Recently, a woman said to me: “I just came across your website. It’s great. I like the fact that it’s curated. The quality of writing is excellent. That’s the value of curation.”

The website to which she was referring was Some Blind Alleys, the online literary journal I edit. She said she was thinking of submitting something to me – in part because I pay for contributions, but more broadly because she, like most writers, I suppose, was eager to publish her work in a place she associated with high-quality content.

While I hope she sends something, I can’t help thinking she may get a shock when she discovers that I am an editor, not a curator, and her work, if accepted for publication, will be edited, not curated. I don’t want to undersell the difficulty of curation. I must admit that my understanding of curation, in museums and galleries, is limited, and I am quite certain it is just as difficult to be an excellent curator as it is to be an excellent editor. But I do know that writers who confuse the terms are likely to be shocked by real editing. They may even consider the experience traumatic, and view edits, elisions, re-arrangements, suggestions for recasting, re-approaching, and the dozens of large-scale and small-scale queries as contrary to the idea of artistic integrity.

I have been asked by the editors of Paper Visual Art to write a brief note about my work at Some Blind Alleys, in particular how I edit, and why I edit. It’s not something I ever think too consciously about. I enjoy editing. And I enjoy the fact that readers who come to Some Blind Alleys like the content; I work with each writer to make sure he or she is happy, and that what we publish is something he or she can be proud of not just on the day of publication, but for a very long time. As a writer, I know the value of good editing, and as an editor I find the writers I admire know the value of good editing. I do, however, acknowledge that there is some confusion out there about what an editor is supposed to do, and I presume that confusion is what I’m meant to be addressing here.

I think writers who use the term “curate” to describe editing may do so as an expression of the belief that the job of an editor is to select work, clean it up for typographical errors, and publish it. This misconception arises, I think, because some authors believe that writing is a creative act whereas editing is a mechanical act. I prefer to think of the relationship between author and editor as something sacred. And on this issue I’m not speaking merely as an editor; I’m also speaking as an author who deeply appreciates the good editors with which I’ve worked.

You will, of course, find some editors who are selectors – who simply wade through slush piles, pick the best work available, suggest a vague concern here, a minor alteration there, and lay it out for publication. I suspect that the majority of literary journal editors – based on my experience with them, anyway, and based on what I hear from friends – operate in this way. One could cynically argue that it does not matter whether essays and stories in these journals are edited, since nobody reads them; that is, they exist to provide authors with publications to list on cover letters; they are, so to speak, nothing more than notches on belts.

No one, surely, starts a literary journal to publish writing that won’t be read. But if the editor is not good, or if the editor is potentially good but has not trained under (or has not gained instruction somehow from) very good editors, it does not really matter how much they want their journals to be read: they produce unreadable journals.

I have never encountered a single good author who has accused a good editor of reducing spontaneity in the author’s work, but I have heard many, many struggling writers make the broad accusation that editing – real editing, the kind that requires patience and rigor – harms spontaneity. What is this spontaneity of which the struggling writer speaks? Often it is affectation, cliché, repetitiveness, sloppiness, incoherence, and irrelevance. Authors who refuse to consider the possibility that a potentially extraordinary piece of writing may contain problems, I think, miss a real opportunity to learn something valuable about themselves. But if I told you this was generally my experience with authors – that I encounter people who are overprotective and precious – I’d be lying. I have rarely – once or twice in many years of experience, at Some Blind Alleys and elsewhere – had anything less than a profoundly positive experience with authors.

A typical response I make to an essay or story I accept for publication involves three documents. I suspect this is pretty standard stuff (it’s how my editor deals with my work, for instance). One document is a list of major queries and comments, and an explanation of my changes, cuts, etcetera (this can sometimes be made in the body of an email). Another document is one with all the changes tracked, so the author can see exactly what has happened. The third document is one with all those changes accepted, but queries left bolded. I ask the author to permit the changes I have made. Sometimes these changes – specifically I’m speaking of elisions – can be significant. If the author asks to have something re-inserted, I usually respond with a further explanation of why the cut was made in the first place; and sometimes I accept that I’ve been overzealous and re-insert according the author’s desires. I ask the author to deal with the broad queries and comments, make any changes to the document with changes accepted, and send it back to me. This process can be repeated, for a single contribution, up to four or five times. The idea is not to rush it through. The idea is to get it right.

Greg Baxter is author of A Preparation for Death, The Apartment, and Munich Airport (Penguin).

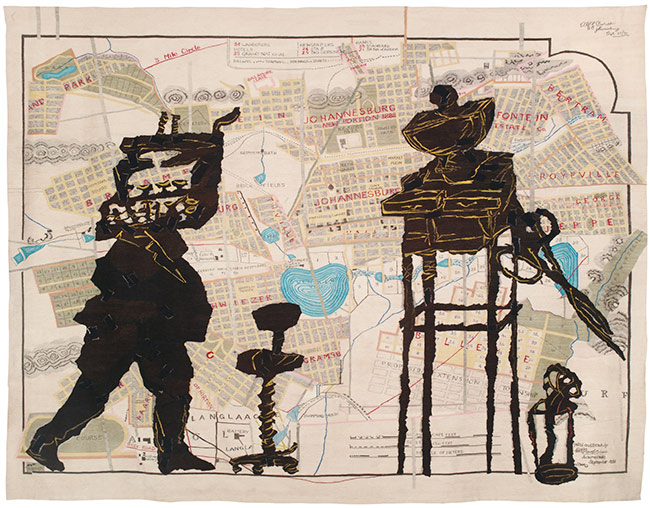

* header image – detail from William Kentridge Office Love, tapestry, 2001