He was eminently a man of his time – the top forty were much more important to him than Bach or Beethoven and he had an almost mediumistic sensitivity to the cryptanalysis of pop culture.

– Carl Andre on Robert Smithson

Something of the pungent, sulphurous, sweaty hum of the rock star came off Robert Smithson. His swagger recalled Jagger or Plant in their preening, absurd pomp, and something of his air suggested a teenage riot. He died in a plane crash aged only thirty-five, the same way others had famously gone: Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper in 1959, members of Lynryd Skynyrd in 1977, and guitarist Randy Rhoads in 1982.[1] This early death perhaps contributed to the mystique that has built up around Smithson in the decades since, as groups of fanboys and fangirls idolised him and obsessed over the details of his life and work. Considering Smithson as a rock star works not only because he looked like one but also because it throws up alternative ways of thinking about what he did and how he did it. It takes him out of art and puts him somewhere else.

The cover of his collected writings shows the now familiar black-and-white photograph by Gianfranco Gorgoni of Smithson on the newly constructed Spiral Jetty. Smithson strikes a nonchalant pose reflected in the Salt Lake. It could easily be the album cover or publicity shot for a country rock star in the early 1970s. With his clothes and attitude, Smithson cultivated what was already, at 6 foot 3 inches, an imposing presence. As Thomas Crow put it, ‘His lanky figure clad in the same black clothes for days on end, a thatch of thick dark hair, mineral dust embedded in his hands, he could seem a Gothic apparition in himself.’[2]

Courtesy of Atelier

Courtesy of Atelier

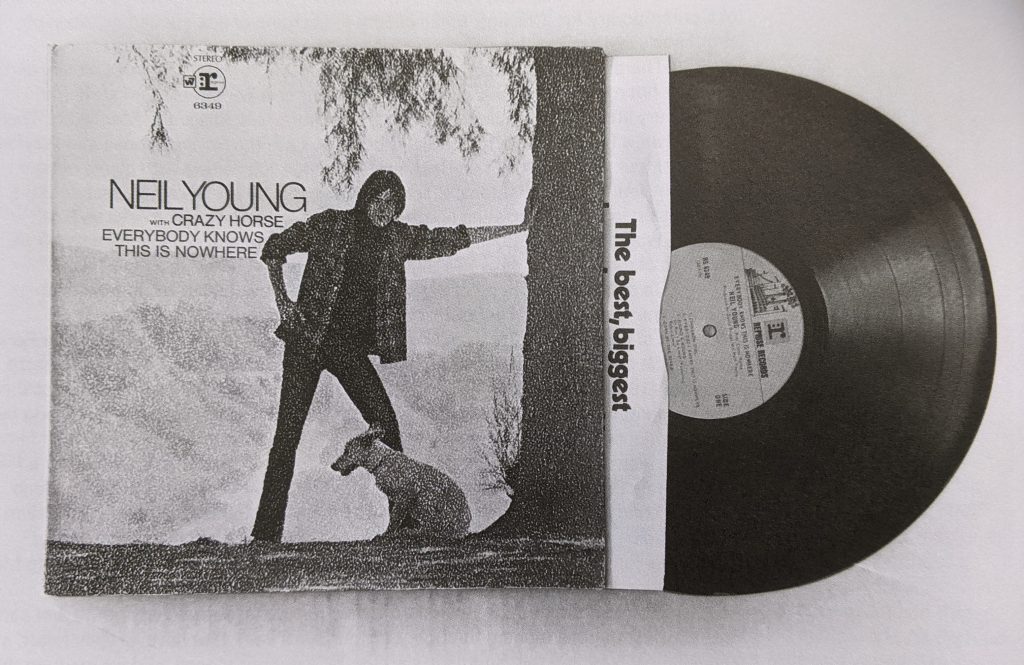

With long hair, black jacket, and jeans, his Gothic demeanour recalls the laidback outlaw attitude of Don Nix photographed in a field on the gatefold of Living by the Days (1971). The image also flirts with the rock-music trope of the landscape as the site of mystical revelation. You see this on the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy (1973), picturing the Giant’s Causeway; or on the double gatefold image on Neil Young’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969) in which Young poses legs akimbo leaning on a tree against the backdrop of the Californian mountains. Smithson owned both the Don Nix and Neil Young albums as well as Led Zeppelin IV, a record similarly steeped in rock mythology. His poems from the early 1960s share some of the stylistic mannerisms of rock lyrics. Consider the opening of ‘To the Eye of Blood’, for example, that, with its nod to William Blake, could have been torn straight from the Jim Morrison book of popular, cod-philosophical doggerel:

It is

As high as Heaven

What can we do?

What can we know?

Are they all dead?

Are they all dead?

In the tempest of hails

We seek.

In the destroying storm

We seek.

In the mighty waters overflowing

We seek.

When shall this scourge pass?

Upon

The line of confusion.

Upon

The stones of emptiness.

Behold:

For peace we had great bitterness.

A wind blow from Heaven.

A wind blows from Hell. [3]

The full inventory of Smithson’s library was published in 2004 in the catalogue for the Robert Smithson exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.[4] The books and magazines had already been catalogued and published,[5] revealing the extraordinary breadth and range of material that Smithson, an autodidact without a college education, had read. Topics represented include anthropology, aesthetics, science fiction, philosophy, geology, physics, biology, and travel. It is well known that Smithson’s erudition is reflected in the consistent themes found in his work. As Richard Serra recalled of their friendship: ‘Smithson’s concerns were wide and varied. They included entropy, crystallography, and archaeology and took in all kinds of literary and filmic references.’[6]

There are also books on the list that suggest some other concerns that may have been overlooked in favour of the well-worn art histories. The library includes classic texts from the cultural history of the psychedelic movement: Robert De Ropp’s quasi-academic history of drugs from 1957, Drugs and the Mind; and Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception (1954) in which he narrated a firsthand account of taking the hallucinogenic drug mescaline. This is the book from which, famously, the Doors took their name. But what was particularly remarkable about this 2004 catalogue was that it also included a list of his collection of over 250 records. There are a fair few pieces of classical music to be found there: Bach, Berg, Berio, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and so on are represented. So, too, is experimental music. There are albums by Varese; La Monte Young; Music from Mathematics with pioneering computer-generated music published by IBM; and Art by Telephone (1969) published alongside an exhibition by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, that included a recording of a telephone dictation of Smithson’s instructions for a non-site piece for the show.

There is not a lot of pop. Some Beatles, Beach Boys, a Joni James album, and a few ’50s hot-rod compilations, but there’s no bobby soxer or bubblegum stuff. And there’s very little kitsch either, except albums from Mrs. Miller and Mantovani. There is, however, a fair bit of rock music: five albums by both the Rolling Stones and Waylon Jennings; four apiece by Captain Beefheart and Elton John along with plenty of hard rock from Jimi Hendrix, Santana, Black Oak Arkansas, Blood, Sweat & Tears, and the like. This opens up a fascinating line of speculation as to how listening, as well as reading, worked its way into his practice and what it means to consider Smithson via the logic of rock.

To do so requires a bit of digging as there are few sustained references to popular music to be found in Smithson’s work. The Grateful Dead is quoted in ‘A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art’. There are also mentions of Van Dyke Parks’s Song Cycle and Captain Beefheart in the essays ‘A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects’ (1968) and ‘A Cinematic Atopia’ (1971), but they are fleeting. The unpublished ‘The Lamentations of the Paroxysmal Artist’ opens with a reference to ‘a song sung by Dion ‘pronounced “Deeon”, to rhyme with neon’.[7] And in the initial treatments for films there are instructions to use the music of Vanilla Fudge in Monument: Outline for a Film and Captain Beefheart in Movie Treatment for Tropical Cargo. In the 1968 film Mono Lake (finished by Nancy Holt in 2004), Smithson wears cowboy boots and ten-gallon hat while a radio plays ‘Stop the World (and ‘Let Me Off’) by the outlaw country singer Waylon Jennings. Smithson and Holt had stopped off in Las Vegas on their way to Mono Lake, California, to catch a Jennings concert.

A similar dig through the record crates throws up some dusty gems that can also suggest themes running throughout Smithson’s work that have, at their heart, a sensibility of rock and roll. Smithson’s anti-establishment stance, and his attitude that ‘the Establishment is a nightmare from which [he’s] trying to awake’ can in fact be reverse engineered into his earthworks and non-sites as objects that kick against the pricks of the institutional structures of art.[8] Similar fuck-you attitudes have been the familiar riffs of rock and roll since its inception, for instance, with the likes of Little Richard whose debut, Here’s Little Richard (1957), Smithson owned. He also listened to Alice Cooper’s Killer (1971) and Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut (1970), which offered a more contemporary update of theatrical ‘shock-rock’.

An argument could be made that the chaos and excess of rock and roll was an expression of the same preoccupation with entropy that became the dominant leitmotif in Smithson’s work. There are three albums by Vanilla Fudge in Smithson’s library: Vanilla Fudge (1967), Renaissance (1968), and The Beat Goes On (1968). The latter is an almost unlistenable mixture of pastiche, noise, and sound collage that avoids any conventional songs. The band were best known for playing covers of soul and pop songs (most famously the Supremes’ ‘You Keep Me Hanging On’) in a feedback-laden heavy-rock style that was always threatening to implode under the weight of its own metals. Experiments with the Dionysian effects of feedback, noise, and sonic chaos are also represented in Smithson’s collection by Hendrix’s Are You Experienced (1967) and the Velvet Underground’s most extreme album, White Light/White Heat (1968), which culminates in the near twenty-minute cacophonous paean to drugs, violence, and perversion, ‘Sister Ray’. This is music that, like Smithson’s aspirations for his sculptures, seems to emerge from systems that were only barely held together and were teetering on the brink of chaos and collapse.

Smithson was clearly a drinker, carouser, and lover of the rock-and-roll lifestyle. He frequently held court in the nightclub Max’s Kansas City, a focal point for New York countercultural nightlife where artists and musicians rubbed up against one another.[9] Carl Andre was there: ‘Many a night we lucubrated drunkenly in the stews of Max’s. Bob’s capacity for Budweiser beer was beyond description or belief – he would be tipsy for hours but only rarely if ever soused.’[10] As curator Kynaston McShine remembers: ‘Warhol was in that scene. Carl Andre was part of it, Janis Joplin was there, Waylon Jennings was there, all the people who would come out at two in the morning were there. Night freaks.’ [11]

The freak in Smithson is hinted at in his batshit weird drawings from the early 1960s. These were not so well known until Pop, the 2016 exhibition at James Cohan, brought them together. There is a lot of sexualised imagery in these early works that flirts with homoerotic and fetishist themes. Pencil drawings of naked men and women might have been copied from contemporary skin mags, B movies, and comics, and there are men in leather boots and caps, sometimes wrestling. However camp or kitsch this imagery first appears, it is also freighted with the sexual ambivalence and ‘deviance’ that made groups like the Rolling Stones and Jagger’s dress at Hyde Park in 1969 so threatening and anti-establishment at the time. The Velvet Underground, after all, were named after Michael Leigh’s somewhat trashy book exposing ‘aberrant’ sexual practices like BDSM and group sex in suburbia in an attempt, as the cover puts it, to ‘shock and amaze’ the readers.

Given his early death, we can never know whether Smithson would return to such sexual themes and motifs. There is, though, this strange passage in ‘The Monuments of Passaic New Jersey’ essay that hints at a possible queer reading of Smithson that can only be alluded to here: ‘The great pipe was in some enigmatic way connected with the infernal fountain. It was as though the pipe was secretly sodomizing some hidden technological orifice, and causing a monstrous sexual organ (the fountain) to have an orgasm. A psychoanalyst might say that the landscape displayed ‘homosexual tendencies’, but I will not draw such a crass anthropomorphic conclusion. I will merely say, “It was there.”’[12]

The freaky or queer Smithson also finds expression in records by Elton John, Little Richard, Alice Cooper, and David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972). Each of these performers created alter egos that were gender fluid and performed their sexual ambiguity within the arena of rock and roll. Smithson performed a little too. In his first video work, made with Nancy Holt, East Coast, West Coast (1969), a staged conversation takes place between him and Holt. She plays the part of a buttoned-down, East Coast conceptual artist while Smithson that of the lackadaisical, intuitive, ‘free’ West Coaster. It includes the following exchange:

Smithson: I get about four hits a day … I really just like spin out on acid. I have my thing going. I don’t care about the system … I did a sunshine piece. I measured sun grams and wrote them down. But I … I … I’m interested in, like, just working. I don’t care about all that system stuff, all this other stuff. I am out there doing it, I’m doing it!

Holt: Well, you know that’s a philosophy too … You’re a pragmatist. Yes, you’re some kind of mystical pragmatist.

S: Nahhhh …

H: And you have to define yourself better …

S: Definitions are for really uptight types … don’t lay that on me, man.[13]

While this laid-back, hippy artist is a performance at odds with Smithson’s usual persona, there was something performative about that usual identity too; from the cowboy boots that he frequently wore, such as in the documentation from Mexico for Yucatan Mirror Displacements (1–9) (1969), to the antagonistic, abrasive, and ‘Gothic’ personality that the kid from New Jersey adopted after reaching New York. Carter Ratcliffe recalls Smithson at the time of his involvement with Artforum at the end of the ’60s: ‘I remember Ivan [Karp] talking with nostalgia about the terrible behaviour of everyone in the ’50s. His word for it was “Gothic”. Later on, Smithson and Richard Serra and a few others were the only ones keeping that “Gothic” tradition alive. In the Artforum day, the art world was getting very professional and fairly decorous.’[14] When Smithson’s persona is considered in terms of its performative dimensions, it invites comparison with other personas created and performed by American artists such as Jackson Pollock, the all-American, James Dean–style, denim-clad heartthrob star of Hans Namuth’s photographs, or Warhol’s swish, blank superstar. It also suggests a performativity that further underwrites his ongoing opposition to the idiosyncratic critique of the ‘theatricality’ of Minimalism by Michael Fried, whom Smithson witheringly dismissed as a ‘fanatical puritan’.[15]

Fried’s problem with the theatricality of Minimalism was that it disrupted the viewer’s ‘absorption’ in the artwork, diverting aesthetic attention towards the time and space within which those works of art sat. This was a problem for Fried because ‘art degenerates as it approaches the condition of theatre’, creating the troublesome ‘illusion that the barriers between the arts are in the process of crumbling’.[16] While for Fried the analogue for this disruption and temporal immersion was the idea of the theatre, it finds another analogue in the crumbling of phenomenological barriers in the multisensory experience of psychedelia. The term ‘psychedelic’ was coined in 1956 by the LSD researcher Humphry Osmond to mean ‘soul manifesting’, that is, an activation of consciousness. Although virtually synonymous with hallucinogenic, psychedelic implies that the drug or experience acts as a catalyst to further feelings and thoughts, and is not merely hallucinatory.[17] There is no doubt that Smithson was influenced by psychedelic culture. John Baldessari recalls tripping with him: ‘At that time even I tried mescaline, you know. I remember taking mescaline with Bob Smithson and Tony Shafrazi and walking around West Broadway and Canal and just laughing our heads off. And Bob drank. We all drank enormous amounts.’[18] From Smithson’s records, Country Joe and the Fish’s Electric Music for the Mind and Body (1967) – an album created with the specific intention to accompany an LSD trip – encapsulates psychedelic culture. This was music made by people taking drugs to make music to take drugs to.

There is a dual significance of psychedelic culture to Smithson’s work. On the one hand, it was a manifestation of the anti-establishment counterculture that he was also exploring in the field of art and which informed his choices of music. On the other hand, it focused attention on a multisensory experience that expanded attention onto the aesthetics of the whole body. In other words, psychedelics prompted a new way of thinking about aesthetics, and hence art; a way that was not restricted to eyesight alone. It suggested a route out of what had become the dead end of modernist painting and its preoccupation with formal experiments into flatness. As Dave Hickey puts it:

Psychedelics, I think, disconnect both the signifier and the signified from their purported referents in the phenomenal world – simultaneously bestowing upon us a visceral insight into the cultural mechanics of language, and a terrifying inference of the tumultuous nature that swirls beyond it. In my own experience it always seemed as if language was a tablecloth positioned neatly upon the table of phenomenal nature until some celestial busboy suddenly shook it out, fluttering and floating it, and letting it fall back upon the world in not quite the same position as before – thereby giving me a vertiginous glimpse into the abyss that divides the world from our knowing of it.[19]

In his ‘Spiral Jetty’ essay, Smithson refers to his sculpture as a ‘“spiral ear” because it suggests both a visual and an aural scale, in other words, it indicates a sense of scale that resonates in the eye and the ear at the same time’.[20] In doing so Smithson shows an awareness of the elective affinities between aural and visual registers, resonating with the blurring of such boundaries that was characteristic of psychedelic experiences. Psychedelia provided a way out of modernism because it prompted a new way to think about the senses as being interconnected and inseparable. Its value was that it did not come weighed down by the baggage of either preexisting art-historical narratives or expectations of political revolution inherited from the historical avant-garde.

In some respects, Smithson was an outlier in the art world of New York. Apart from some short general classes at the Art Students League of New York and the Brooklyn Museum School, he was mostly self-taught, and did not undertake the BA or MFA training that would have grounded his work in debates about painting and sculpture and the legacies of European modernism. This is reflected in his art, which does not, in general, concern itself with the familiar double injunction of coming to terms with either the problems of abstraction in painting or negotiating the legacy of the readymade and Conceptualism. Such a condition is exemplified by Donald Judd. Smithson was troubled by neither Greenberg nor Duchamp and was often dismissive of both. As a result he was free to explore a different trajectory for contemporary art framed by questions of affect and entropy that we are still coming to terms with. He was able to do this because Smithson came of age artistically at the same moment the wave of alternative popular culture crested and broke. His art emerged from the same milieu as the rock music he collected and the same values, themes, and motifs can be found sedimented within their respective spiral scratches.

* This essay first appeared in PVA 11, which focused on music, and was published in 2019. More info on the printed journal can be found here.

Notes

[1] Famously Waylon Jennings was due to be on the same flight as Holly and when Holly said to him, ‘Well I hope your ol’ bus freezes up,’ Jennings joked: ‘Well I hope your ol’ plane crashes.’ There seems to be evidence that Smithson and Jennings knew one another through hanging out at Max’s Kansas City, New York.

[2] Thomas Crow, ‘Cosmic Exile: Prophetic Turns in the Life and Art of Robert Smithson’, in Robert Smithson, ed. Eugenie Tsai with Cornelia Butler (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 34.

[3] Robert Smithson, The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkley: University of California Press, 1996), 318.

[4] Organised by Eugenie Tsai with Cornelia Butler (2004).

[5] In Anne Reynolds, Robert Smithson, Learning from New Jersey (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 297–345.

[6] Robert Smithson, ‘A Conversation about Work with Richard Serra’, in Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years, ed. Kynaston McShine and Lynne Cooke (New York: MoMA, 2007), 26.

[7] A reference to the doo-wop song Dion & The Belmonts, ‘Somebody Nobody Wants’ (1961). Smithson, Collected Writings, 319.

[8] Smithson, 97.

[9] Lucy Lippard: ‘He loved conversation – he’d go to Max’s Kansas City every night with a conversation to throw out to the wolves.’

[10] Carl Andre, ‘Robert Smithson: He Always Reminded us of the Questions We Ought to Have Asked Ourselves’, in Carl Andre, Cuts: Texts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 252.

[11] McShine, ‘A Conversation about Work with Richard Serra’, 22.

[12] Smithson, Collected Writings, 71.

[13] Cited in Eve Meltzer, Systems We Have Loved (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 140.

[14] Amy Newman, Challenging Art: Artforum 1962–1974 (New York: Soho Press, 2000), 254.

[15] Smithson, ‘Letter to the Editor’, Collected Writings, 66.

[16] Michael Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood’, in Art in Theory 1900–1990, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Woods (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), 831.

[17] ‘Osmond originally sought a word in 1957 to replace “psychotomimetic” with one which would be “euphonious” and not connote a sick mind but expand and open the mind to man’s own nature to increase his understanding and awareness. He indicated that specific beneficial goals could be reached by “unhabitual preception’ through psychedelic drugs.”’ G. R. Nakamura and N. Adler, ‘Pyshotoxic or Psychedelic?’, Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science 63, no. 3 (1972): 416.

[18] Newman, Challenging Art, 253.

[19] Dave Hickey, Air Guitar (Los Angeles: Art Issues Press, 1997), 95.

[20] Smithson, ‘Spiral Jetty’, Collected Writings, 147.