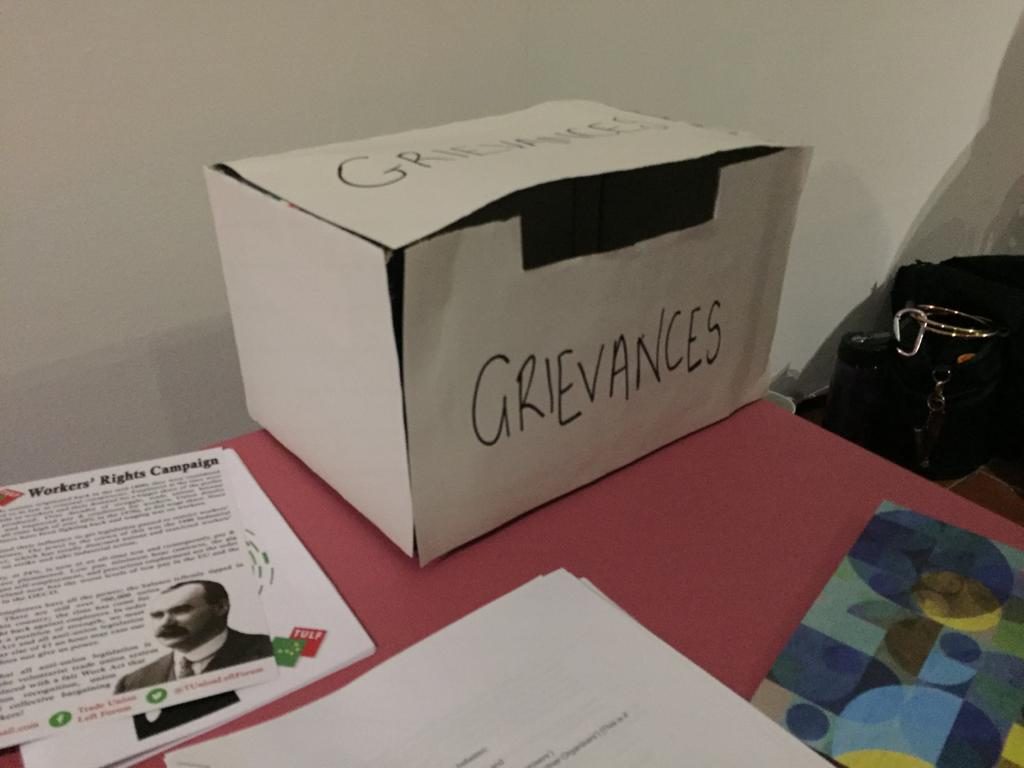

Photo courtesy of A4 Sounds

Chris Hayes: When and how was Praxis Artists’ Union founded? How did the early conversations and concerns unfold?

Kerry Guinan: Praxis Union came out of an artistic programme originally, which is quite interesting. It began in A4 Sounds as part of a multi-year programme titled ‘We Only Want the Earth’, named after a James Connolly poem. I facilitated a one-month experiment in February 2020 and here we are today. As part of the experiment, we wanted to ask whether a trade union model was missing in the arts and whether it was desirable – and feasible too. Ultimately, the group involved felt it was successful and we decided to continue building it into a permanent organisation. We just launched the union officially last month.

CH: In that early trial phase, what kinds of concerns were artists bringing up and how were you understanding or defining success in that context?

KG: Good question. It was a really exciting experiment because none of the group had previously met each other, and we came from distinctly different backgrounds and disparate disciplines, different parts of the country … all sorts of different motivations for taking part. Yet what struck me during that time, and now remains something I am aware of as Praxis continues, was how hard it was for us as a group to actually speak about our workplace issues to strangers – to fellow artists – because there’s such a fear around reputational risk or losing cultural capital or something. People hold workplace issues close to their chest or don’t even recognise these issues in their own lives.

Little of the work we do properly remunerates us, so we have very low standards for ourselves. It was really amazing – when we did start to open up about what was actually going on in our lives and the contracts that we had ongoing, actually this new type of knowledge began to emerge that I hadn’t read before in surveys or these types of forums. We were starting to see patterns of what issues were most important to the people in the room. I think a real benefit to the union model is to bring this stuff into the air and realise that it’s not an individual problem – it’s a problem that lots of artists are experiencing. It’s through these shared experiences that we can build solidarity with each other rather than seeing each other as competition.

CH: There’s loads there. I think for me, one of the most important gestures in creating a union is that it frames people’s practices in terms of solidarity. But before we get into that, I was just curious about how you were understanding the site of the ‘workplace’ or its boundaries and maybe the boundary of the responsibility that Praxis Union can strategically address?

KG: In the last year, trade unions have been very powerful in Ireland and have been a very active voice. A lot of the people who they’re representing are no longer based in a single shared workplace – they’re based at home. This creates a distributed network. Examples like Amazon point to the way the global market is going … there isn’t just a singular workplace in a set location, instead there is a set of relations that are perpetually shifting. What we’re wedded to in the trade union model is the idea of collective action up to and including the collective withdrawal of labour. We’ve seen similar struggles with delivery workers and other gig economy workers who also don’t have a common workplace. And so, yeah, that’s how we can begin to address the question.

CH: I am curious if there have been similar efforts to organise artists in Ireland or abroad that informed your thinking?

KG: To my knowledge in Ireland, there have been unions for different disciplines and there are still: there’s a musician’s union in Ireland and there is a theatre and film union also. We were also very inspired and got a lot of help from Community Action and Tenants Union, which is a new independent union set up for renters and communities in Ireland. Our members have been partially involved in other things like the Arts Black Out Campaign, we have been involved in Dublin Digital Radio, with A4 Sounds and Give Us the Night, so I think there were also organisations within Dublin and within Ireland that were really key, that were creating ecosystems in which this union could form.

CH: A union as an organisation, or unionising as a political strategy, has historically been understood with a focus on specific, discrete locations where labour can be withdrawn or other actions taken – the factory, for example, immediately comes to mind. While artists may have day jobs, their artistic work is spread across a number of diffuse organisations – the studio, the film set, a theatre, the gallery, local government, major institutions, the Arts Council, and so on. How does Praxis understand these distinct locales?

KG: It’s incredibly complicated. We do use the word ‘workplace’, but maybe it’s more useful to think about a set of relations. For example, I have been working from home for the past year but, depending on what hour it is in the day, I am working for different people. Sometimes I’m hiring other people, sometimes, you know, I’m on the opposite side of this. I may be in the one space, but the power dynamics within them change. It relates back to that classic idea of the means of production. Where are artists getting their money? And can we have more power in those particular situations?

There are conflicts around people who might be members as artists, but then who are also curators and also might hire other artists to do things. And in those circumstances, we have to just draw a line under that – we can only represent you within your capacity as an artist, and once you cross over to something else then we can’t represent you and we might even organise against you.

CH: I think registering that kind of complicated and often contradictory nature of contemporary artistic labour is critical – it’s something I am trying to achieve in this interview. This framing around a set of relationships that artists necessarily engage in is important, but I do also really appreciate that kind of return to clarity in some ways of just yeah, like the means of production. It just matters who’s getting paid, how, and when. It’s very complicated and also very simple.

KG: How am I gonna pay my rent?

CH: Exactly. So I suppose, just now that we’re kind of articulating what those relationships are, there’s a worthwhile distinction, I think, between organisations that may commission, exhibit, or offer other kinds of support to an artist – institutions that they depend on or negotiate with – and sites of production that an artist often pays for – such as the studio, a film set. There are many others that may overlap with the artist’s daily life to the utmost extent, such as other forms of welfare or employment, access to healthcare, childcare support, and so on. The nuance I am wondering about specifically is what kind of labour power does an artist hold in these areas and how it can be withheld.

Photo courtesy of A4 Sounds

KG: We’ve put it into our vision statement that we want to represent artists in their living and working conditions. So we recognise the whole lives of artists as being very messy and precarious and shape shifting. It’s not just about where they’ll get their money, but it is about things, like you mentioned, such as access to welfare support – access to housing is such a huge one. And we are currently working on issues with regard to artists with disabilities as well, and how best to triangulate issues of welfare and precarity. It has been interesting in the past year how often welfare has come up as an antagonist within artists’ lives. I suppose, most artists will eventually end up signing up to the dole or onto different schemes, and that can be a very aggressive place to be – especially in terms of how little these institutions actually understand what it is to be an artist.

So in terms of where we are drawing our power from, I think it goes back to collective labour. The power comes from us joining together rather than feeling isolated and atomised – dealing with these things by ourselves and thinking that it’s an individual problem. And the more we can come together and share our experiences of these issues, the more we can actually figure out how to change them, because then you can start to map patterns and places where it keeps coming up again and again.

I think boycotting might end up being a very strong tactic for us and our members. If there’s an organisation that’s treating artists poorly, we can call for our members to refuse to participate in that organisation in any way. There are also tactics such as working to the letter that are especially interesting for an arts context. Working to the letter means working exactly to the terms of your contract. It’s often the case the project fee doesn’t pay us the minimum wage. We would end up with a very different outcome if artists refused to work beyond what these small fees allow. That’s just one strategy. I think that’s a strength of Praxis Union as well … we do have this huge resource of creative energy, and we can think creatively around these types of tactics.

CH: I don’t know if you would describe it in these terms, but I had always understood your practice as an artist as not just being ‘about politics’ per se but invested in forms of action traditionally understood as political and motivated by a simultaneous effort to leverage that form for a strategic end. We first spoke when I interviewed you as an election candidate, and there’s your more recent Sell Nothing (2021) billboard series. Do you think that the kind of recent resurgence in activism and the increase in the number of organisations like Praxis Union will help shape how artists are producing work?

KG: Definitely. We want to both change the material conditions for artists, as well as change how people are thinking about these topics. I would be very curious to see what type of art would be produced if artists were all paid a living wage. There would be a huge difference in quality and also a lot more risk and experimentation. These questions aren’t separate. If you give people better resources, you’re going to end up with a much more vibrant artistic landscape. I’m hopeful that we can change things and that it will encourage artists to think about themselves as a community.

I think there’s something really humbling and positive for artists to put aside any differences – even creative differences – to recognise this shared experience of always being paid last and always being the most precarious worker within any kind of arts ecosystem. This is a common truth for all of us. So the real aim of the union is to build a community of solidarity, to build a strong arts community that recognises this shared experience. What we all want as artists is to produce better art. And also to be able to have a good life as well – to be able to pay rent and bills and live on top of that.

CH: Various people have commented on the neoliberal subjecthood that the contemporary artist is compelled to work within, particularly considering the precarity of employment, freelance contracts, and the hyper-branding of identity, etc. Efforts to introduce organising and collective action as a key activity for these workers seems particularly charged within this context. We had touched on it at the start of the conversation when you were talking about solidarity and care …

KG: What art production actually involves is a huge economy of favours. And so we talk about artists working alone – being competitive and self-driven – and you know, it’s true to a degree that these are the conditions that we’re in mostly. But it depends on the discipline, too, as filmmakers and theatre practitioners are more used to working together – maybe that’s why they are more likely to be in unions.

I bet if I asked any artist to consider over the last three months how many other artists they interacted with, how many did they help out or ask for help from … already, we can recognise this often-hidden ecosystem of artists assisting each other in their day to day lives. I’d be hopeful about structuring that type of solidarity within an organisation in which the members have complete ownership, where they can decide its direction.

CH: I really loved that phrase ‘economy of favours’; it’s a very evocative one. So that kind of leads into the second last question. How do other union efforts inform or shape the thinking within Praxis? I am thinking of recent efforts with Amazon and McDonald’s, for example, companies who are utilising precarity and dispersing workers to undermine organising efforts. Noticeably, we’re in this historical period where we’ve been talking about the decline of labour power for many, many, many decades now, but it feels like, potentially, things are changing or at least people aren’t willing to put up with it anymore, there’s a renewed urgency to this line of thinking …

KG: Yes, I think you’ve just raised something interesting about the decline of labour power. Personally, the places where I’ve been taking inspiration from for Praxis are all kind of based in the service economy – like Amazon, Deliveroo, Uber Eats, Fight for $15. What is driving this decline of labour power is this shift in the Global North away from industry towards service- and knowledge-based work, as well as the failure of unions to adapt to this shift. We are taking inspiration from others who are trying to organise around more gig-based or self-employed-based industries like Deliveroo and their strikes for better working conditions in Dublin.

Even though service labour is produced in different types of conditions and using different faculties of the body, the same type of exploitation and unequal power structures still exist. There are challenges due to the structure and forms of organisation – such as workers being made responsible for their own means of production, like with Deliveroo workers having to provide their own bikes. It’s very difficult to organise workers in this situation, as they’re isolated. Equally for artists, it’s difficult to speak out.

CH: And how have the efforts progressed so far? The professionalism of Praxis has been impressive from the onset, and there seems to have been a number of successful media appearances already.

KG: It’s going well, it’s going as well as we could have hoped. It was definitely a challenge trying to organise over the past year … like talking again about lack of shared spaces, a lot of us haven’t even been in the same room together. And now we’ve put together this union.

We met once a month over the last year and there was so much we worked on – pulling together a constitutional rulebook, getting legally formalised as a company, and now the public launch. We had our first AGM which fifty artists attended … that was really successful, there were really energetic conversations. I am really happy to have such amazing members from the get-go, all coming from different disciplines and different backgrounds. I’m also proud to say that we have solved several issues for artists over the past year, even before we launched officially, which I think again is a testament to the power of a union.

A month after launching, we have about one hundred active members. We’re planning another recruitment drive with a particular focus on artists in rural areas and those in Northern Ireland too. Eventually, we plan to join with another union at some point in order to get a negotiating license, because the government doesn’t like new unions – they haven’t given out a new negotiating license for a long time. So for us to be able to give our members legal protection – the limited legal protection trade union members have in Ireland – we will become a dedicated branch in another union. So, yeah, it will be a busy year ahead.

At the very first AGM, members overwhelmingly voted that the first thing they’d like to see a campaign on is to improve the funding procedures of the Arts Council of Ireland … and I’m not sure if I have to go and get into why these procedures are bad because I imagine everyone knows. What we’re asking is that the Arts Council commits to consulting with us as a union to improve their funding procedures. We’ll work very closely with our members on this, to identify the strengths and weaknesses and help redesign the system. So if artists want to have a voice in trying to reshape this really outdated, bureaucratic, and demanding system, then they should join the union. As of today, the Arts Council has agreed to a meeting with us next month – which is really positive news. We will stay with our campaigns until we reach some kind of solution with them. We are totally committed to this. We plan to be a winning union.

* For more information on Praxis Artist’s Union, see https://www.praxisunion.ie/.