Emma Haugh’s exhibition at NCAD gallery was the most recent materialisation of a project that has been running since 2013, one that has many aspects including workshops, conversations, architectural drawings, and performances. The project asks: ‘What would a space (architectural/spatial) dedicated to the manifestation of feminine desire be like?'[1] Documentation from all of these exchanges and processes is collected into a living archive, available online. Some of the archival material was displayed as part of this exhibition.

Emma Haugh

The re-appropriation of sensuality

Curated by RGKSKSRG

NCAD Gallery, Dublin, 2015

Courtesy of the artist

In the gallery space, long, meter-wide pieces of colourful fabric hung like banners. On a quiet day, it was almost like moving through an empty clothes shop; the materials were inviting: velvet, pleather, shiny poly-something. Varied in sheen and texture, these prosthetic parameters shaped the visitor’s movement through, and interaction with, the archived material. This consisted of images of displays and performances as well as material collected from workshops. One of the documents, attached to a bright yellow piece of cloth, contains descriptions of imagined all-women sex clubs and stems from one of the workshops sessions where participants were asked to describe what their idea of these sex-club spaces might be like architecturally:

This is a place where you feel like dancing.

This is a place where you feel like dancing with another woman.

This is a place where you feel like dancing with an idea, or an image, with many

or just alone. There is no crowd but just bodies in movement.

This space wants to be touched as much as the bodies inside of it.

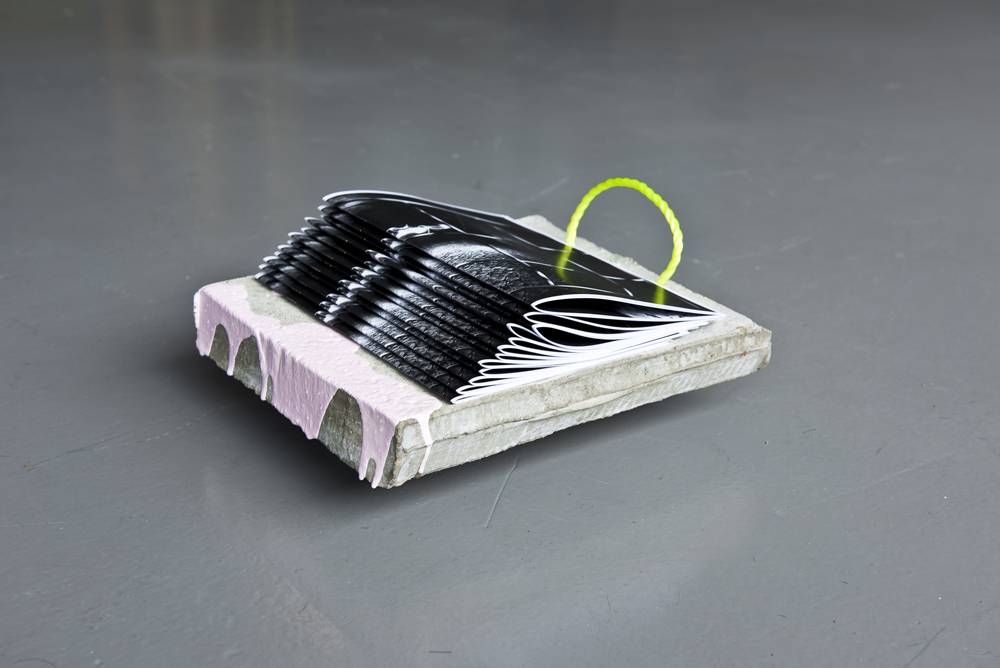

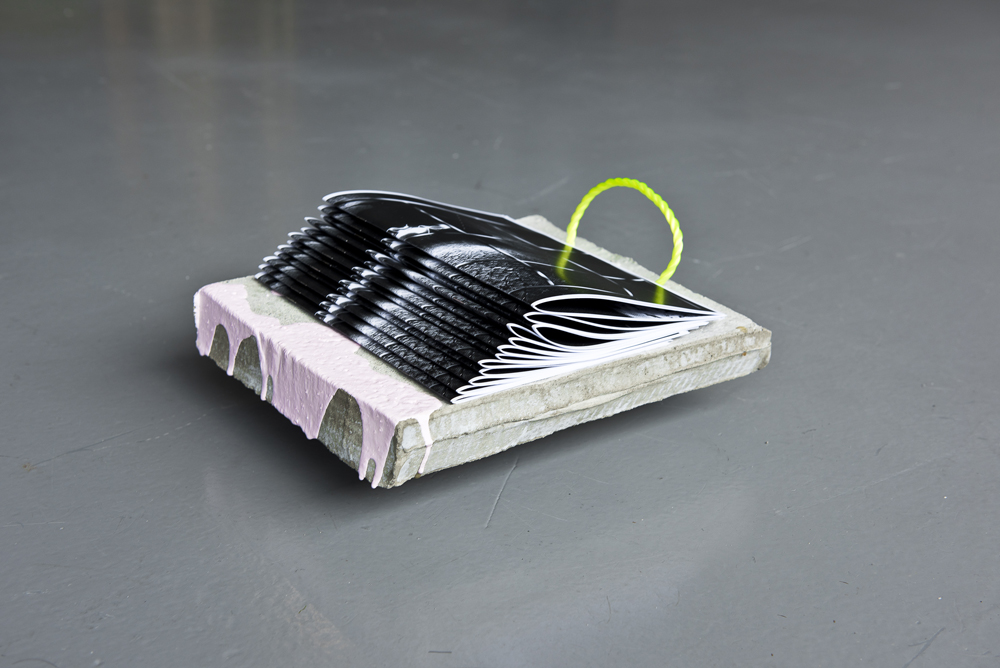

Other documents in this archive comprise renderings of these imagined spaces: remnants of exchanges the artist had with architects on this theme. Some of these documents are sleek and finished digital renderings, others are sketches in pen or pencil. Zines and posters are stacked in places, made available for visitors to take. The supports for the zines are moveable, low plinths that come up to just about ankle-level. They are made of concrete slabs, wheeled, and one has a generous dollop of pink paint sploshed on its edge. Brightly coloured string loops into a handle for one, a steel chain on another, allowing the zine-trolleys to be pulled into different positions in the space. These wheelable elements, mixed with the pivoting hanging banners, made a flexible, re-configurable frame for the exhibition. The display was not stand-offish, it was very hands-onish, maneuverable, and colourful. It flirted with its audience, danced with its audience, and part of it wanted to be taken home.

Emma Haugh

The re-appropriation of sensuality

curated by RGKSKSRG

NCAD Gallery, Dublin, 2015

Courtesy of the artist

The word ‘sensual’ can be traced back to the Latin word sensualis meaning ‘endowed with feeling’.[2] The Latin sensus means ‘feeling’, and the verb sentíre means ‘to feel’. So, to ‘re-appropriate sensuality’ would be to take up an embodied stance and re-appropriate embodiment: to sensitise. But when does what is sensed become sensual? Is the sensed always already sensual or are certain things more ‘endowed with feeling’ than others? Furthermore, when does the sensed become sexy?

In a recent essay about cause and effect and charisma in art, Timothy Morton wrote: ‘Art is charisma, pouring out of anything whatsoever, whether we humans consider it to be alive or sentient or not.’[3] Charisma is something you can’t point to, but emanates from an object/material/person. It attracts your attention, it affects you. We are affected before we make any decision about it; things act on us. For a material to be endowed with feeling it must be capable of being felt. The sensed needs to resonate through the eye, ear, or skin – it needs to speak the same language as its perceptive medium to be sensual, and to speak it well to be sexy. Is the immediacy of Haugh’s charismatic display the equivalent of something sensed becoming sexy? Charming?

*

During a workshop I attended that was hosted by Haugh, we read ‘Ornament and Crime’ (1908) by Austrian architect and architectural theoretician Adolf Loos. In it he claims (albeit over one hundred years ago) that all of art is erotic. All of art is not erotic – not all of it is even pleasant! Even gold (quite pleasant) is not erotic; it is alluring. Materials that catch our attention, objects that catch our eye, all destabilise our human position and place us within the interplay of sensory stimuli. The sheen of a material catches the light but does not glare: it is the right amount of light for our eyes and so we can rest our gaze quite comfortably. It is agreeable. It pleasantly interacts with our eyes, as an extension of them somehow.

Emma Haugh

Performance as part of The re-appropriation of sensuality

Curated by RGKSKSRG

NCAD Gallery, Dublin, 2015

Photo: Louis Haugh

In Haugh’s opening-night performance, she spoke of American writer and activist Hakim Bey’s ‘Temporary Autonomous Zone’ (1991) in relationship to the short life span of some gay bars. A hand-held projector beamed out the text Haugh recited for her performance. The light, in this instance, defined the stage, flooding across the floor, illuminating Haugh who stood in its path. The beam shook slightly. Haugh’s position also seemed unstable in its quake. Then the beam swung left, then right, and Haugh took up new positions. Re-configurable, immediate, spontaneous: this stage mirrored the zones of which she spoke, and within this, Haugh lingered on the concept of holding ground. This inconstant, ephemeral stage, though resilient because of its flexibility, demanded more of its inhabitant – quick feet, ready for relocation.

During the performance the mood shifted from playful maneuvers to malaise. Thrown, Haugh, the nomadic occupant of the projected stage became weary. Spontaneity here meant vulnerability. Unlike the sheen of the material that agrees with our eyes and allows our gaze to rest, this light was out of step with the feet it affected, the tempo too quick to be supportive.

Fiona Gannon is an artist based in Dublin.

NOTES

[1] From the artist’s website: http://www.emmahaugh.com/post/125602053626/the-re-

appropriation-of-sensuality-online-archive.

[2] As defined in the Oxford Dictionary.

[3] Timothy Morton, ‘Charisma and Causality,’ Art Review (November 2015),

http://artreview.com/features/november_2015_feature_timothy_morton_charisma_ca

usality/.

And art has an actual causal effect. Art just is tampering directly with cause and

effect, because art is what cause and effect actually is.