On 31 January 1984, fifteen-year-old Ann Lovett left school to lie beneath a statue of the Virgin Mary in a grotto above her border town.

Is Mary your mother? My mother’s Mary. It feels like half my friends from home have a mother called Mary, and the rest have at least one Mary for a granny. Mary, the mother of us all.

Mary, my mother, was over six months pregnant when Ann Lovett pushed her baby out into a winter that killed him. Mary was moulding me from the stuff of her flesh as Ann bled to ascension.

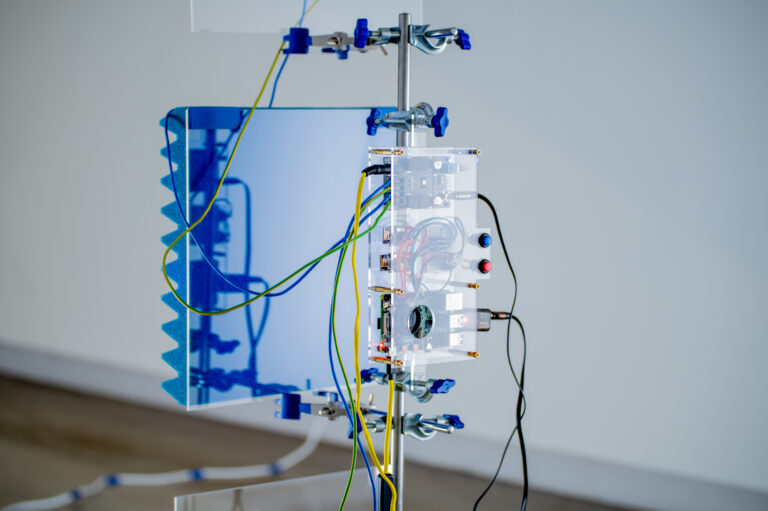

Detail of Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment banner by Alice Maher, Rachel Fallon, and Breda Mayock

2017

Photo: Alison Laredo

Ann would be forty-nine now, maybe fifty. Still young. She’d be done with bleeding, done with the years when her body could be wrest from her and declared a holy vessel. Out of danger. What would she be up to if her small town, her small nation, had not condemned her to die at the feet of an impossible ideal: virgin and mother; mother and virgin?

Would she be planning a week in the sun?

I wish Ann Lovett were turning fifty, a little overweight, one of those women with a ‘fuck yis all’ loyalty to smoking, out buying a swimsuit for Lanzarote.

I wish Mary had helped her.

The Mother of God was tired, maybe. The year 1983 had been a big one: invoked endlessly in the campaign to introduce a ‘pro-life’ (ha!) amendment to the Irish constitution; standing for hours on end as a symbol of the only appropriate reason for and response to a crisis pregnancy; being marched up and down in front of Ireland’s family planning clinics in protest of the wanton distribution of lately legal (but only with a prescription) prophylactics. She’d had a lot on.

(Besides, she was gearing up for her 1985 moving statue tour, with plans to appear at over thirty locations around the country.)

In a poem that will always be my poem for Ireland, Paula Meehan has the statue at Granard speak:

… and though she cried out to me in extremis

I did not move,

I didn’t lift a finger to help her,

I didn’t intercede with heaven,

nor whisper the charmed word in God’s ear.

Didn’t. Not couldn’t. Why? Watching a midsummer wedding, Meehan’s Mary confesses:

… I would break loose of my stony robes,

pure blue, pure white, as if they had robbed

a child’s sky for their colour. My being

cries out to be incarnate, incarnate,

maculate and tousled in a honeyed bed.[1]

Mary is a sexy Mamma. She has needs. She was practising self-care. It was ‘me time’. If she can’t have it, nobody can.

My mother (Mary, you remember) worked as a nurse for the Galway Family Planning Clinic in 1984. She still tells funny stories of the Legion of Mary parading up and down outside the premises, holding a weighty effigy of the Virgin, chanting the rosary, keeping their beady eyes out for sinners to shame. Customers would nip in as the procession passed the doorway, and then wait for it to pass back again before running off in the opposite direction with their spermicidal spoils. Larks.

The year 1984 gestated, and Mary stopped going to work because it was time to have me. On 14 April, at University College Hospital Galway, at ten past eight in the morning, I arrived. One week early. I continue to be a zealously punctual morning person. Mum says that a doctor took a picture of me as an example of a baby with perfect fat distribution. This characteristic, sadly, I failed to maintain.

On the same day, another baby was breaking the waters. A plastic bag washed up on the shore at Cahersiveen strand, Co. Kerry. In it, there was a newborn who had been stabbed twenty-eight times.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight. Nine. Ten. Eleven.

(This is upsetting to type. To type it is upsetting.)

Twelve. Thirteen. Fourteen. Fifteen. Sixteen. Seventeen. Eighteen. Nineteen. Twenty. Twenty-one. Twenty-two. Twenty-three. Twenty-four. Twenty-five. Twenty-six. Twenty-seven. Twenty-eight.

Sweet Holy Mother of Mercy.

It was known that a local woman, Joanne Hayes, had been pregnant. (I am always fascinated by the ‘it was known’ in this story: how Hayes’s pregnancy was seen and unseen; how no questions were asked until there was a corpse.)

Hayes and her family were interrogated, and, by their accounts, intimidated until they confessed to the murder of the Cahersiveen baby, a murder they did not commit. Afterwards, they produced another tiny body, Hayes’s own child, buried on the family farm. Hayes says her son died shortly after birth.

The Gardaí, not to be deprived of what Nell McCafferty designates ‘a woman to blame’,[2] ludicrously accused Hayes of conceiving twins by two separate fathers, killing one by stabbing it and throwing it in the sea and burying the other.[3]

April 1984: the cruellest month. So soon after the Irish electorate wrapped the noose of the Eighth Amendment around the republic’s womb, bodies started to push up through the earth like shoots, refusing to stay quiet in cilliní,[4] refusing to be hidden within what James M. Smith calls Ireland’s ‘architecture of containment’:[5] the Magdalene Laundries and Mother and Baby Homes designed to catch the ideological overspill of de Valera’s dewy green dreams.

Margo Harkin’s film Hush-a-Bye Baby (1990) is perhaps the most important cultural text to address this moment in Irish history. In it, our protagonist, Goretti Friel, a Derry teenager, hides a pregnancy against the backdrop of 1980s British army occupation; community devotion to both the blessed Virgin and Irish nationalism; enforced ignorance around contraception and reproduction; and a performance of modern sexual liberation influenced by cultural imports from the US.

Indebted to global feminist avant-garde film, Hush-a-Bye-Baby gradually muddies the distinction between Goretti and the Virgin. Feverish dreams confuse her pregnant body with Marian statues, until on Christmas day she goes into a nightmarish labour. Scholar Fidelma Farley astutely locates the film’s contribution to Irish national discourse in its demonstration of ‘an awareness of the pull and attraction of the fantasy maternal for women, at the same time as it deconstructs the myths that underpin that fantasy’.[6]

Mary, after all, is an unmarried teenage mother too. A small devotional figurine looks on as desperate Goretti tries to self-abort using castor oil, gin, and a scalding bath. Is the Virgin protecting her? Harkin’s film reclaims Mary somewhat from an Ireland where, to quote Farley again: ‘Issues surrounding female sexuality and reproduction are so central to ideologies of national identity that they are constantly the subject of heated debate and seemingly endless changes and revisions in legislation.’[7]

Two years after Harkin’s film came the X case, in which a supreme court judge ruled that a pregnant suicidal teenage rape victim had the right to an abortion. I was seven years old; Miss X was only seven years older. In the aftermath, the government put three referendums to the Irish people asking them, first, to remove the grounds of suicide for legal abortion, second, whether pregnant women and girls should have the right to travel for terminations, and third, whether they should have the right to access information about abortion. The electorate took a pro-choice stance on each of these issues. The government, however, did not legislate.

Instead, in 2002, it tried once again to have the people remove suicide as grounds for legal abortion. The people refused, by a hair’s breadth this time.

In 2002 I was turning eighteen, but ineligible to vote by one month. Probably a good thing. I had, after all, just spent a significant portion of my life being propagandised at Catholic school. I might even have voted to remove suicide as a ground for abortion in spite of my own pregnancy scare.

When I was sixteen, I started having (truly terrible) sex and, ergo, paid a clandestine visit to a lady doctor for the pill. I was told to wait until the first day of my period to start the prescription. But my period didn’t come. I was terrified. For weeks, I ran to the jacks between classes to check for blood.

One weekend, I managed to sneak into Galway alone to buy a pregnancy test in Boots on Shop Street (I couldn’t have bought one at the pharmacy in my village, for obvious reasons). I’ll never forget the look the woman behind the counter gave me. The Legion of Mary might not have been out marching, but it was alive and well.

I took the test on a Sunday in a public bathroom after my dance class. I was so relieved it was negative that I didn’t worry about the fact I’d become so thin that my periods had stopped.

‘You don’t look pregnant. Are you sure you don’t have cancer or something,’ says Goretti’s best friend, Deirdre.

‘I wish to God I had cancer,’ replies Goretti, not missing a beat.

A crisis pregnancy does not need to be worse than anorexia, worse than cancer.

In Áine Phillips’s landmark performance art piece Love, Sex and Death (2003), she positions abortion as a point in a cycle of female sexuality, reproduction, nurturance, and even pleasure. Milk pumps from her maternal teats. A traditional Irish fruitcake in the shape of a foetus lies in a kidney dish. Phillips chops it up and relishes a slice, offers some to her audience, invites us to chow down on a feminine ideal that tells us we shouldn’t fuck or eat.

A crisis pregnancy can be truly unterrible.

But it wasn’t unterrible for (are you ready for the oppression alphabet?): Miss C, Miss D, Miss A, B, and C (yes, there are two Miss Cs, stay with me), or Ms. Y (don’t be fooled into thinking the progressive change of honorific represents a progressive change of anything else). It wasn’t unterrible for Savita Halappanavar. Nor for Amanda Mellet or Siobhán Whelan. Nor for the family of the brain-dead woman kept alive as a slowly decomposing cadaveric incubator for an unviable foetus. Nor for the ten a day who must travel to the UK, or the five a day who take abortion pills illegally and without medical supervision.

Women must suffer for their sexuality in Ireland. But silently, you understand. We must pretend we’re off to London for a fun weekend. We must lie down at the Virgin’s feet.

Breaking this holy silence has finally placed our referendum on the table. Tara Flynn irreverently sings her abortion story in her gentle, moving one-person show, Not a Funny Word (2017). The piece burns with conviction. And, like Phillips’s foetus cake, it’s pleasurable. Grace Dyas and Emma Fraser’s powerful installation and performance art piece Not at Home (2017) uses the anonymous collected stories of women who travelled to the UK for abortions to recreate a clinic waiting room where the reading materials are Irish women’s lived experiences.

We’re praying to each other now, us girls.

Hail Mary, full of grace,

Is the Lord with thee?

No? He’s out?

Could I have a word?

I’m not doubting the whole Gabriel story and all. As a feminist, I believe women. But, you and Joseph, right? You got down. Yeah. That beard is hot.

To thee do we cry, poor banished Daughters of Eve. We’re sick of ferries and flights. We don’t want to be Ms. Z.

Mary, oh most gracious mother of us all: we know you’re on our side. Pray with us.

Notes

[1] Paula Meehan, ‘The Statue of the Virgin at Granard Speaks,’ in Mysteries of the Home (Dublin: Dedalus, 2013).

[2] Nell McCafferty, A Woman to Blame: The Kerry Babies Case (Cork: Attic Press, 1985).

[3] In January 2018 Hayes finally received an apology from the Irish state for its role in her treatment.

[4] Cilliní are burial grounds for un-baptised and stillborn babies.

[5] James M. Smith, Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries and the Nation’s Architecture Of Containment (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007).

[6] Fidelma Farley, ‘Interrogating Myths of Maternity in Irish Cinema: Margo Harkin’s “Hush-a-Bye Baby”,’ Irish University Review 29, no. 2 (1999): 220.

[7] Ibid, 219.

This text was originally published in the 38th EVA International catalogue, April 2018. Reprinted with the kind permission of EVA International.