Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic.

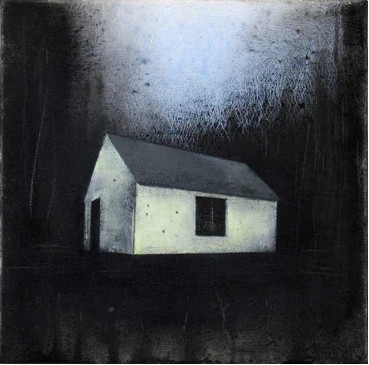

Francis Alÿs’ scribbles and doodles are playful interventions, prescriptions for a wandering mind. The miniature slabs that hang on the white washed walls, alternated with mounted texts, form a procession of playing cards. They don’t so much deal a hand as much as they offer potentials.

The work is not didactic although the texts read like instructions, and the delicate paintings of figures look like the visual accompaniment to a manual. Instead, they are more like invitations; and just like dreams, they offer a fleeting window of opportunity that is awkwardly enlightening yet somehow irrelevant and fabricated. Relevance is not it’s key concern – the act, or indeed the potential of an act, is what makes these gestures poignant.

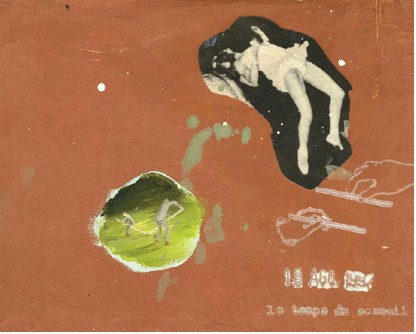

Francis Alÿs, Le Temps du Sommeil

1996 – present

series of 111 paintings (ongoing)

oil paint on wood, 11.5cm x 15.5cm

Image courtesy IMMA.

My paintings, my images, are only attempting to illustrate situations I confront, provoke or “perform” on a more public, usually urban – and ephemeral level. I’m trying to make a very clear distinction in between what will be addressing the street and what will be directed to the gallery wall. The photo residue of an act acquires a very different status (other than the act itself) once hanged on a gallery wall. It can become the finality of the piece. I tried to create painted images that could become equivalents to the action, souvenirs without literally representing the act itself. [1]

It is clear that Alÿs thoroughly considers the implications of the presentation of his work. It is also clear that, much like those involved with Land Art, what is at the heart of his work is the exercise, not the documentation. Contextualisation is inevitable, and Alÿs is not naïve enough to deny this, yet what his practice revolves around is creating individual and collective situations rather than stipulating an overarching theoretical framework.

Precedence of this concern is evident in the practice of the situationists. In his essay ‘Theory of the Dérive,’ Guy Debord quoted Chombart de Lauwe saying, “An urban neighbourhood is determined not only by geographical and economic factors, but also by the image that its inhabitants and those of other neighbourhoods have of it.”[2] Like the situationists, Alÿs hones in on these psychogeographical projections and uses them as a tool to explore narrative potentials.

Urban landscape offers much more than just its initial physical interactions; the streets, buildings and tunnels of cities allow for the construction of an elaborate network of emotional annotations and experiential attachments. The ‘feel’ of a place undoubtedly transforms once you become familiarised to its physical imposition; you shape it according to your own associations.

It is with this associative emotional behaviour that psychogeography concerns itself. Debord wrote in his ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,’ that “psychogeography sets for itself the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.’ [3]

The physical geography of an environment – which determines the aesthetic and physical limitations of a given environment – has a profound influence on the experience of the individual. This functional, architectural association, with the design of space, determines the initial response to physical surroundings. It will set a regulatory physical implication of the nature of your experience.

However, this experience is not completely predetermined by the initial physical interaction between individual and environment. Debord states that the accumalative effect of emotional response, sensory information and historical knowledge determines a personal internalisation of the environment, dependent on the individual experience as much as the physical and historical context. In ‘Theory of the Dérive,’ Debord quotes Marx to illustrate the importance of the self as a determinant for the experience of the environment: “Men can see nothing around them that is not their own image; everything speaks to them of themselves. Their very landscape is alive.” [4] Alÿs too believes that the construction of a situation is equally dependent on the environment and the interactive subject.

It is clear that Alÿs’ poetic performances have much in common with Debord’s notion of psychogeography; described as ‘a compulsive wanderer’, he himself states,

…I spend a lot of time walking around the city… The initial concept for a project often emerges during a walk. As an artist, my position is akin to that of a passer-by constantly trying to situate myself in a moving environment. My work is a succession of notes and guides. The invention of a language goes together with the invention of a city. Each of my interventions is another fragment of the story that I am inventing, of the city that I am mapping. [5]

Francis Alÿs: Study for The Last Clown

2003

animation and drawing

Image courtesy of the artist.

It is this vivacity, this elasticity of the experience that is paramount to his practice. Alÿs gives his audience a map to navigate. It is only through the interaction between his initial intervention and the audience’s reciprocation that his work comes to being. Much like a dream needs a sleeper, his prose needs an actor:

The way it happens is that , once the first scenario is set, I pass it on and watch it evolve, or die. If the concept holds, “it” will bounce back and forth (from the “other(s)” to me and vice versa), grow into something else or reinforce itself through the process of its multiple interpretation… If the concept is weak, it will have a short term live and disintegrate within the exchange process itself. It’s the test of the articulation, from an idea to a product. [6]

The potentials of the terrain are thoroughly dependent on the wanderer. Yet Alÿs’ musings are thoroughly entrenched in the terrain he walks. This situatedness, this being-in-the-world, is central to his practice. [7] In his own words, his ‘”poetical tendency” is challenged and brought back to life’s crude reality just by going down to the corner shop. No ivory tower allowed for the street will always beat your imagination…’

Yet, as André Breton aptly put it, “the imaginary is that which tends to become real,” [8] and as such, it is easy to imagine how Alÿs’ somewhat absurd propositions could be, and have been, enacted in real life.

Suzanne van der Lingen is a Fine Art Media graduate from the National College of Art and Design.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Francis Alÿs: Le Temps du Sommeil, February 26 – May 23, 2010.

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin.

[1] Romano, Gianni, (2000). ‘Francis Alÿs: streets and gallery walls’. Available at:

http://www.postmedia.net/alys/interview.htm

[2]Debord, Guy (1958). ‘Theory of the Dérive,’ p 2.

[3] Debord, Guy (1955). ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,’ p.23.

[4] Debord, Guy (1958). ‘Theory of the Dérive,’ p.3.

[5] Francis Alÿs: Le Temps du Sommeil, press release.

[6] Romano, Gianni, (2000). ‘Francis Alÿs: streets and gallery walls’. Available at:

http://www.postmedia.net/alys/interview.htm

[7] Heidegger, p.27.

[8] Debord, Guy (1955). ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,’ p.27.