French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858) once described society and the social structures within, as a “living organism.” In Northern Ireland, particularly Belfast during the peak of ‘The Troubles,’ the changing social and political situation affected the complex networks and relationships within the city. The fragmentation, segregation, dislocation and corruption of the city caused instability. These issues of corruption and decay that were, until the 1970s, romanticised or in many cases ignored by artists, have now been considered. [1]

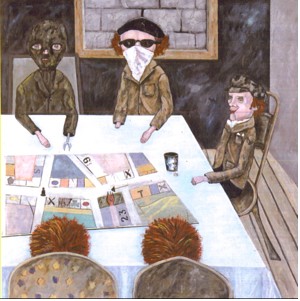

Jack Pakenham

Your Move, 1976

Jack Packenham (b.1938) and Brendan Ellis (b.1951) responded to the subject of the city and produced works which reflect the inside life. Both demonstrate the complexities contested when living in a divided, unstable society. These confessional works of everyday people are far from the motives of sectarian propagandist murals in Belfast.

By reaching beyond the archetypal media reporting and documentation, their work is best described as a social commentary on the situation at the time. As suggested by playwright Brian Mc Avera, for many artists it was easy to slide into the propaganda scope. Both artists negotiate the idea of the city as a metaphor rather than a place. [2] Their work projected the city as an extremely gripping and controversial subject.

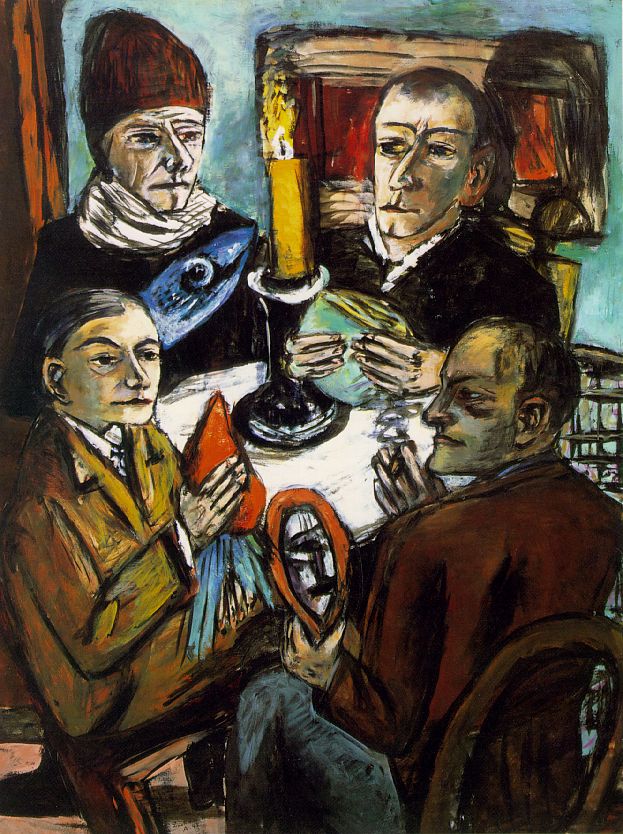

Max Beckmann

Vegetables, 1943

Packenham and Ellis hoped to challenge this dominance of corruption, decay, turbulence and fear. Correspondingly, they dealt with specific themes of city life. Using caricature styles and symbolic elements, their work was largely figurative allowing for this ‘being observed’ idea which implied alienation. Each artist’s works engages with the descriptive nature of the turmoil and war torn city, not the prescriptive reporting of it.

Dublin born Pakenham’s work can be described, largely, as expressionistic in form, with a tendancy towards the theatrical [3]. His work explores the conflict between the individual and the divided society.. He was moved by this outward and inward effect of the violence in Northern Ireland. As Steward describes, his art tends to “produce a kind of collective scream and comment that would work directly on the nervous system.” [4] Mc Avera (1990) also explains how Pakenham’s figures have built up an immunity to the “The Troubles,” and have almost become numbed – “anaesthetising themselves so that when they heard seven or eight explosions within a two-hour period they carried on” with their daily responsibilities regardless. [5]

The figures in an early work by Pakenham, Now Carefully Listen Son (c. 1976), appear unable to communicate. The subjects appear often in bleak landscapes, or alone in confined spaces. The figures are often trapped by their own suffering – his work acts like a metaphor for people caught in this civil strife. [6] In The Belfast Series (1975/6), McAvera states that the work “used the ventriloquist doll as a viciously accurate metaphor of the troubles, he found a heavy way to combine the figure within a heavily abstracted framework, the form and content went hand in hand.” [7] The doll is a motif and metaphor to reinforce the theme of manipulation. Members of such communities were without a voice, manipulated in the way in which they thought, what they felt, etc. The doll acts as a dual mechanism: branded victim, but also terrorist. Pakenham enhances the theme with a bland, seedy, and abstracted background.

The doll also reflected the plight of the artist – how he may wear a mask or pull strings or be himself, manipulated like the people who metaphorically, too become limbless. It endures tortures : tarring and feathering, hanging, or being broken.

Lastly, this idea of alienation creeps in among some of his other, less direct imagery. In order for him to portray this idea of isolation from normality, he uses vertigo in his work; often an effective technique which mirrored the vulnerability, the disillusionment of innocent citizens. As Mc Avera (1990) states “Buildings writhe, lean dizzily, fold inwards, streets become tumescent, like dank rivers, figures loom, staring out at us anxiously.”[8] This collapsed space and vertigo perspective can be seen in : Threatened Figure and Ulster at the Crossroads. They are cleverly pessimistic, with god-like viewpoints of an empty, almost deprived city life.

Ellis deals with the lack of freedom during this period of violence. Ideas of imprisonment are portrayed in a similarly expressionistic manner to that of Pakenham. Ellis’s work is extremely dynamic, with strong echoes of the German Expressionist Max Beckmann.

Ellis looked at the effect of the troubles on the victims instead of the terrorists. He “defined figures with a harsh black line and covered the surface with strong primary tones which are seemingly at variance with the darkness of the subject matter.” [9]

Ellis’s figures are gaunt, exhausted by grief and turmoil. Winos, tired mothers, hard-faced men solemnly, and without comfort, stare at the viewer – in works such as Woman on the Tenth Floor and Running Man (both c.1976). The work has a tension, with undertones of bitterness. [10] It can be said that his work was quite caricature in style. His work was not idealised or created for material consumption – it was not aiming to socially accommodate.

Art, for Ellis, had almost been adopted to give expression to the fears and anxieties of those who were not in a position to speak. The energy of the caricatures prove to be an ironic positive amidst the bleakness of the urban surroundings. By incorporating recognisable elements and symbols reminiscent of German expressionism, such as flags and emblems, (similar to that of Pakenham) his art also proved territorial and immediately explicable to the viewer.

Their work has effectively displayed the human condition during the peak of ‘The Troubles.’ With dreary hues and gloomy palettes, the expressionistic, demoralised figures within both artists’ work are successful. The oppressed subjects demonstrate the complexities contested, when living in a divided, unbalanced society.

Notes

[1] Kelly, L., (1996), Thinking Long – Contemporary Art in the North of Ireland, Gandon Editions, Kinsale, p.75.

[2] Kelly, L., (1996), Thinking Long – Contemporary Art in the North of Ireland, Gandon Editions, Kinsale, p.75.

[3] This can be seen in both his early artwork as well as the latter.

[4] Steward et al., (1999) When Time Began to Rant and Rage- Figurative Painting from Twentieth Century Ireland, Merrell Holberton, London, p. 102.

[5] Mc Avera, B. (1990) Jack Pakenham Works 75-89, Orchard Gallery, Derry, p 55.

[6] Catto, M., (1991) Art in Ulster 2 (1957-1977), Blackstaff Press, London, p.135.

[7] Mc Avera, B., (1990), Art Politics and Ireland, Open Air, Dublin, p 61.

[8] Mc Avera, B., (1990), Art Politics and Ireland, Open Air, Dublin, p 64..

[9] Mc Avera, B., (1990), Art Politics and Ireland, Open Air, Dublin, p 61.

[10] Catto, M., (1991) Art in Ulster 2 (1957-1977), Blackstaff Press, London, p.134

Amy Jackson is a graduate from Queen’s University, Belfast. She recently completed her MA in Irish Visual Culture from the University of Ulster.