Pádraic E. Moore: In April 2023, History of the Present had its debut international screening in Belfast as part of the programme to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. Co-directed by Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, this experimental opera-film explores the recent history of Northern Ireland, its defensive architecture, its sonic landscapes, using techniques and forms from both opera and experimental film to amplify stories that have been overlooked within certain narratives of conflict and post-conflict experience, particularly those of working-class women in Belfast. It has been screened nationally and internationally since, and was shown in Belfast again as part of an exhibition at the Golden Thread Gallery, with an accompanying installation of research materials, which opened in February 2025. Maria, you wrote the libretto, and you also included new compositions by Annea Lockwood and improvised vocal work by soprano Héloïse Werner. Can I ask, at what stage in the genesis of this work was opera selected as a suitable vehicle? I mean it’s moving image and it’s opera too …

Maria Fusco: I was offered a fellowship at the Royal Opera House for the initial stages of the work, which coincided with Covid. And part of the reason that fellowship happened was because I had gone to the Royal Opera House and I’d said to them, look, I think youse need to be, you know, bucking yourselves up a bit and I think you need to commission work that puts working-class voices at the fore, and luckily one of the creative directors agreed with that. And they had a fellowship called Engender, for women and non-binary creatives.

I also had it in my head that History of the Present needed to have the emotional range of an opera and the kind of pace and speed an opera can hold. And so somewhere buried within the opera-film that Margaret and I have made together is that structure – it’s quite deeply buried, but if you dig far enough you’ll find somewhat the structure of a traditional opera.

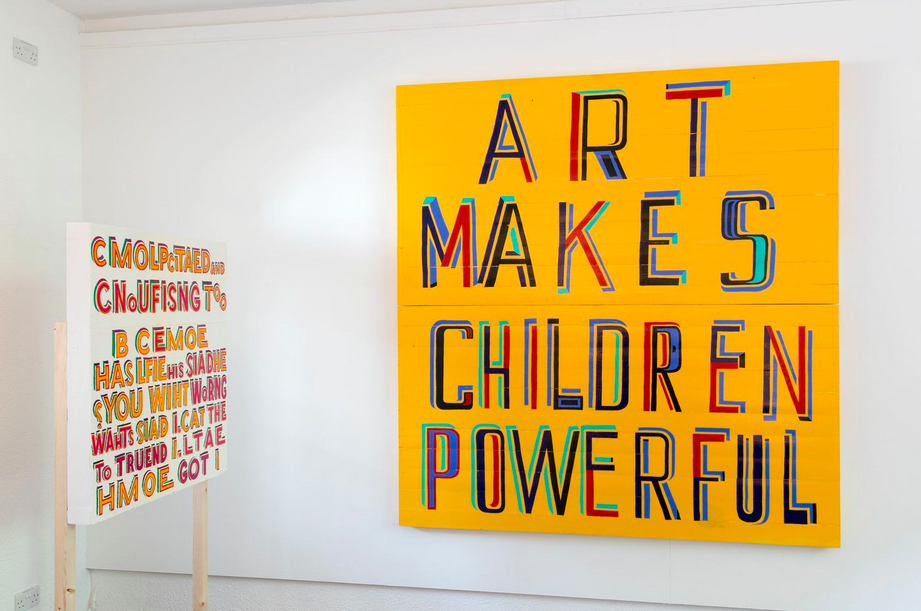

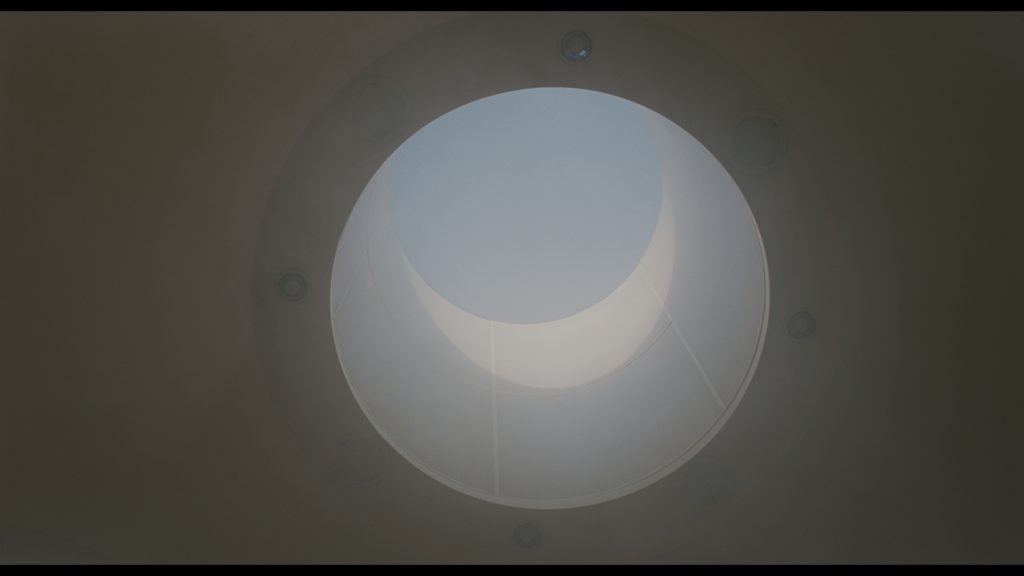

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

Margaret Salmon: When I came on board, the research had begun already and Maria had developed the libretto to some extent and had the relationship with the Royal Opera House and with Héloïse [Werner], so by then the discussion was around how to translate this through the material of film, moving image, and sound. Obviously it’s not an unthinkable thing to put together opera and film, right? There’s an interesting formal relationship and the ability to transform characters and use locations that the stage would not offer in the same way. We did quite a bit of filming in Belfast.

There was always a sense, for us, of a research process and a conversation that was live and feeding the work. We filmed in stages over the course of a year and then we ended up editing the work together and doing the sound design together. This was unusual for me in that we were able to work and then reflect and then come back again and work and reflect. And I think the film holds that process really beautifully. We were able to develop various techniques to address the topics we were discussing – regarding representation, and what might an intersectionalist feminist film be, and what is a working-class voice – all these things were integral to the process and enriched the final work.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: The form has been integral to communicating certain ideas as well as facilitating that collaborative ethos. I’m assuming that means you’re led by the other contributors to some extent, where possible, maybe not in the editing process, but their participation has found its way into the timbre of the finished work.

I wanted to comment on the score, and ask how that was developed. Héloïse’s vocal intros and exercises, through which she replicates the sounds of mechanical machines, vehicles, helicopters – you sense those things without knowing exactly what they are. So, I’m curious to know a bit about that process. Can you talk a little about Héloïse’s contribution?

MF: Héloïse is a classically trained soprano. I’ve met with a lot of trained singers during the process of devising the work. And part of what I was wondering about at the beginning was how you could score a dialect, what type of singer this should be, not in terms of whether they’re classically trained, but what voice they’re singing in. If for instance someone was originally Northern Irish, do they sing with a Northern Irish accent? And what does that mean to them?

But what became apparent was that this would mean asking a singer to revert back their voice before training, which didn’t seem desirable. So the choice was made very deliberately to work with someone who was clearly not a native English speaker. Héloïse is French. The film was very economical. Most of the takes you see, they’re just one take. So she’s improvising live with the sound. They’re not rehearsed and she wasn’t provided with the material in advance, so it’s capturing a sense of jeopardy and hesitation, an effort of her listening throughout.

The whole process with Héloïse was very intuitive, dispersed, and fragmented. Obviously she comes with a set of skills in her pocket that she’s able to use, abilities, but what’s unusual about her is her willingness to improvise. As I learned, this type of trained singing is unusual in this context, and she’s one of the only people who will do it.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: Maria, you sent me a book, the same year the work was released, Who does not envy with us is against us (Broken Sleep Books, 2023). Am I correct in thinking that strands from that book informed parts of this work? Does any of that book find its way into this film? Are there overlaps?

MF: There’s overlap in terms of the book and the film coming out at the same time – not exactly at the same time of course but in the same year. And throughout the whole process we were also making other things and, Margaret, you had other work and preparations for other work and were doing exhibitions and so forth. So in that sense, I suppose, as you know yourself, everything’s intertwined. The first essay in the book had been commissioned to run with Sean Edwards’s Welsh Pavilion at the Venice Biennale a wee while ago, and I re-drafted it. My impetus, I think, with the book was that it was quite a short, discrete thing. Margaret and I were both working on other works as well as this work at the same time, and of course teaching and of course living.

The film-making process, for very good reason, in addition to infrastructural reasons like trying to work with really big organisations such as the Royal Opera House, took a long time. And I think that some of the imagery perhaps crosses over, because it’s rooted in witnessing. But of course History of the Present is not a documentary work, it’s an experimental work. It looks at real things and it thinks about real things that have happened, but it’s not documentary in that sense so there is a kind of, I suppose, slippery relationship between different works and I guess, Margaret, this is true for yourself also …

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

MS: Yes, these forms and these methods are not set in stone, and as makers we’re still exploring: what is documentary, what is non-fiction, what is realism. This is something I do with everything I make to some extent and in this I think Maria and I share an affinity. But I was also very mindful, Maria, that we were making a work that was addressing certain experiences and histories and communities that were close to your place of birth, your upbringing, your childhood. There are actual archival voices from your family in the film.

So there is this aspect of weaving, using the materials of a kind of a reality, some sense of actuality that’s then incorporated into our imaginative collaboration. And then, applying certain technical processes of image-making and creation in film, while also playing with the notion of opera, and the emphasis or amplification that is inherent to operatic expression: all those things came together in a very detailed and particular way and I found that really exciting and super demanding … Intellectually and creatively it was quite a challenging process, balancing all these variables in one place: the final film really encapsulates that for me.

MF: Yeah it was. Because I work in an interdisciplinary way generally I never have a presupposition about form. I might have certain methods or tics, let’s say, that might be brought to bear as starting points on the work, particularly in the early stages. But if one also works alone quite a lot and then one works with a group of people towards a certain project, it creates certain interesting stresses and parameters, in a good way. I wouldn’t be able to say that work of this nature is a form of therapeutic release of a collective or personal trauma – and that’s certainly not the function of History of the Present – but there is an element of having to return in order to remember certain things in detail, to remember them as precisely as possible in order to establish an ethical, personal framework for a work of this kind.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: Some of the imagery is forensic in its description. It vacillates between quite impressionistic moments and then sharp focus. You have also have extreme moments, these almost grizzly snapshots. But I want to just to go back to something you said, Margaret, which was to do with place. There is a shot of the Divis Tower quite early on and I’d be curious to hear a little bit about the process you alluded to it at the beginning of the conversation. Did you have a handful of specific sites that needed to be present in this opera or were you drawn more intuitively to certain locations. Can you talk about the choice of locations and what that meant for you both?

MS: It was quite a thing to grapple with a place that has such an archive of representations – images, photographs, a place that has been well-documented through a particular lens and register of looking. Maria and I decided early on that we didn’t want to use any archival footage. We were more interested in asking what is in the atmosphere, what is here now, what is in the place now. I visited the city making still photographs; some of that research was shared in the exhibition at Golden Thread Gallery. Many of the pictures I took were very typical pictures of, say, the remnants or artefacts of the Troubles from a kind of outsider’s viewpoint. Later that year, I returned to the city to film. We were there twice, first documenting the field recordings and other work that Annea [Lockwood] was doing and then later with a professional crew filming various locations in the dead of winter. Over twelve months I made three extended visits to the city to try to understand what kind of visual language would be appropriate.

What I found really interesting were the ways in which we could complicate representations through the analogue materiality of the 35 mm film, using techniques such as double exposure and split screen. At one point I even put Vaseline in front of the lens and manipulated it during a take. How do you represent the unrepresentable? You know … how do you encapsulate the kind of experience of a body in a space that’s living both a past and a present at various times. So the abstract, experimental space of analogue film was for me an entrance into that consciousness or that emotional landscape. This abstraction sits alongside an inquiring camera, a surveilling camera, that’s seeking or looking for something. And it’s open to interpretation, this roaming camera. So, yes, we were aware of the historical significance of various locations. I filmed in Ardoyne, and there are recognisable places in the city centre, near City Hall for instance. But at the same time, we weren’t looking to represent a ‘wish list’ of all of the hot spots from the Troubles that everyone expects to see. That wasn’t really the impetus behind the film or the method that we used.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: Surveillance is the first thing you think of when you see these aerial shots. I suppose though, if there is a panning shot of Belfast, it’s inevitable you’re gonna see the Divis Tower. It’s one of the few totems that sticks up no matter where you’re filming from. But I was curious because it appears quite early on and is such a recognisable detail and ties into built heritage; art history and these recognisable cultural edifices. Also early on in the film you have the F. E. McWilliam sculpture, Woman in a Bomb Blast, which I found compelling. At what stage did the sculpture enter this opera?

MF: I have had a long relationship with that sculpture, as you might imagine, since I was a child, and I was curious and interested to see how Margaret would see it through a lens. Encountering it as a child was my first time seeing what I now recognise – though I didn’t at the time – to be an artistic representation of something, extreme violence, I would also have seen in reality. I wouldn’t be able to articulate that at that time, but nonetheless it was very important to me to see an artistic representation of violence, albeit very stylised and quite particular. It’s an artefact, but as something that was inside an institution, a middle-class institution in a ‘neutral’ area in Belfast, it had power, the only form actually, the only object that I had access to at that time.

I guess with its inclusion I was trying to find something not quite representative and not striving towards the representative and not striving towards the emblematic, but acknowledging that only through the combination of lots of things that may not be emblematic is meaning created.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: There’s a quote in the film about machine-pressed brick ‘hardened by history’. So the idea is that that you have to build the physical reality of things but it’s somehow permeated with – you use the word ‘trauma’ – the kind of the psychic residues that are still tangible. Not to get fetishistic about film but I suppose it too is an imprint or an index of a space or a time or a moment, so there are a lot of these resonances going on within the filming process. I’m assuming a lot of unexpected things occurred in the making of this too that were then woven into it. Do you want to talk a little bit about the unplanned element of this process?

MS: Well yes, ‘the unplanned’ – for experimental film, that’s what you’re looking for. So there are technical aspects of the work that were, yeah, just … experimental. There were also elements of documentary sound that we played with – for instance it was Maria’s idea to record our conversations during the making of the work, so we had radio mics on us while we were working in the Royal Opera House. And that sound traces some of those more spontaneous sorts of things that happen, like setting off the fire alarm in the Royal Opera House and the whole building being evacuated because of our haze machine setting off the alarms.

There was a man who I saw every time I went to Ardoyne. The first time I was in Ardoyne, I took a photograph of him and his dog who was really beautiful and then when I went back to Ardoyne I went into the local bakery and he appeared when I was giving staff prints of the photographs I’d taken of them in the previous visit. And then finally on the last days of filming in the area, he appeared again and we filmed the view from his kitchen looking onto the wall, onto the peace line, in his back garden. That’s the sort of connection that you build over time when you return to a place and you become familiar with its patterns and some of the people living there.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: There is a scene in the film where we see your other key collaborator, composer Annea Lockwood scraping a rock against a peace line, and the sound is being picked up by a contact mic, so you’re getting a resonance, a reading of the fence, and there’s a feedback loop going on between body and site …

MF: It’s interesting you should mention that now, because part of what I was reflecting on with things that are unexpected is that when you work closely with people but you sort of let them just do their own thing rather than saying, I think you need to do this/do that – like in a sense one sets up certain things, obviously, stuff like budgets and all the really boring stuff that’s also really important – but actually, working with Margaret and working with Annea, in a sense you’re working with the totality of the person, not just with what they’re able to do creatively and technically. So with someone like Annea, for example, she has a very long history of working in place and obviously being very influential over many of other people who’ve worked in places. She’s eighty-five now. So it felt really important that we could facilitate her, that we bring her to Belfast and obviously that’s quite tricky to organise but eventually, once it was done, she was able to make these sound recordings of the Ardoyne peace line, which is the one that I grew up beside, and that’s that the image that you see in the film.

Afterwards, we had a collective listening session together and then Annea went away and produced what she produced. So there is an unexpected quality to collaborating with folk when you totally trust them, because there’s no desire to control the output in a way, there’s something about the unexpected that comes along with trust actually. And also, you know, because it was post-Covid, everybody was enjoying just being together, that little part of it, even though everybody was working really hard, was a bit like fucking brilliant. Like when Margaret and I were first working together we were able to go and sit with a coffee outside, that was actually really nice you know.

PEM: Yeah I suppose when you take a form like an opera or a film it provides everyone with a placeholder that they can surrender to. It’s very evident that you have given as much free reign as was possible, to create a situation where the conditions were as open as possible to allow people creative freedom.

MS: Yeah, we were thinking about how to create a structure where everyone’s seen and listened to and supported as much as possible in a non-hierarchical way. Most of the crew were women. It was a very intimate team working on location, with the exception of the Royal Opera House, where we had their lighting crew supporting. Both Maria and I are very hands-on workers, and so were our collaborators, Héloïse and Annea. There’s an aspect of performance in all of our roles and methods – improvising and creating an open atmosphere so we can respond to what’s happening instead of forcing something to happen.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: The work coincided with, and has been framed in relation to, the twenty-five year anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. Obviously that’s something that has taken on a whole new kind of set of meanings over the course of the past few years. Can we talk a bit about this context? The notion of commemoration suggests something being finished, complete. While you can measure the fatalities, you can never really quantify the fallout from something that is still ongoing. So I’m just curious about the relationship of this artwork and the commissioning context that it came from?

MF: The work was not commissioned for the anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. But it was screened that way in Belfast as part of the anniversary in 2023. For me, showing it on the anniversary was personally significant because of my lived experience, and because of what has become possible because of the Good Friday Agreement that was not possible before the Good Friday Agreement. Written into the Good Friday Agreement is a commitment that all of the peace walls would have been removed by the time of the anniversary. In fact only a few of them have been removed, which is a vexatious thing that does open up questions for all folk who have grown up in conflict zones about what happens to what’s left behind, like the actual infrastructure of what’s left behind, what do you do with it?

So I was keen for it to be screened in this context personally, because I am from a working-class area in Belfast, and it’s still an open sore. It was important for me that a work of this nature – that is open-ended, that is experimental, that is not saying hello, here’s me a documentary, you know, that’s very, very subjective – was able to be shown in that context for the reasons that we’ve just talked about, about sensation and emotion, and how that can do a lot of intellectual work.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

Yeah, it’s a discursive work, so the drive as always, at least for me, is to create more questions than answers. And it will speak differently to different communities, in Belfast or elsewhere. When we’re thinking about the anniversaries of these histories, there’s always a question as to whose voices or whose stories have been recognised or platformed. And it’s important that working-class women’s voices and experiences are recognised and amplified within this sophisticated, complex, emotionally resonate operatic form. It felt really important to understand that a process of grieving, of recognising, of remembering, is still in play for everyone. And it was really powerful to be there in that moment with Maria when the film had its debut in the city and then to return to Belfast for the exhibition at Golden Thread the following year. I’m really curious about how it will be seen in years to come. Even though the film is finished, it’s not stable, you know, as the place is not stable … we’re not stable, nor is the history. This is also really fascinating and part of why we do it.

MF: I do think it’s really important and thanks for the question, Pádraic, because, reflecting on it, actually, it’s the form of it that’s important in the context of the Good Friday Agreement. It’s the form of it that’s the point. I strongly believe that there is space for the experimental in the mainstream, if I can put it that way, or certainly that there should be, and that we’ll have to keep chipping and pushing and pushing at that and make those demands. So specifically within the context of the Good Friday Agreement, I think it’s to do with the form – because the subject is perhaps more expected, even though, as Margaret says, the perspective is unusual, But the form is very unexpected and very unusual and opens up a very different type of possibility of discourse, for people who have been witnesses and for those who are trying to understand what that might mean for a country, and also what it might mean for future histories of conflict and colonisation and so forth.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

PEM: It’s like giving form to something that hasn’t one, or giving language or expression to something that hasn’t had it yet, isn’t it? It’s finding a new mode.

Watching History of the Present, a lot of it is not comfortable, it’s not pleasant. It feels sensorily overwhelming and this is of course magnified in the context of a darkened room with an excellent sound system. I’m curious to hear from both of you about the work’s affect and what you wanted it ‘to do’ to the viewer or the listener, the audience.

MS: We had lots of good conversations about legibility, and I think we’re both of the same mind, leaning into complexity, not making things overly palatable or easy – because, in general, they’re not, and that’s not the point of the film. So, yeah, to me, there are traditions and histories of making that we can learn from but there’s always space to understand what else is possible. We’ve talked a lot about language and voice in making the film and keep discussing it … recognising that perhaps there’s a danger in easy translation and legibility, replacing a capacity to hold complexity and not understand everything or to feel discomfort.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

MF: I agree with Margaret. At the beginning, when working with specific historical material, one needs to consider really carefully how much audiences will know about a specific moment in time and sort of, you know, obviously really take that seriously in the work. And, I mean, I suppose one thing one wants to give the audience – in whatever form it might be, however abstract it might be, however lyrical it might be – is a kind of physical sensation of disorientation, confusion. I think there are moments of that in the work. And again, I think that they come through how materials are put together, rather than a specific phrase or a specific image or a specific sound. It’s the intertwining and the interrelationships. In that sense, we are asking the audience to comprehend experientially before intellectually. My experience, sitting with audiences and speaking with folk, is that this, in a way, comes first, and then other things come afterwards.

MS: We were interested, in particular, with how sound enters the body. This was something that was really important to the work, through Maria’s performance but also Héloïse’s and Annea’s compositions. There are various ways in which they were able to speak into the body or to connect with it.

Maria Fusco and Margaret Salmon, History of the Present, 2023, film still. Courtesy the artists.

MF: When the work travels internationally, also, we have to account for the fact that complete comprehensibility is not possible. Obviously there are the archival recordings of my mother’s voice and my voice and my sisters’ voices, these thick accents that may not be understood even in England. But having shown the work internationally and having been present at some of those screenings, it doesn’t seem to be a problem for audiences because there’s this feeling in it.

I would say the experimental techniques that Margaret uses create a punctuation or punctures. When there’s the overlaying of Héloïse‘s face over the image of the city, for example, it creates a direct puncture between those two moments. So I think there is something to be said for works that are interested in creating a physical sensation that then unfolds into an intellectual realisation through the physical.

PEM: I’m sure somewhere in the vocals I can make out fragments of some aria, it might be Mozart. It sounds like the ‘Queen of the Night’ aria towards the end. I’m not sure if I’m just imagining it. Is that in there by the way?

MF: No, I think you’ve imagined that, but it’s a beautiful dream.