-sight space.

The eight individual pieces that make up the work Taking a Line are already leaning against one of the concrete walls in the gallery space – a small silent crowd, waiting. Each piece is an open frame constructed with a mild steel bar measuring eight-foot square – not dissimilar to the stretcher of a canvas – with a horizontal bar running across its centre. All frames are painted matt black. The assembly of the work involves butting each frame against another at a right angle and securing them with cable ties. And repeat. Because of the modular nature of the work, there are numerous, if not endless, possible configurations. I have installed this sculpture many times in different galleries in a range of spatial configurations. I decide that this will be the last time, the last one.

I am slow to proceed. I need to acclimatise to the space. To walk around, to move in it, through it. To know it. To weigh the air wrapped up by the floor, walls and ceiling, concrete and glass.

I try to think of space as a thing. Not just the substrate that frames the sculptural thing but as a piece of sculpture in its own right. A thing in the same way we consider the material world around us: wood, stone, and steel. Space has volume, weight, and mass. Space has measurable dimensions: length, height, and width.

Unwrapping the work is a little tedious, yet it gives me more time to spend in the space.

I decide to create a diagonal line running across the gallery, to divide the room in two – wall to window, two zones. It comes together quickly, right angle upon right angle, like a snake weaving across a desert plane. I walk around the space. I leave and come back. I walk again, weaving over and back, looking on the work in its present position. The space pushes and pulls. The sculpture recoils. It seems out of harmony with the space, out of sync. I change the angle of orientation, and soon change it again.

My role here is to tune one to the other.

I latch on to a corner jutting out into the space and hinge the work out from that, right angle hugging right angle, same upon same. I continue assembling the work across the space towards the window. It creates a corridor between the work and the architecture.

Now each move is in millimetres. Millimetres feel more like kilometres.

The to-ing and fro-ing is exacting and measured. This encounter is a vibration, a fissure. The work sits into the space and the space holds it in mutual attunement.

Karl Burke is an artist and musician based in Dublin.

The main image: Karl Burke, Mound, 2011, digital photograph, courtesy of the artist.

This essay first appeared in PVA 11, Winter 2019.