Catalyst Arts was established in 1994 as an artist-run organisation inspired to some degree by Glasgow’s Transmission Gallery. The founders built a two-year transfer of power into the constitution so that the organisation’s vision, remit and output would constantly change with each new committee sworn in. This constitution was a bold move producing a list of past directors that is both long and distinguished. Many now play a central role in the wider arts infrastructure of Northern Ireland, whilst some have garnered recognition through major awards such as the Paul Hamlyn, Beck’s Futures and Turner Prize nominations.

The publicity for this visual review of the organisation identified an event from February 1996 as its point of departure, an historical story focusing on an annual members show, entitled Art Rebels. The concept : a shoe box size cardboard container was presented to Catalyst’s members to be filled decorated and appropriated by the receiver. Seventy-nine boxes were returned and exhibited anonymously. The floorboards in the gallery were lifted up and the boxes were placed between the beams to be sealed off until 2010 when they would be unearthed and reopened.

I was intrigued to see what would be revealed in these time capsules. Would the artworks have relevance or would they be bound to their time like an embarrassing music collection. I was surprised then when I entered the busy launch that no boxes were to be seen. After viewing a substantial collection of non-box artworks around the gallery spaces, I observed that the Art Rebels boxes were stacked in a backspace, like the rear of a shoe shop. Catalyst archivist, Cherie Driver, had applied a museum vault approach by secluding the contents frustratingly just out of reach. I would much have preferred to see the boxes out on public display.

The non-box works mentioned above were by over forty ex-Catalyst Arts directors. They covered a gauntlet of approaches and disciplines, some related directly to Catalyst whilst others were examples of ongoing practises. Dan Shipsides’ hand- painted Catalyst Arts sign welcomed the eye as you entered the gallery. Below, on a shelf, stood an opened nappy sprinkled with gold and glitter. The long-standing psychological connotation of faeces and gold suggests that serving on the Catalyst board may be a dualistic experience at an age when we are spurned on by naïve, youthful enthusiasm.

To the left of this was a floor and wall installation Who loves the earth? (a series of points) by Allan Hughes and Dougal McKenzie. Through the placing of different sculptural elements such as text, photographs, paintings, and a turntable, a series of complex connections are implied. There are references to Robert Smithson’s 1970 earthwork Partially Buried Woodshed that was installed at Kent University in January of that year. Four months later, the campus became a scene of student shootings by the National Guard – a notoriety overshadowing any work of art. Also referred to is Waldi, dachshund and Olympic Mascot for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. The sporting event is now remembered for the killing of Israeli competitors by the Palestinian Black September Organisation. The implication that acts of violence will always overshadow cultural initiatives seems to be a challenge rather than a nihilistic statement of inevitability.

Angela Darby / Robert Peters: Public Address ongoing….

Photographic installation

2010

Image courtesy Catalyst Arts.

Angela Darby and Robert Peters extended their ongoing project, Public Address: The People’s Wall, which documents birthday banners and posters, to create a Catalyst Arts specific piece. The spray-painted sheet announced the celebratory slogan “Happy 16th Catalyst Arts.” The artists then photographed it displayed outside buildings that have a particular significance in the history of the arts group. The photographic cartography records the building in which Catalyst was first christened, its first residence in Exchange Place, and at its present day residence in College Court. Close by, Stephen Hackett’s hilarious Operational Management of Artist Run Gallery should be distributed by the Health and Safety Executive to all artist initiated organisations. The graphic style of the presentation gives visual gravitas to the list leading you to wonder which disastrous circumstances actually happened.

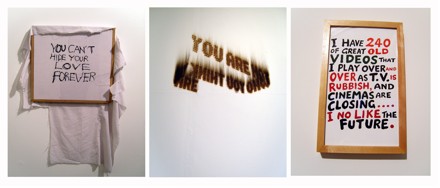

L- R : Karen Vaughan: You Can’t Hide Your Love Forever

Clive Murphy: You Are Not What you Think You Are

John Mathews ‘Hand painted road sign by ‘Moscow’ Joe McKinley

Image courtesy Catalyst Arts.

Text seems to be the preferred medium for artists from the Catalyst stable; it predominates in the exhibition. Karen Vaughan’s enigmatic slogan You Can’t Hide Your Love Forever can be interpreted as an assertive statement of truth or a declaration infused with melancholic, wishful thinking. Clive Murphy’s text, You Are Not Who You think You Are, has been burned onto the wall. A perfect combination of form and content indicates a structured deconstruction of the self. John Mathews’ photographic documentation of Hand Painted Road Sign by ‘Moscow’ Joe McKinley, Carnlough, Co. Antrim NI, 2002, records a personal statement from a man who needs to publicly share his inner life. It’s one of the most memorable works in the show, and in some way sits in the same territory as Darby and Peters’ collection of unsanctioned acts of public intervention. I wonder how ‘Moscow’ would have served as a committee member.

Ursula Burke: untitled

porcelain

2010

Image courtesy Catalyst Arts.

Ursula Burke bypasses text to interfere with religious statuettes and figurines. She applies new layers of meaning to the objects by glazing culturally significant motifs onto the ceramic surfaces, removing their original iconic identity.

Eoghan McTigue presented a photograph of the empty container in which the digital print was couriered in – a critique on the self-referential nature of art and a further development on his clever photographs of notice boards stripped of their notices.

In an adjoining room, lurked the ‘moving image’ section that included works by Mark Orange and Phil Hessian. Orange’s short, 16mm film Temps Mort: Dead Time, pays homage to a script written by the film director, Michelangelo Antonioni in the late 60s entitled Technically Sweet, that was never actually realised. By way of displaying his documentary on a small monitor, Phil Hession’s work sidestepped the pretence of technique and let his camera simply focus on artists socialising during one of Catalyst’s live events.

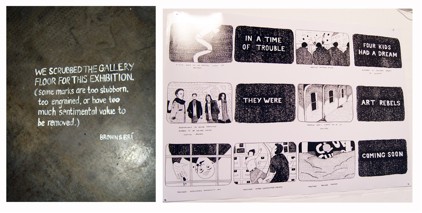

Brown & Bri: Art Rebels

2010

Fionnula Dornan: Untitled

pen on paper

2010

Images courtesy Catalyst Arts.

Brown & Bri’s simple act of sweeping and cleaning the gallery floor raises an historical question: How many times have the past and present directors swept and cleaned different Catalyst floors? At the gallery’s exit, a large comic stripe drawing by Fionnula Dornan depicts frame by frame, the beginning of the fictional Art Rebel heroes. Dornan’ s work reflects upon a time of naivety when the dream was first realised. Exhibiting alongside the very first generation of pioneering Catalyst directors makes her contribution more poignant.

Aiden Lochlin is a writer based in Derry.