On some of the darker days of 2016, when no glimmer of good news seemed likely, I couldn’t really care about what Ireland was supposed to be commemorating. For me at least – uncomfortable in a crowd – patriotic feeling doesn’t come easy; and the endless, maddening evidence of stark inequality and state ineptitude makes it hard to muster much flag-raising ardour. To be fair, the 1916 centenary celebrations in Ireland were sensitively pitched in soft-focus-style as occasions to ‘Remember, Reflect, Re-imagine’. Terms like ‘difference’ and ‘diversity’ were prominent in the rhetoric. And yet ‘reflecting on our achievements as a Republic in the intervening century’ [1] – one of the stated goals of the government’s programme – surely requires recognizing the egregious failures too.

A great deal of serious, original thinking about the diverse, difficult legacies of independence was done by artists during 2016: among them Jaki Irvine, whose sound-and-vision installation If the Ground Should Open …, was staged at the Irish Museum of Modern Art from September until January 2017. Through dedicated, high-profile commissioning schemes, artists such as Irvine were tasked with reflecting in fresh ways on the past, and maybe also with ‘re-imagining our future for coming generations’. [2] The resulting cultural programme was well received, inspiring a sequel. A statement introducing the follow-on Creative Ireland project notes that in 2016 ‘as we commemorated the events that led to the foundation of our state, we rediscovered the power of cultural creativity to bring communities together, and to strengthen our sense of identity’. [3] Undoubtedly, there’s merit in all this. Maybe light bulbs are now appearing over the heads of Irish politicians as they belatedly cop on to the benefits of the culture business.

Jaki Irvine

If the Ground Should Open … (detail)

2016

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Courtesy of the artist, Kerlin Gallery, and Frith Street Gallery

Nonetheless, this co-opting of the ‘creative’ can be sly. As cultural historian Robert Hewison writes of New Labour’s ‘Creative Britain’ rhetoric in the late 1990s, “Who could be against Creativity? Creative is positive and forward-looking – it is cool.” [4] Such apparently innocent, un-opposable terms seem almost the definition of ideology; New Labour’s intention was, of course, as Hewison recalls, ‘to integrate the arts and heritage into a system of government that, for all the rhetoric of a new dawn of national renewal, continued the neo-liberal programme established by the Conservatives’. [5] ‘Creative’, in these circumstances, begins to feel compromised. I wonder what would happen if – as an experiment – we were to ditch our dependence on the term ‘creative’ for a little while and replace it with ‘critical’? Instead of Creative Ireland, what would a ‘Critical Ireland’ funding scheme for new artists’ work be like? What would that shift in language mean for our understanding of art’s relation to cultural heritage or communal identity? Added to these worries about the changing implications of what ‘creative’ might mean are concerns about the patriotic expectations placed on art during and after 2016. If new creative-arts schemes aim to ‘strengthen our sense of identity’, we need to be critically vigilant too in supporting art that explores alternative possibilities – and pluralities – of coexistent identity, paying no heed to protocol, decorum, national expectation, or party line. The critical edge of the creative might help us to start new, necessary arguments: cutting through our habitual ways of thinking, separating us from what we already know, or know how to handle.

Jaki Irvine

If the Ground Should Open … (detail)

2016

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Courtesy of the artist, Kerlin Gallery, and Frith Street Gallery

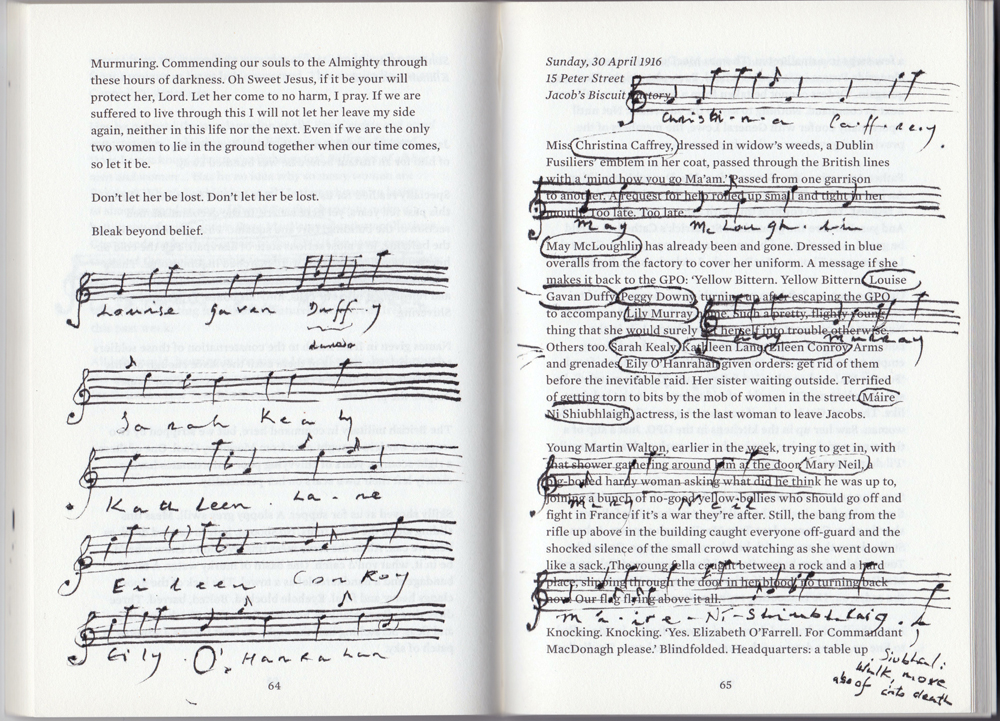

One of the first things I admired about If the Ground Should Open…, Irvine’s 1916 centenary commission, was its unapologetically blunt manner – its brusque mode of address. Throughout the homely institutional rooms of IMMA’s interlocking ground-floor galleries, Irvine positioned a series of outmoded, black, boxy monitors, each stacked on a heavy-duty flight case, with small unfussy speakers on both sides. This was a strictly functional, curatorially austere setup: no frills, no fucking about. There seemed a refusal of artistic finery: an assertion, instead of fundamental needs. This dramatically restrained display style was well suited to the seriousness of the commemorative subject matter Irvine had chosen to address. In ‘reflecting on our achievements […] in the intervening century’, Irvine had primarily focused on the role of two women – Elizabeth O’Farrell and Julia Grenan, partners for much of their lives – in the brutal struggle for an independent Ireland. Largely written out of the official, patriarchal history of Irish nationalism, along with a great many other women, the lives of O’Farrell and Grenan had been reimagined by Irvine in her 2013 novella Days of Surrender, and in this subsequent video work further tribute was paid to their revolutionary valour. (The main audio-visual installation was sparingly complemented by the inclusion of several small prints featuring annotated passages from Irvine’s book.) At one time, O’Farrell had been literally airbrushed out of historical documentation: infamously, all evidence of her presence at the scene of the 1916 Rising was removed from a photograph showing Pádraig Pearse surrendering to the British. Irvine’s clinically economical installation-style at IMMA might, then, represent a clear-sighted wish to forcefully recommunicate the importance of this history.

Jaki Irvine

If the Ground Should Open … (detail)

2016

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Courtesy of the artist, Kerlin Gallery, and Frith Street Gallery

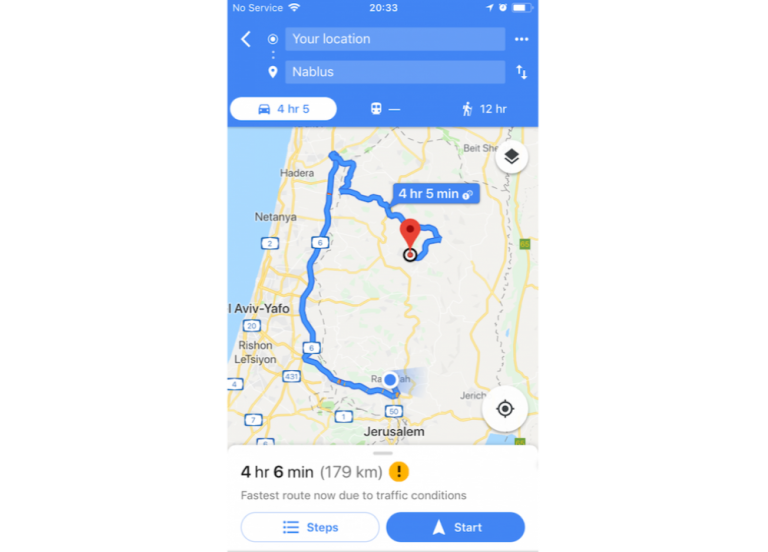

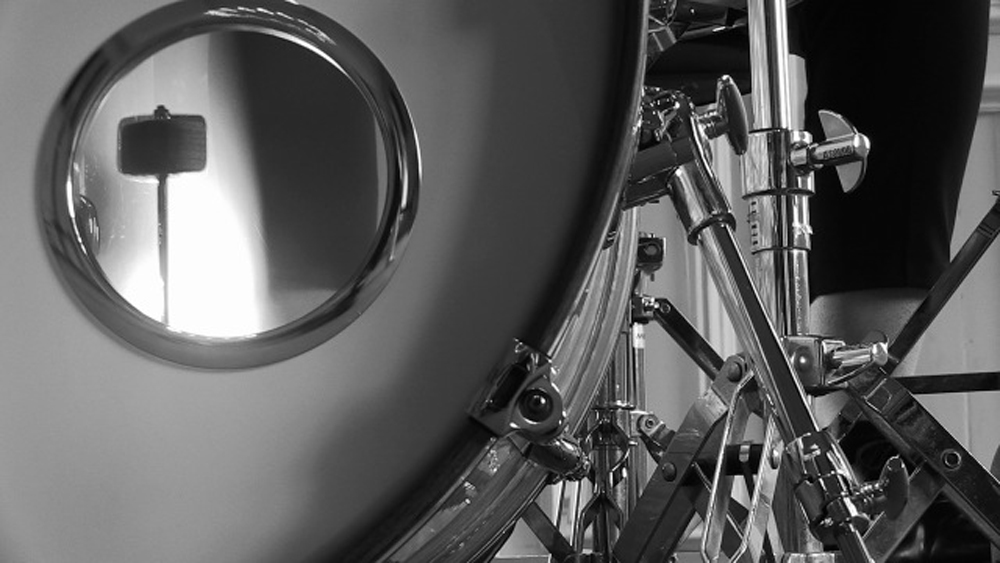

But if Irvine’s main motivation initially appeared to be about correcting the record – newly highlighting stories that deserve greater prominence within the narrative of post-colonial Ireland – the involved intricacies of her process, and of her resulting artwork, indicated a still more agitated, dissentious relationship with conventions of historical representation. The core of the project (though her final piece has really no steady centre) is a musical composition newly written by Irvine using the obscure canntaireachd system of notation: a mode of scoring originally designed for Scottish Highland pipes. In canntaireachd, chanted syllables are used as a means of recalling and communicating bagpipe melodies, and Irvine employs this practice as means of translating ‘Elizabeth O’Farrell’, ‘Julia Grenan’, and the names of other women associated with the 1916 Rising into musical sequences. The ‘ground’ of the work’s title is, in part, the musical ground created by these primary elements, but this foundation is then built upon with further elaborations, variations, and improvised adaptations. Filmed performances of the compositions come together as an often melancholy, often stirring, sonic tribute – sung and spoken vocals are variously accompanied by bagpipes, piano, violin, cello, doublebass, drums – and in each of the exhibition’s four compact rooms different passages play at different times, the camera cutting back and forth between close-ups of the various instruments or the faces of singers and speakers. This proximity to the performers invites intimacy, empathy, and solidarity – though, in truth, the music on its own didn’t entirely draw me in – but Irvine also adds rogue, purposefully distracting audio and visual components to the films that disrupt the overall mood of heartfelt solemnity. These are excerpts – sound clips and on-screen transcripts – from the Anglo Irish Bank tapes: those astonishing recordings of out-of-control banking chiefs privately revealing the depth of the coming financial crisis in 2008, and displaying contemptuous disregard for the effects of their reckless, self-serving dealings on the wider society. The honouring of one period of history is thus layered together with recent evidence of absolute dishonour.

Jaki Irvine

If the Ground Should Open …

2016

Installation view

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Photo: Denis Mortell

Courtesy of the artist

In developing this work, Irvine first wrote a book; later, this book became the inspiration for a musical score; the composition was then performed, and incrementally altered through improvisation; these performances became films, which, finally, constituted the content of a specially configured video installation. (A one-off live performance based on Irvine’s score was also held at IMMA during the show). At all stages Irvine seems to deny the authority and stability of any one approach, instead working along extending lines of ever-emergent connectivity. Each stage, in each medium, takes her to another, offering fleeting correspondences and alternate insights. It is, let’s say, a critically creative and vigilantly restless art of analogy, of perpetual movement, and of open-ended relation. Irvine’s work conscientiously recognizes the inevitable limitations and prejudices of preexisting modes of historical representation, while also fervently pursuing new means of piecing the past together, and of taking it apart.

Declan Long is a lecturer at the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, where he is course director (with Francis Halsall) of the MA Art in the Contemporary World.

If the Ground Should Open … ran from 23 September 2016 to 15 January 2017.

Notes

1. From the official ‘Ireland 2016’ website, http://www.ireland.ie/about.

2. Ibid.

3. ‘Government Foreword’ to Creative Ireland Programme 2017–2022, http://creative.ireland.ie/.

4. Robert Hewison, Cultural Capital: The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain (London: Verso, 2014), 5.

5. Ibid., 3.