The following review-essay was written in response to Liz Nielsen and Max Warsh’s two-person exhibition, held at Sirius Arts Centre from 22 June to 1 August 2016 (with a further installation at Pallas Projects, Dublin, 17–27 August 2016).

Liz Nielsen and Max Warsh

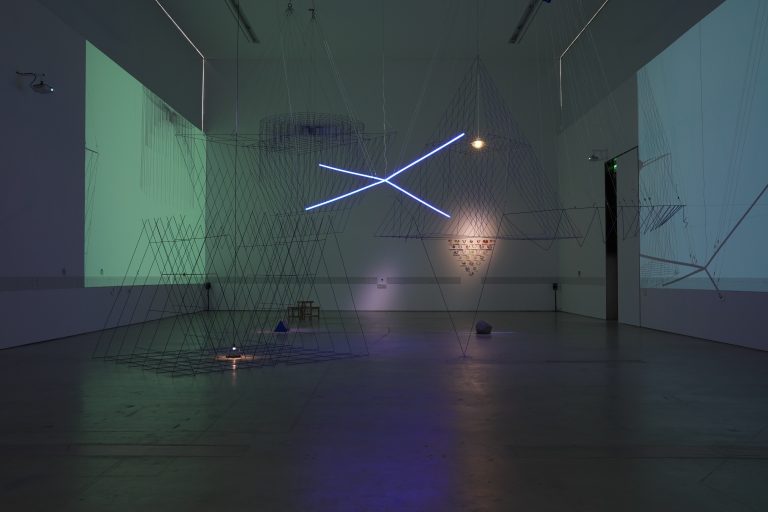

Installation view, Sirius Arts Centre

Courtesy of the artists and Sirius Arts Centre

Circles of friendship and exchange are not unusual in the art world, often, unsurprisingly, between lesser-known and younger artists and curators. And so I begin with tales of generosity. Exchange (of intellectual capital, curatorial and critical expertise, and especially of artworks) was a feature of a particular circle of friends that formed in New York in the early to mid-1960s. This included Sol LeWitt, Eva Hesse, Mel Bochner, and Robert Smithson; radiating out to include Ruth Vollmer and Dorothea Rockburne (through Bochner), and Dan Graham and Gordon Matta-Clark (through Smithson). This peer network sometimes congregated around artist Brian O’Doherty and his wife, art historian Barbara Novak, whose household provided much-needed sustenance, offering intellectual stimulation to these younger artists. O’Doherty and Novak were avid collectors, mostly acquiring through swaps, a practice in which LeWitt was also very active. The aim in both cases was encouragement and enjoyment of the work of younger artists, so these collections were always on display and were not primarily acquired for investment.

O’Doherty also had his finger on the pulse; his passion for collecting, making, and exchanging art was in tune with the thesis of his groundbreaking essay ‘Inside the White Cube: Ideologies of the Gallery Space’ (1976), which documented the emergence of an anti-institutional ethos and post-studio production values in the work of the post-minimalist generation and gave it an historical context. [1] He was involved in the visual arts as critic, funder, and broadcaster; his self-confessed ‘formidable charm’ opened many avenues for connection. His ability to communicate stemmed not only from his practice as a doctor and a writer, but more importantly, being an artist himself, he was able to speak as an equal and not as a supplicant. [2]

Something of this close knit, committed, and supportive network can often be witnessed in today’s larger art world, which is arguably even harder to negotiate. This supportive environment was certainly operative in the generation of the exhibition that showed at the Sirius Arts Centre in Cobh from 23 June to 1 August 2016. Comprising the work of two young artists from New York, the show exemplified recent interest in the materiality of photography, and celebrated the rich dialogue between abstraction, painting, film, and collage that has been building in photography throughout the last century. While Max Warsh’s works capture the play of light over the everyday urban environment of lower Manhattan, Liz Nielsen’s are created from plastic collages exposed to a variety of light sources in the darkness of her Brooklyn studio.

Max Warsh

Starr Cinema

2015

Courtesy of the artist and Sirius Arts Centre

Echoing O’Doherty’s commitment to supporting spaces such as 112 Greene Street, which showed both Bochner and Matta-Clark’s work in the early 1970s, curators Miranda Driscoll and Jessamyn Fiore both cut their teeth by running nonprofit spaces in Dublin, involving themselves in the crucial networks of spaces, people, and practices that enable new artworks to gain visibility. [3] Moreover Fiore is co-director of the Gordon Matta Clark estate; providing a direct link with that earlier circle of friends. [4]

What is useful to explore, however, beyond these echoes of friendship and support, is the interference between the two moments – the late 1960s and today – in art-historical terms. In a 2011 survey exhibition exploring Conceptual art and the photograph, Matthew Witkovski declared 1966 to be photo-conceptualism’s year zero [5]; returning to this seminal moment seems apt in examining the work of Nielsen and Warsh. Experiments begun by Bochner that year, and the work of Matta-Clark from 1968, both made conscious use of the photograph as a space of disruption. What came to interest Bochner, as Witkowski points out, ‘was the “noise” or interference introduced by photography as a form of analog capture’ [6], a concept that resonates with the subtle thematics of visual interference in Warsh’s and Nielsen’s work.

*

For the exhibition at Sirius, Warsh exhibited a series works spread across the two rooms he shared with Nielsen, varying in scale from intimate A3-sized single pieces to multiples of images each up to three times that size. These systematically collaged photographs of building surfaces, divided and put back together to appear almost (but not quite fully) reconstituted, approximate a glitch in our quotidian visual experience. Some of his works also contain a detailed patch or two, blown up and printed digitally, resulting in a change in texture and focus, as if the focus of a camera lens has been passed over the image. Much of his work is about what we miss when looking from behind the camera, or through the screen of a phone or iPad. This fascination with detail generates desire in the viewer for what is real and unmediated, though upon closer inspection, much of the actual architectural detail and ‘texture’ in these images are always already a reproduction; a poor-man’s version of stucco or woodcarving, rendered in some other material for some quite different purpose. In this light, the details of the interior wall surfaces at Sirius came to seem foregrounded: under the white paint between the windows of the central gallery, I noticed a fragment of textured dado sitting below an isolated boss, a palimpsest of previous décor, suppressed elsewhere in the room.

Max Warsh

Mysterious Sympathy

2015

Liz Nielsen and Max Warsh, Sirius Arts Centre

Courtesy of the artist and Sirius Arts Centre

Warsh’s work revels in just this kind of detail, drawn from the streets of Lower East-Side Manhattan where he grew up. The tackiness of most of the surfaces remind one of the way that Picasso and Braque clearly relished the detail of the mass produced ‘found surfaces’ of wallpapers, newsprint, faux chair-caning and woodgrain that found their way into synthetic cubist experiments in the formative first years of the twentieth century. Warsh’s use of collage bring to mind those revolutionary moments of juxtaposition; the incongruous elements exploding and rearranging the usual and familiar categories of seeing in order to explore vision afresh.

Indeed, Warsh’s approach seems deliberately out of synch with the screen-driven crispness favoured by many contemporary artists and designers. His juxtapositions of wet photography with digital detailing actually favour the former; the ‘real’ photographic object of a print on photo sensitive paper becoming a lot more readable than its deliberately grainy digitally printed equivalent. They engage the viewer at different intensities, requiring the kind of forward and backward movement usually reserved for looking at the surfaces of paintings. He explained to me that his main influence came not from fine art, but from film. The subtle cuts he makes into, across and between single prints within a particular work are informed by the construction processes of film-making. We can also read his works as a series; an accumulation of the city taken in on the hoof, or on a drive-by in a car. The visionary work of Nathaniel Dorsky was a particular influence, as were works such as Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight from 1963 and Terrence Malick’s 2011 The Tree of Life in which attention to the texture of the natural world is turned into a poetics. Brakhage enables us to become moth in his short flickering camera-less film and Warsh is likewise taken with the potential for the materiality of the photograph to directly invoke the sensations of looking: the blinks, the gaps in focus or attention or lapses of memory, needed for everyday negotiation of the world.

*

Another reference Warsh made in conversation was to Matta-Clark’s 1969 work Photo Fry, when he cooked polaroids of Christmas trees in vegetable oil and then sent them out as greetings cards. Pamela Lee writes: ‘In late 1969, a small beige package, no bigger than a cigar box, arrived at the Smithson/Holt loft on Greenwich Street. [. . .] The upper half of the box bore a virtually illegible piece of a Christmas tree, a Polaroid whose cracked and welted surface took on the appearance of charred skin. Its excrescent finish served to distort and nearly efface the image, so much so that its photographic properties were rendered irrelevant in considering the object.’ [7] Warsh’s collages are less destructive of the photographic object than Matta-Clark’s piece. In Nielsen’s work however the physical origins of her final images are not disclosed. Like Matta-Clark’s work there is a kind of alchemy involved. Also deeply engaged with the photograph as object and with camera-less image production, her process might be summarized as dancing in the dark. In order to produce her large gem-like prints – the prismatic colours glowing out from the black ground she favours – Nielsen literally performs a rehearsed ritual in the darkroom, subjecting the large sheets of photographic paper to a complex scheme of exposures using a variety of light sources from bike lamps to lasers. Between the flashes the darkness has to be complete however, and so Nielsen has to rely on memory and touch to fulfill her lengthy programme. When talking to her of this risky and often serendipitous process, I was almost as transported with the idea of her creeping around in the dark as by the resulting prints. I began to see her work as a kind of frozen firework display. The fact that these pyromaniac tendencies were only just under control somehow added to the beauty of the results. Nielsen’s work requires formidable planning and control, deploying her brightly coloured plastic collages with explosive results.

Liz Nielsen

Space Totem

2015

Courtesy of the artist and Sirius Arts Centre

These large-scale coloured compositions have an abstract purity that is reminiscent of the Bauhaus tradition, which brought a similar heady mix of experimentation and control to America, specifically through the practice and teaching of Joseph Albers. Nielsen herself describes her work as painting with light, and so perhaps, under the luminous spring skies of Cork harbour, it is unsurprising that my mind zoomed upstream to the jewel-like totemic compositions of Harry Clark’s stained glass windows that glow in the Honan Chapel at University College Cork. The similar piling of elements up a vertical axis, seen in several of Nielsen’s works, also remind us of the particular riverscape where they were made. The night view of Manhattan’s winking and blinking towers across the East River, from Brooklyn is as iconic as it is clichéd, but somehow the fact that Nielsen has reproduced something quite like it in her darkroom nearby, has a certain resonance.

And yet the whole point of her imagery is that it is not referential. Here another cycle of influence might be suggested. Returning once again to the moment of photography degree zero, to the year just before Matta-Clark fried his polaroids, in 1968 Bochner was already experimenting with colour photography. Very much against the grain, Bochner was making abstract images of shaving foam and Vaseline smeared onto glass and photographed using a series of different coloured lights. These works, Transparent and Opaque, critiqued abstract expressionism, nodded to Dan Flavin’s recent use of coloured light, and tested the limits of photography’s illusionism. As with Nielsen’s work, we cannot pin down what we are seeing even though we understand, from the indexical nature of wet photography and photograms respectively, that they originate from something objective in the real world.

Liz Nielsen

Light Totem x 2

2016

Courtesy of the artist and Sirius Arts Centre

Bochner, like Matta-Clark, experimented with photographs as objects, and with techniques that distanced these from the lens-based illusionism of most photography at that time. A case in point would be the large, enigmatic object titled Surface Dis/Tension 1968, which underwent a complicated process of facture, starting with a photocopy of a photograph of a grid. The photocopy was crumpled and re-photographed; the resulting print then peeled off the paper backing and hung up to dry before being re-photographed again. Eventually he exhibited a large blown-up print in black-and-white of a surface that appears like a crumpled handkerchief, defying all the rules of both photography and, more importantly, painting – the flatness and the framing edge being deliberately challenged here. As Bochner says, he wanted them ‘in the space of painting’ but at the same time he was interested in defying the logic of painting: ‘It just was obvious to me why does a visual object have to be a painting. A stain painting, or a stripe painting, or anything? Where is it written?’ [8] Nielsen inherits this position, from which stemmed a whole recalibration of the relationship between painting and photography, leaving behind any trace of the Greenbergian categories of medium. Rosalind Krauss has described the photograph as exemplary of the post-medium condition, and certainly here Nielsen inherits Bochner’s insistence that a photograph or a painting need not be entirely bound by conventions of technique, let alone medium. Nielsen describes her process as painting with light, and like Bochner’s strange hybrid objects, these images scintillate and wink with knowing disregard of any formal categories.

*

Late on the Friday before the show went up, I joined the artists and curators for tea and cake around the solid oak table of the basement apartment reserved for visiting artists at Sirius. As the light faded, we shared a plate of delicious tarts – hazelnut and chocolate, pear and almond – from the English Market. The firelight from the range grew and the conversation flowed. We touched on the subject of scintillation; those deliberate perceptual interferences which link the work of the two artists. It was established that several of us had experienced pain-free migraine lights, and this common experience of what is officially called Scintillating Scotoma led us to discuss our recently shared encounter with Nielsen’s works, still glowing above our heads in the now dark galleries.

Max Warsh

Highland Spring

2015

Courtesy of the artist and Sirius Arts Centre

The productive ties of friendship that developed around O’Doherty in ’68 were echoed in this more recent instance of conviviality, demonstrating the function of friendship in the building of working relationships. Like O’Doherty, Fiore has also been involved in literary circles, which brought her to Ireland originally [9], where she stayed to study for an MA and met Driscoll, whose training was in fine art photography at Falmouth in the United Kingdom. [10] Warsh and Fiore bonded at Sarah Lawrence College, in New York, over a shared interest in Matta-Clark and the 1970s [11]; Warsh also cofounded a collaborative space in New York City. [12] Nielsen and Fiore both worked for David Zwirner Gallery, in New York, while Warsh and Nielsen met in Chicago, where they both took their MFAs at the University of Illinois. This intricate history demonstrates, not only how important these ties and shared passions can be as formative moments in individual careers, but also more broadly, how these often invisible and informal exchanges still run like hidden currents beneath the surface, energising the contemporary art world.

Lucy Dawe Lane is a lecturer in contemporary art and theory at the Crawford College of Art and Design, Cork.

NOTES

[1] First published in Artforum in 1976 as a series of three essays, it was then published in book form by the University of California Press in 1986.

[2] O’Doherty and Novak, interview with the author, June 2012, Glucksman Gallery, UCC, Cork.

[3] Driscoll, who is currently the curator of Sirius Arts Centre, was cofounder, with Feargal Ward, of the nonprofit gallery space the Joinery in 2007, which was originally used as a joinery / workshop on Arbour Hill in Stonybatter. The programme encompassed gallery/project/performance spaces and small studio/workspaces: http://thejoineryarchive.org/about. Fiore was the director of Thisisnotashop, a nonprofit gallery space in Dublin from 2007 to 2010. In addition to running the space, she curated exhibitions for the space, including Gordon Matta-Clark FOOD (December 2007), Fluxus with Larry Miller (May 2009), and two Thisisnotashop exhibitions for No Soul for Sale: A Festival of Independents, held at X-Initiative in New York City (June 2009) and the Tate Modern (May 2010): http://jessamynfiore.com/?p=111.

[4] Fiore is codirector of the Gordon Matta-Clark Estate with her mother, filmmaker Jane Crawford, who is his widow. Her father, Robert Fiore, also a filmmaker, was a close friend of Matta-Clark.

[5] Matthew S. Witkovsky, ed., Light Years Conceptual Art and the Photograph 1964–1977 (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 18.

[6] Ibid., 19.

[7] Pamela Lee, Object to Be Destroyed: The Work of Gordon Matta-Clark (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 40.

[8] Edited transcript of interview with Mel Bochner in his studio 108 Franklin St, New York (16 January 2012).

[9] After graduating from Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, New York, in 2002, Fiore moved to Ireland where she ran her own theatre company for three years. The final play, SANDWICH, that she wrote has been performed in Dublin, Edinburgh, London, Prague, Czech Republic, and New York. She founded The Writing Workshop with Jessica Foley in Dublin in 2007, a collaborative forum for writers and artists who work with text. http://jessamynfiore.com/?page_id=2. There is also a New York branch. The Writing Workshop – New York City began in April 2010 and was founded by Fiore and Audrey Kobayashi: https://writingworkshopnyc.wordpress.com/about/.

[10] In 2009 Fiore received a masters in contemporary art theory, practice, and philosophy from the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, and O’Driscoll completed the same course, Art in the Contemporary World, the following year. They met subsequently through their curatorial activities (e-mail correspondence with Driscoll, 16 July 2016).

[11] Warsh’s parents were involved with running the poetry and Conceptual art publication 0-9 Magazine, which was coedited with Vito Acconci by his aunt Bernadette Mayer: http://blogs.walkerart.org/ecp/2012/09/07/bernadette-mayer-vito-acconci-and-0-to-9-magazine/.

[12] Regina Rex was founded in 2010 at the border of Ridgewood, Queens and Bushwick, Brooklyn, by Yevgeniya Baras, Jeff DeGolier, Gabe Farrar, Elizabeth Ferry, Theresa Ganz, Alyssa Gorelick, Angelina Gualdoni, Stacie Johnson, Eli Ping, Lauren Portada, Anna Schachte, Siebren Versteeg, and Max Warsh. In 2014, Rex moved to Manhattan’s Lower East Side, at 221 Maddison St: http://reginarex.org/about.asp http://www.siriusartscentre.ie/exhibitions/liz-nielsen-and-max-warsh.