This year’s Liverpool Biennial, with work by thirty-seven artists spread across twenty-six locations, was woven more extensively and more seamlessly into the fabric of the city than in any previous year. Several temporary public artworks were installed on the streets; others were to be found inside Chinese supermarkets and along a strip of soon-to-be-demolished terraced houses. At its most exciting, this work took the city’s built heritage as its point of departure, exploring questions about Liverpool’s imperial and mercantile legacy, its kitschy Chinatown as much as its neoclassical Victoriana. Particular attention was given to the city’s nineteenth-century Grecian appropriations, expressions of one of the great ‘noble’ ideals of colonial England.

Betty Woodman

The Summer House

2015

Ancient Greece at Tate Liverpool as part of Liverpool Biennial 2016

© Tate Liverpool, Roger Sinek

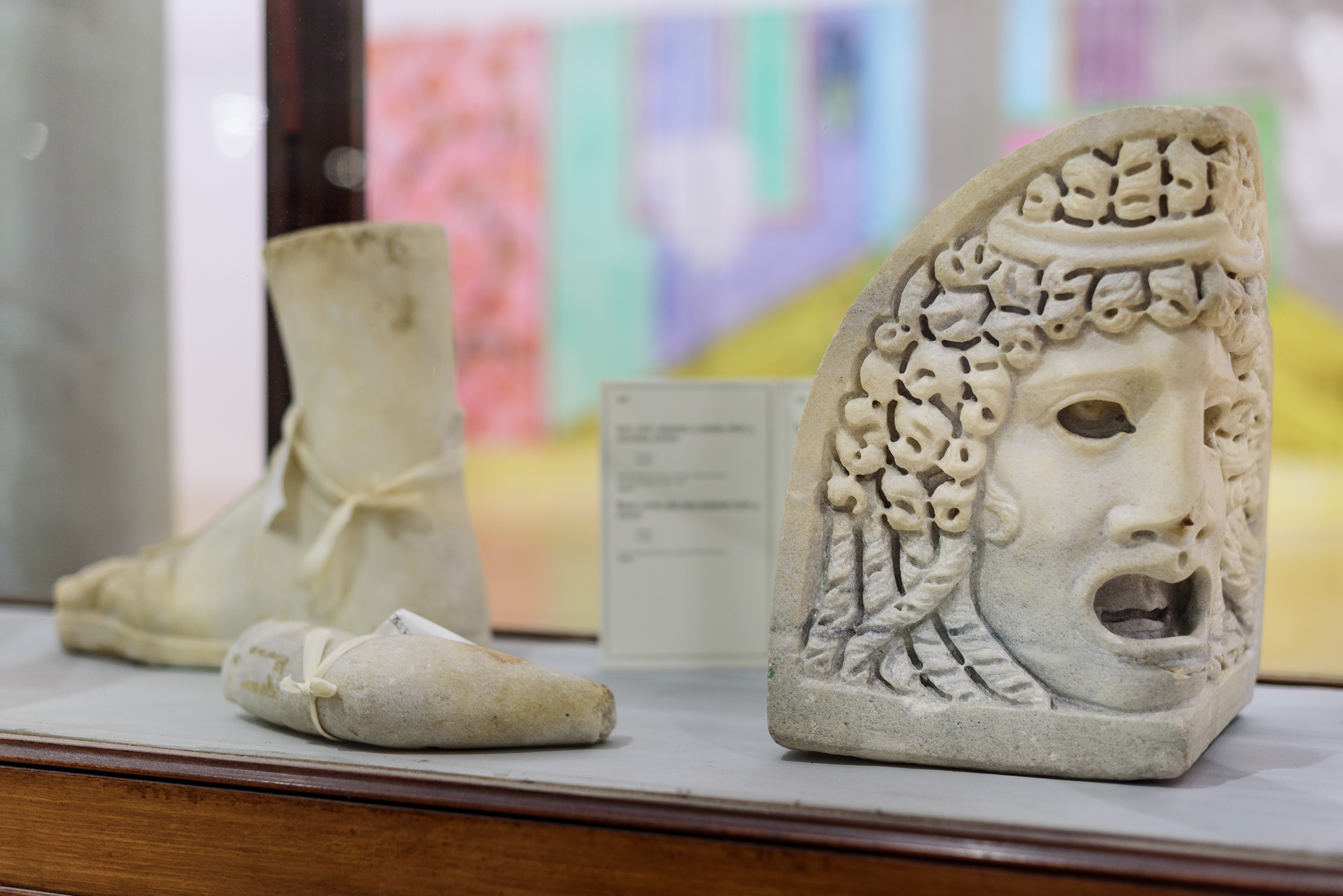

To this end, the first floor galleries of Tate Liverpool were converted into a kind of Grecian folly, featuring a selection of contemporary work surrounded by original Greek and Roman pottery and statuary (on loan from the Ince Blundell collection), all of it displayed on a decidedly nonclassical, flamingo-pink tubular display structure produced by Koenraad Dedobbeleer. Two works by ceramic artist Betty Woodman were included: Aztec Vase and Carpet 1 (2012), incorporating earthenware mosaic and bright Matisse-like colours in a piece of striking sculptural abstraction; and The Summer House (2015), an expansive, sunnily evocative mural, running along one wall of the exhibition, suffusing the room with an airy pastoral lightness. Jumana Manna’s series of sculptural works, based on research at the strikingly named Post Herbarium, in Lebanon, presented an archive of herbaceous life in the region, documenting – through the residues of agricultural and industrial activity that form the archaeological record – a genealogy of colonial exploitation. In a video work by Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian (a trio of Iranian artists), Big Rock Candy Mountain (2015), footage of the destruction of a series of monuments in Syria and Iraq is overlaid with crude, luridly coloured pencil drawings. These surging, energetically irreverent scribbles drew sprawling totemic rituals and cross-species transformations over these recordings of cultural vandalism, positing a spirit of creative anarchy as a (maybe quixotic) response to acts of devastating destruction. Taken as a whole, this room was a delight, a playfully effective collision between a number of disparate artists, connected by an interest in the transposition of classical models within the broader imperial cityscape of industrial-age Liverpool.

However, there were some exceptions to the prevailing sense of cohesion. Other works in the room seemed out of step in an otherwise integrated display, in particular Alisa Baremboym’s wavy steel sculptures, sounding a note of discord that resonated across the other venues of this year’s biennial. This discordance was the result of an unwieldy curatorial mega-structure, one which unfortunately takes some explaining. The central conceit and organising principle adopted by the eleven-strong curatorial team was that of the ‘episode’. This device was explained as a reference to Plato’s idea of ‘episodic plot’, meaning the arrangement of discrete narrative units placed one after the other. Yet the episodes of the biennial were not discrete from one another; they were intermingled, in what was referred to as an approximation of a ‘mythic’ method (also purportedly ‘episodic’), in which narrative time collapses, allowing the incursion of the mythic past into the lived present. As such, the episode served two purposes for the curators: a sequential arrangement of one-after-the-other, combined with a folding of past-into-present. [1] These two incompatible narrative tools were clumsily tied together, with predictably baffling results. The various, discrete episodes – which might have made sense as self-contained units – instead spilled out over each other, intermingling without coalescing. Hence the work displayed in Tate Liverpool related mostly to a single episode, ‘Ancient Greece’, though a few works were unrelated and seemed, as a result, confusingly misplaced. (The reductively simplistic categories only served to exacerbate an overall impression of condescension: the other episodes were called ‘Flashback’, ‘Software’, ‘China Town’, ‘Monuments from the Future’, and – most ploddingly of all – ‘Children’s Episode’.) This muddle was not made any clearer by the profusion of wall texts, over-explaining a set of conceptual threads that were even in their own right – as means of illuminating the work – unsatisfactory.

Mark Leckey

Dream English Kid, 1964 – 1999 AD (film still)

2015

Courtesy of the artist and Cabinet London

This is a shame, given the strength of much of the work at this year’s biennial spread across the city. Of these, the least cluttered venues were the most effective. In the upstairs gallery at FACT, Lucy Beech’s film work, Pharmakon (2016), was presented in rewarding isolation. Filmed on location at a number of sites around Liverpool, Pharmakon was shot with an all-female crew and cast, tracking a nightmarish shared sense of contagion – a collective terror of imagined ticks making nests in women’s skin – and an eerie ‘well-being’ cult, ‘The Healing Grapevine’, established with the promise of a cure. The result is an unnerving meditation on the interactions between environmental conditioning and bodily anxiety. Mark Leckey’s Dream English Kid, 1964–1999 AD (2015), screened at the Blade Factory at Camp and Furnace (a last-minute relocation following an arson attack on the intended site, the Saw Mill, once home to the legendary nightclub, Cream), is charged with another kind of energy, oneiric and peculiarly sexual. At its centre is a piece of found footage of a 1979 Joy Division gig, attended by the artist as a teenager in Liverpool; around this, Leckey collates snippets of TV shows, news reports, advertisements, and home footage found on YouTube, creating a disjointedly autobiographical film loop that resonates with a profound confessional honesty, its slowed-down repetitions, its nonlinguistic fixations, expressing something of the feverish anxiety of adolescence.

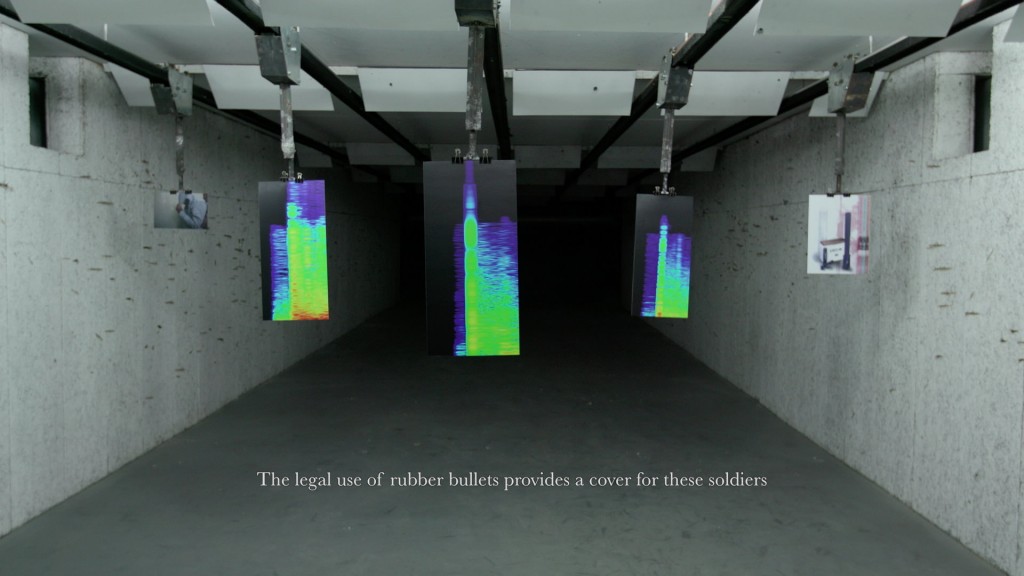

Other works gained by their presentation within vacant or semi-derelict spaces, allowing them to engage with symbolically significant, sometimes deeply evocative elements of the city’s built environment. In the neo-classical Oratory of Giles Gilbert Scott’s early twentieth century Anglican Cathedral, a video work by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Rubber Coated Steel (2016), presented the transcripts of an Israeli trial. In 2014, Abu Hamdan was asked to analyse a set of audio files related to the shooting of two Palestinian boys (Nadeem Nawara and Mohamed Abu Daher) on the West Bank. In this video work, he examines the recorded sounds of different kinds of gunshot with forensic precision, concluding that a silenced weapon had been illegally used by the Israeli military, substituting real bullets (with a rubber coating) for the legal, non-lethal variety. Abu Hamdan’s chilling lawyerly exposition of this brutal reality – presented as subtitles, without any vocals, but illustrated instead by a series of colour charts hung in a shooting gallery – gives way to an outcry from Palestinian onlookers in the courtroom, their voices from the galleries simply rendered ‘[inaudible]’ in the transcripts, a chilling representation of the ways in which silence is replicated and enforced within juridicial systems. Its situation in this venue, a choice example of Liverpool’s decorative neoclassical architecture, allowed the work to engage and resonate with its surroundings – the oratory evoking the borrowed ideals of Grecian democracy and order – prompting questions about who is served and who is silenced by such purportedly egalitarian legal systems, while at the same time activating the built environment of the city in probing, thrillingly unexpected ways.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Rubber Coated Steel (film still)

2016

Courtesy of the artist

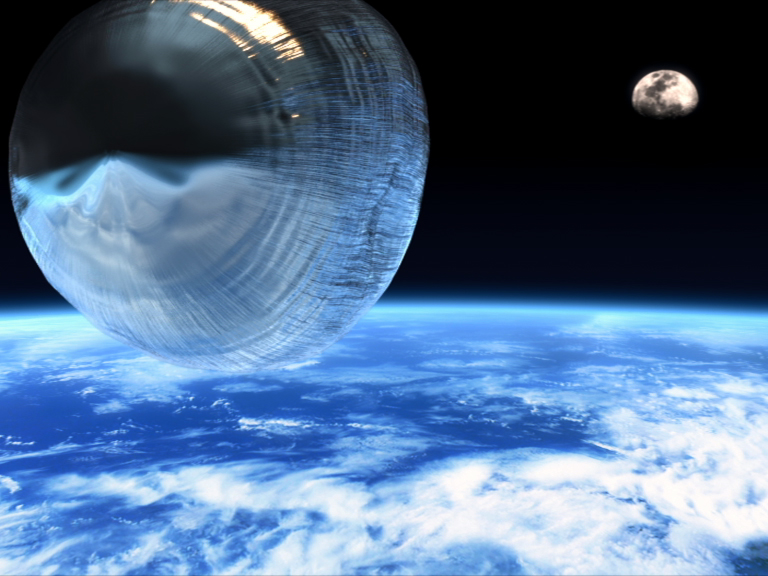

Another startling activation of the urban environment was effected in the derelict ABC Cinema, where Fabian Giraud and Raphaël Siboni’s 1922 – The Uncomputable (2016) was projected onto a huge screen. This is the latest instalment or ‘episode’ of their ongoing video series, The Unmanned, a series of works which generate phantasmagorical allegories centred upon a particular historical (or future) year, using tropes of sci-fi and horror to create dramatic parallel universes. In 1922 – The Uncomputable, the artists take as their point of departure the writings of post-war mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson, who imagined a colossal ‘forecast factory’, a vast building decorated with maps of the world, in which 64,000 workers, operating as human computers, would be able to predict the weather around the globe. Giraud and Siboni expand upon this absurdity, imagining the factory as a grandiose arena of choreographed female labour, whose ambition expands as the film proceeds, going beyond weather, taking in more and more processes to predict, a gargantuan ever-expanding set of mathematical functions that would eventually be able to predict every process on the planet, its continued operation requiring continuous labour by every person and, more, every cell on earth. This idea of permanent labour gives way to a contemplation of childbirth, concluding with an apocalyptic vision of a world destroyed by climate change, a disjointed prophetic fiction recounted by a male narrator, against strains of violent dramatic synth, while a cast of female actors battle a storm lit in lurid ultraviolet, recalling the 1980s sci-fi trash-aesthetic of films like The Running Man, though the narrative here is closer to Jorge Luis Borges’s ‘Library of Babel’. This staggering, excessive work was perfectly attuned to its environment, a crumbling Grade II listed art deco cinema, with a slanting wood floor, pitched in disorientating darkness for the running of the film, then illuminated at its conclusion, when the lights went up to reveal the ruin of the auditorium, extravagant curved decorative flourishes in blood reds and pinks, a vast, partially collapsed gold star on the roof. 1922 – The Uncomputable completely overshadowed the other works in the venue – in its wake, the scattered sculptures, almost invisible in the dark, Céline Condorelli’s black screen, and Samson Kambalu’s work, a set of short, slow, silent video clips shown across a number of screens, were difficult to take in.

Fabien Giraud and Raphaël Siboni

The Unmanned (1922 – The Uncomputable) (film still)

2016

Courtesy of the artists

Elsewhere, particularly at Cains Brewery, where a large selection of work was presented within Andreas Angelidakis’s huge circular exhibition structure, Collider (2016), the perverse effects of the episodic structure were more visible. Angelidakis’s structure itself, intended to illustrate the coming-together of the various episodes, served only to further obfuscate the work; the reference to the Large Hadron Collider at CERN felt notably hubristic. At Cains, the pitfalls of the curatorial approach were all too evident. On the one hand, naturally overlapping or dovetailing works were separated from one another; while on the other, certain works that might have benefited from a concentrated selection in a single venue, were instead filtered and adulterated across the entire show, most of them represented by a single stranded sample in the confusing abundance of the Collider. Rita McBride’s sensitive sculptural works, in particular, felt difficult to recuperate amid the clutter. In this context, the episodic framing actually detracted from the work, confusing and limiting its potential resonance. Condorelli’s Chinatown ‘portal’ was similarly misplaced, without context; part of a series of portals produced by the artist and spread across the city, one for each episode (though as no episode had a particular site, each of these portals effectively felt like a stand-alone, decontextualised work). Much more grating was the surfeit of puerile, pseudo-anarchic assemblages of non-art materials by the aforementioned trio of exiled Iranian artists, Haerizadeh, Haerizadeh, and Rahmanian: zany, purportedly ‘smuggled’ works that (in disappointing contrast to the fecund success of their video at Tate Liverpool) felt half-baked, frenetic, and intemperate.

On the other hand, Jason Dodge’s installation, What the living do (2016), pieces of everyday rubbish spread across the biennial venues, showed the potential in this model of artistic interpenetration. This gentle gesture – echoing the litter along the streets outside – provided probably the clearest signal of this biennial’s interweaving with its host city. In a similar vein, a number of buses were decorated by contributing artists and put into ongoing circulation across the city network, adding to the landscape of permanent public art (skateparks, dazzle ships), which have been the positive legacy of previous years. McBride’s startling laser installation at Toxteth Reservoir and Lara Favaretto’s granite monolith nearby, sited in the middle of a boarded-up Victorian street, were effective interventions in the broader spread of the city.

Lara Favaretto

Momentary Monument – The Stone

2016

Installation view at Welsh Streets, Liverpool Biennial 2016

Photo: Joel Chester Fildes

Another work interwoven into the urban environment was Dennis McNulty’s Homo Gestalt (2016), a three-fold set of interlinked commissions, including a digital app and a data-driven installation between the stairwells at the Bluecoat. The latter – consisting of a managerial statement pinned to the wall, a steel rigging construction, and a screen on which a severed worm writhed – felt provocative but disconnected, lacking a cohesive centre. Ancillary to this, however, a devised performance, The Time Domain, took place on the other side of the city, a promenade piece in which participants were led through a number of sites – from the neoclassical Town Hall Square to the fourth floor of a nearby unoccupied office building, and finally to the first-floor balcony of a hotel overlooking New Hall Place, or the ‘Sandcastle’ as it is known colloquially, a prominent example of 1970s Liverpool brutalism. Here two young actors, connected by headphones to a single device, enacted a piece of compact choreography, one singing, the other performing a tense, mechanical dance. McNulty’s work seemed to question the place of the human subject in the kind of managerial capitalism that made brutalism one of its public faces; but at the same time there was a suggestion as to how these relics might also now be repurposed, adapted, reclaimed. The Time Domain queried the customary understanding of top-down managerialism, suggesting instead the reliance of this kind of corporate engineering on group dynamics, individual free will, and the collaborative input of its subjects. This disjunctured, destabilising performance – something like an abstract equivalent of the immersive, site-specific theatre shows devised in recent years by Louise Lowe’s ANU Productions – seemed a necessary supplement to the installation in the Bluecoat; not resolving but rather activating and expanding upon its necessary irresolution.

Denis McNulty

Homo Gestalt – The Time Domain

Liverpool Biennial 2016

Photo: Rob Battersby

This failure or refusal to resolve seems to me a major strength of McNulty’s work. It might also be said to be the one resonating quality of the biennial overall, a quality highlighted by comparison with, say, the John Moores Painting Prize taking place at the Walker Gallery of Fine Art for the duration of the biennial. This concentrated painting exhibition, with its clear rationale (and strikingly high quality), felt controlled and transparent in stark contrast to the confused taxonomical wrangling elsewhere. Ultimately, the biennial’s curatorial framework seemed like something of a defensive exoskeleton, shielding the work, antagonising the viewer. This challenge was what resonated most vividly through the biennial: a disruptive force that ultimately felt like its redeeming feature. It is difficult to see this partial, seemingly inadvertent side effect as much vindication of the curators’ methods. Nevertheless their episodic structure did effectively preclude any critical closure – surely a positive outcome for a contemporary art biennial – making the work feel fractious, nettled, dissatisfying, and full of unsettling resonance.

Nathan O’Donnell is a writer based in Dublin.

NOTES

[1] An articulation of this dual logic is set out in the accompanying publication. See, in particular, Matthew Garnett, ‘Episodic Poetics’, in The Two-Sided Lake: Episodes, Storyboards and Sets from Liverpool Biennial 2016 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016), 26–31.