In April 2017, I went to the Solstice Arts Centre in Navan in County Meath to view the National College of Art and Design MFA Interim Show, Detached. One artwork caught my attention.

It consisted of two artefacts and had an enigmatic catalogue listing:

Artist: Anaïs Wenger

Title: Remains of Kilcolman Castle, ou la sainte assurance de l’instant present, Part III

Medium: No Pictures Walk

Price: Travel expenses

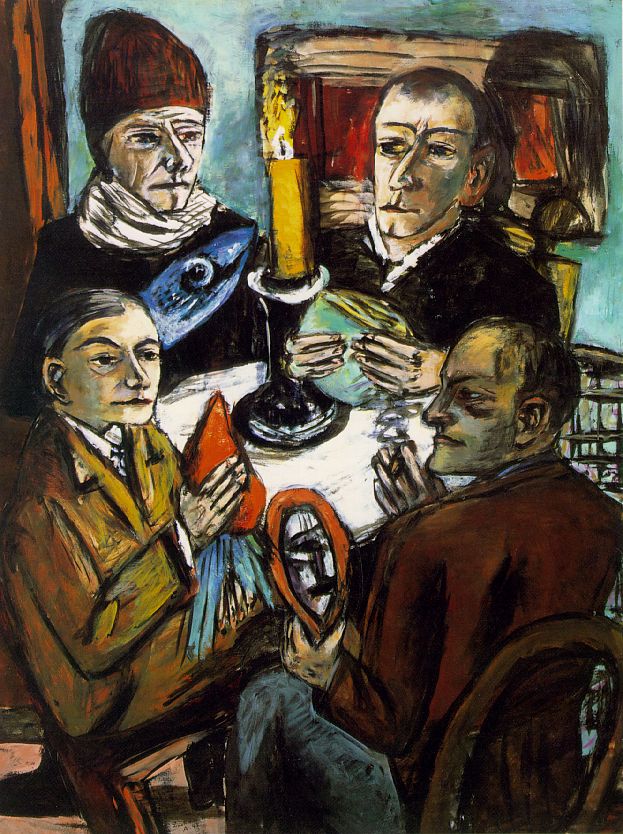

Anaïs Wenger

Anaïs Wenger

Detail of Remains of Kilcolman Castle ou la sainte assurance de l’instant présent

Photo: Florent Meng

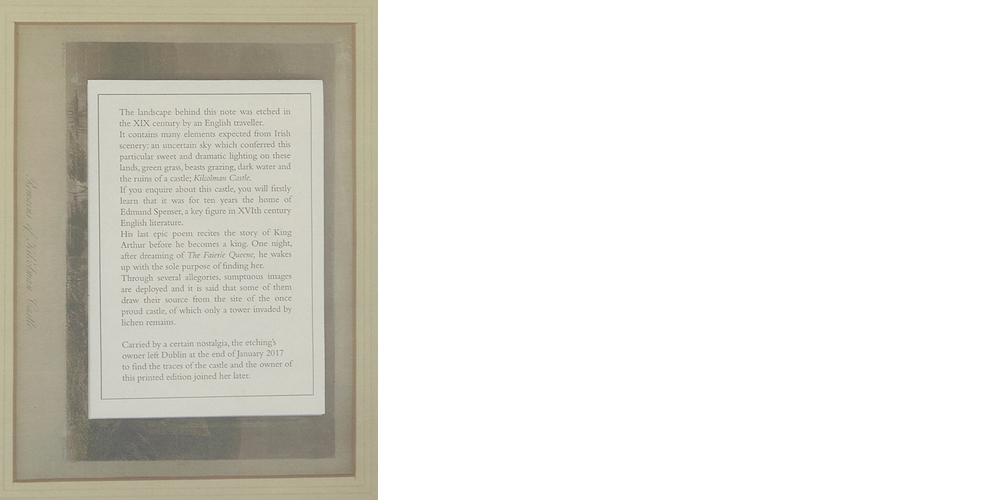

One of the artefacts was a framed Victorian-era etching of Kilcolman Castle, in Co. Cork. The image of the castle itself was obscured however by a rectangle of white paper containing a text written by the artist, Anaïs. The full text, on the etching, told how Kilcolman Castle had been ‘for ten years the home of Edmund Spenser, key figure in XVIth Century English Literature’. Beside this framed etching was another artefact, a printed reproduction of the first. The text in this version varied from the one on the etching. It contained the evocative words:

Carried by a certain nostalgia, the etching’s owner left Dublin at the end of January 2017 to find the traces of the Castle and the owner of this printed version joined her later.

A note on the wall of the gallery further stated:

In order to become the keeper of this print, please contact the artist by April 5th to take part in the next No Pictures Walk.

Because I love walking and the notion of an expedition into the unknown captured by imagination, I got speaking with Anaïs, a Swiss artist on an Erasmus year in Dublin, and I agreed to purchase the artwork, to participate in the performance, and to go on the next No Pictures Walk. Thus, in the coming weeks, Anaïs and I corresponded so as to arrange a date to travel, finally fixing on the 17th April, Easter Monday 2017. That will be the day of the No Pictures Walk.

14 April 2017

My friend Jer, a translator of French and other languages, translates the French part of the title of the artwork for me. This title, which has intrigued me since I read it, now reads in full:

Remains of Kilcolman Castle, or the holy consolation of the present moment

This idea brings up the thinking underpinning her concept: which is to remove the visual from the equation as much as possible. The No Pictures Walk itself has as a main component a verbal narrative after all, which takes precedence over the visual, while the image of the castle in the print has itself been removed, blocked out as it is by the rectangle of paper containing the text.

There is, too, a further prohibition to images surrounding the Walk: while we will be witnesses to the Castle, Anaïs wants this to occur without the distraction or mediation of taking photographs, she wants any images kept of the experience to be those recalled in memory, rendered in the mind’s eye.

For as she puts it in her artist’s statement:

Democratic access to images and information inaugurated through technical reproducibility […] has led to the standardisation of our innate perceptions.

Or as she put it more simply in relation to what I would have after the Walk: ‘You are gaining memories.’

18 April 2017

(One day after the agreed date for the No Pictures Walk).

The trip to see Kilcolman Castle has been postponed and there is no word yet from Anaïs to make new arrangements.

28 April 2017

Anaïs emails me with details of a new approach to the No Pictures Walk: she wishes to go to one of the libraries in Trinity College Dublin to see an old edition of The Fairie Queen, the epic poem written by Edmund Spenser, one-time occupant of Kilcolman Castle. I am puzzled by this, but intrigued also, so I agree.

30 April 2017

Anaïs writes saying that she would like to meet on Monday 8th of May for the No Pictures Walk; I mark it in my diary.

07 May 2017

The day before the walk, having not heard from Anaïs, I email her asking about travel arrangements. I expect to be told to meet in Heuston train station or Busáras bus station; I still have a vague hope, despite the mention of Trinity library, that we will, in fact, be going to Co. Cork to see Kilcolman Castle, but Anaïs replies confirming we are to meet at Trinity and asks if I have a valid library card.

This is disappointing, because by my bed lies a pile of walking gear I had set aside for the next day’s trip to Kilcolman Castle, all now suddenly made redundant. I realise I will have to go to the Castle by myself, soon, so as to complete the journey that had started in Navan, when I first saw the print and heard about the No Pictures Walk.

08 May 2017

10 a.m.: I meet Anaïs at the main gate of Trinity College under the blue clock. She is in her early twenties, tall, thin, with dark shoulder-length hair and fair skin. We go to the library entrance in the Arts Building from where we are directed to the Berkeley Library.

We arrive in the Early Printed Books section, accessed through a tunnel and then a lift up several floors to its main reading room. There we request a 1609 edition of Spenser’s Fairie Queen; it will take ninety minutes to retrieve from storage. We leave, descend a spiral staircase, and go and photocopy the record of the book as it appears in a print-out from Trinity’s eighteenth-century catalogue:

The fairie qveen, disposed into XII bookes, fashioning twelue morall vertues.

Lond.1609 fol. Press B.4.2.No.I.

[car.tit.& imperf. ad fin.] v.ee.I.No.I.

[The 4th, 5th, and 6th books of the latter copy are preceded by a title-page entit. The second part of the Faerie Queene, Lond. 1612. Some leaves introductory to the Faery queen are misplaced at the end of the volume.]

While we do this, Anaïs gives me my print of the framed etching of Kilcolman Castle with its obscuring text. As we walk down Nassau Street and up Kildare Street, we talk about her thesis, the first chapter of which is about a woman who showed her the way to Kilcolman Castle, and the second chapter of which is about a writer: me.

We go to the National Library of Ireland on Kildare Street and look up other editions of Spenser. The oldest is an 1868 edition, which requires an Early Manuscript Collection request; it will be available, in another annex of the Library, at 2 p.m.

Over coffee in a nearby café, I hear more from Anaïs about Spenser’s relationship to Ireland. The landscape of the area around Kilcolman Castle influenced the landscapes of his epic poem The Fairie Queen. Also, he wrote a book about Ireland that he sent to the Queen of England; legend has it that the locals, angered by the critical contents of this book, burned down Spenser’s castle in revenge, killing his infant son in the conflagration. Anaïs talks of the ‘power of images erased by words’ – how Spenser’s words led to the destruction of his Castle.

She notices I am taking notes in an A5 hardback bound notebook, and we talk about my writing this essay; I ask her does she mind, and she replies, ‘No, I don’t mind. I am just curious why you are doing it.’

It seems superfluous to me to have to explain why; it is like being asked to explain why I write at all. Nevertheless I give her various explanations, that the Walk captures my imagination, and also is a way of taking a break from the book I have been working on, which I am finding challenging. The Walk is a welcome diversion and break from that, and writing the essay also. Significantly too, it is relaxing to work on short form writing while in the midst of a longer project.

I ask her is it alright that I am writing about the Walk, about her.

‘I don’t want to feel used,’ she replies.

This makes me reflect; it’s possible this essay will never be completed nor published. However, if it is, the fact is, it does contain reference to her emails, our private correspondence, for example, and she may not approve of this. To reassure her I tell her I will send her the completed essay before I seek to get it published. But I feel a slight unease about the writing now, about the writing here.

12 p.m: We return to Early Printed Books section in TCD and it occurs to me again that this is not what I had wanted for this day: I had wanted to be outdoors. Nonetheless, it is a walk, and, because I love books and libraries, I am beginning to warm to it. So I open up another early edition of The Faerie Queen.

This is a 1609 edition that Anaïs and I admire a while, carefully turning its thick folio pages and scrutinising its blocky type to read Spenser’s words. Then we descend the spiral staircase again and head back to the traffic and pedestrian-clogged sunny streets to another library Anaïs has discovered in her research: The Royal Irish Academy Library on Dawson Street. This one is new to me. Housed in a Georgian building, it is contained in one book-lined room, with rows of tables with lamps for reading by.

Here we pore over another of Spenser’s books, written in 1596: A View of the State of Ireland, but this in an edition from 1763, the oldest Anaïs could track down.

‘It is over this text they burned down his castle,’ she tells me as she considers it. More than just a book then; a building block in the narrative of Spenser rather, and of Kilcolman Castle itself: A View of the State of Ireland as it was in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, written by way of a dialogue between Eudoxus and Ireneus.

I leave Anaïs at her desk reading these editions for a while then go browse around the bookshelves.

I’m delighted to find a copy of The Shell Guide to Ireland (1989) by Lord Killanin and Michael V. Duignan in the edition revised and updated by Peter Harbison – a modern classic that in an earlier edition was on the bookshelves of my childhood home. It was one of my father’s favourite and most referred to books.

This edition is an inch thick and about the size of an A4 pad, with a shiny cover showing a colour photograph of a megalithic site above a majestic valley and lake. Inside, on gloss stock, is an alphabetical listing, by geographical place and region, of archaeological sites and buildings of historical interest in Ireland, illustrated with line drawings, maps, and both colour and black-and-white photographs. These detailed entries make amateur archaeology possible for any enthusiast, such as, in the distant past, my father.

I find a reference to Kilcolman Castle: a description of the Castle’s location is given, along with an explanation of its connection to Edmund Spenser, and reference to the fact that at least part of The Faerie Queen was written there. The entry gives more context to this No Pictures Walk, but the book is also a source of nostalgia, connecting me as it does with my father who used it to research and visit antiquities with me and the rest of my family when I was young.

Anaïs and I break for lunch and afterwards return to the Early Manuscript Collection of the National Library, at the end of Kildare Street. In a small reading room we are presented with our requested books.

The Chandos Classics

The Faery Queen

By

Edmund Spenser

Edited from the best editions

With memoir, notes, and commentary

‘Those melodious bursts that fill the spacious times of Great Elizabeth that echo still.’ – Tennyson.

London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co. 1888.

In the ‘memoir’ included in this edition I read:

In 1597 [Spenser] returned to his home [in Kilcolman Castle], now blessed with children, where he dwelt, probably in peace and happiness, till 1598 when the Great Queen, no longer forgetful of him, wrote to the Irish Government, September 30 1598, recommending him to be made Sherriff of Cork. Alas! Life had brightened only at its close. In the following October the rebellion of Tyrone broke out with great fury. The English residents in Munster were doomed to destruction. The rebels attacked Kilcolman, of course. What right had an Englishman to a home of the Desmonds? The home was set on fire. Happily, Spenser, his wife, and two children escaped; but it is said that his infant, left behind by some accident, perished in the flames.

Spenser returned to England a ruined, heart-broken man … [and] did not survive the shock of this terrible calamity. He … died on the January following … and was buried, by his own desire, in Westminster Abbey … His pall was borne by poets.

Touched by this account, which gives a more elaborate version of the burning of the Castle, I no longer miss being outdoors on the walk to Kilcolman. I am content to be reading compelling accounts of a fascinating story, and handling beautiful editions of rare books.

Anaïs and I leave, and walk up to Thomas Street: she is returning to NCAD, and I am returning home a little further along in Kilmainham.

We stop.

The No Pictures Walk is over.

When I offer to pay, Anaïs informs me that the memory is the payment; there is nothing else to pay. She heads off to college to write up her notes; I go and look for a frame for the print in the antique and charity shops of Francis Street.

The No Pictures Walk is complete, and yet in a way it hasn’t taken place for me. I still think I should go to the Castle, ideally in the company of the artist. But Anaïs is returning to Switzerland in two weeks. She still would prefer that the castle occupy a place in her imagination only, be an image formed by the one glimpse she had of it, by the words used to describe it in books and by the representation in the etching – the representation I have never seen as it is obscured by the page of text she wrote.

Therefore, to complete the No Pictures Walk, I will have to go to Kilcolman Castle myself; now I just need to arrange when and how to do so.

June–July 2017

No progress is made on arranging the trip to Kilcolman Castle; I don’t have the time free to go away for the couple of days required to properly visit, nor even attempt it as a day-trip.

Then I see a possibility to do so during August. I will, at the invitation of my girlfriend, be going to Fermoy, Co. Cork, where she is from. Fermoy is not too far from Doneraile. I will be able then to finally take the opportunity to visit Kilcolman Castle.

Further, I decide I will borrow Jer’s camera, a decent DSLR, and in deliberate contradiction of the spirit of the No Pictures Walk, I will make a photographic record of the journey, of the destination, of the Castle. A part of me wants to keep some record for posterity in visual form, not trusting words or memory enough to be able to do so adequately without.

But my relationship with cameras has always been problematic. My father, the amateur archaeologist, was also an amateur artist. He did not consider photography to be an art form however, did not take it seriously, dismissed it. As an artist, he was good at looking at things, and regarded drawing as being the ultimate art form, the observation required for drawing to be true looking.

Looking through a camera, taking a photograph, he regarded as an inferior and poor substitute to this pure form of looking.

So it was that when I was a child he disapproved of me using cameras, and I have never lost this unease at this childhood prohibition.

When, aged eleven, I returned home proudly brandishing an ancient Pentax SLR I had bought at the local flea market, he looked at it, and me, disparagingly, and dismissed off-hand my newfound enthusiasm for taking photographs. He, after all, was truly good at looking at things, at what he sketched. My looking through this camera could not compare. Photography was not ‘real art’, or looking, it was lazy and a cheat somehow; not to mention the further prohibition that was at play, the one dictating that I should not take over his interest in the visual at all, but rather focus on the written. He would be the artist, I the writer: so I should take no pictures.

This childhood psycho-drama, full of Freudian undertones as it was, and is, has condemned my use of cameras ever since, the prohibition sitting in me, never shifting. Much as I have over the years attempted to rekindle my childhood interest in photography, that patriarchal banning of the practice has left an indelible mark on my psyche; like my father, at some deep level I too must believe that taking photographs is not real looking, is a cheat and lazy, and a poor substitute for proper looking- and that further, as a writer, I should not be taking pictures in the first place, but rather recording my experiences in words.

All this psychological baggage is carried by me when I borrow Jer’s DSLR and bring it with me on my trip to Kilcolman Castle.

25 August 2017

At the end of summer, I sit and compose an email to Anaïs who I have not corresponded with since June 20th. For days I have been struggling to write of my experience from a few days before, and apart from some abstract notes, this will be my first attempt to put down in an orderly fashion my account of the journey I finally took to Kilcolman Castle, where, in the less than half an hour spent on the site, I took almost 150 photographs, clearly breaking the No Pictures Walk ethos.

Before writing the email I consider the notes that I have put together so as to order my thoughts after the journey:

Having a camera, as Anaïs could have told me, affects me and infects the experience of the journey to the Castle. There is less immediacy, purity of experience, as an imperative to document the journey in pictures, not words or memory, strangely grips me.

But it is impossible not to want to take photographs, as if not only in defiance of the No Pictures Walk rule, but to prove and record I have been there; unlike Anaïs, I do not fully trust my memory alone to be able to evoke the experience ever after.

I email Anaïs at 6 a.m. on the 25th of August. This missive completes the No Pictures Walk:

I went, on Monday 21st August, to Kilcolman Castle. I am still thinking about how to write about it, maybe I will now (later). I took some photographs, do you wish to see some or not?

Kilcolman Castle is located beside a very atmospheric bog, in a field with some small trees. I was with my girlfriend who drove me and we had to cross over three fences (two of which were electric) and lots of cow dung.

The castle itself is really just a remnant, it did not seem like a complete structure, there was a short tower bit and a bit sticking out with possibly a platform on top. It is possibly, probably, made of granite.

We went on a rainy day, overcast, but it did not rain too much. There were no cows in the fields despite the cow pats, and no other people.

There is a gated door which could be opened and we went inside to a chamber; some stairs led up to another level but I did not go up there as I am scared of heights (and thought it might fall down).

It is a small, stumpy sort of building, and inside felt a little odd, people had been (recently) drinking there but it was not nice inside, my girlfriend thought it had an odd feeling. There were some beer bottles strewn around and signs of a fire. There were openings that let in some light, and the stairwell had openings letting in light also.

On the exterior, one side had signs of collapse, and ivy grew on some walls.

It is visible from the road outside of Doneraile where we drove to first from Fermoy (Co. Cork) to find it. It is signposted in Doneraile, but not strangely at the side of the road near the castle itself. We were able to locate it by looking up Kilcolman Bog on Google Maps (the castle does not appear on Google Maps and we did not have the correct O.S. Map, #73 I think).

We did not spend much time there. The day seemed to be most about the journey there, and getting there, being there seemed less important and the castle had little to occupy us.

Having a camera, as you probably would advise, was a distraction; it would perhaps have been better to take no pictures.

The nicest part of the journey was the view of the bog behind the castle, it seemed very ancient and tranquil.

Do let me know if you would like a photograph.

Arnold Thomas Fanning is a writer based in Dublin. His latest book, Mind on Fire, A Memoir of Madness and Recovery, was published in 2018 by Penguin Ireland.